Deep Reinforcement Learning: Policy-based Methods

My previous posts on reinforcement learning and value-based methods in deep reinforcement learning discussed q-learning and deep q-networks. In this post, we’re going to look at deep reinforcement methods that directly manipulate the policy. In particular, we’ll look at a few variants of policy gradients and then a state-of-the-art algorithm called proximal policy optimization (PPO), the same algorithm that defeated expert human players at DOTA.

For a more concrete understanding, i.e., code, I have a repo where I’ve implemented the DQN models and algorithms of this post in Pytorch.

Policy Gradients and REINFORCE

The value-based models that we’ve discussed a previous post use a neural network to estimate q-values which are then used to implicitly compute the policy. Consequently, these value-based methods will produce deterministic policies. In other words, the same action will be given for the same state, i.e., $a=\pi_\theta(s)$, assuming the q-values don’t change.

Recall that Markov Decision Processes could be solved with value-based methods, like value iteration, and policy-based methods, such as policy iteration. Similarly, we can directly use policy-based methods in deep reinforcement learning. This approach is called policy gradients.

For policy gradients, we use a stochastic policy $\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$, parameterized by some $\theta$, that gives us the probability of taking action $a$ in state $s$. To compute this policy, we use a neural network!

The policy network receives a game frame as input and produces a probability distribution over the actions using the softmax function. For continuous control, our policy network will produce a mean and variance value, assuming the values of our action are distributed normally.

This policy network takes in a frame from our game and produces a probability distribution over the actions (for discrete actions). Our policy network computes the stochastic policy $\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$ where $\theta$ are the neural network parameters. Anywhere you see $\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$, just think of it as the policy network.

Now that we’ve defined our policy and the role of the policy network, let’s talk about how we can train it. To improve our policy, we need a quality function to tell us how good our policy is. This policy score function is dependent on the particular environment we’re operating in, but, generally, the expected reward is a good measure of policy quality.

\[J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{(s_1, a_1,\dots, s_T, a_T)\sim\pi_\theta} \bigg[\sum_{t=1}^T r(s_t, a_t)\bigg]\](There’s a discounting factor $\gamma$ that’s supposed to be inside the expectation, but I’m going to ignore it for a while since it’ll just clutter up the derivation. I’ll add it back in later!)

In other words, the score of a policy $\pi_\theta$ is the expectation of the total reward for a sequence of states and actions under that policy, i.e., the states and actions sampled from the policy. We’ll want to maximize this function because we want to achieve the maximum expected total reward under some policy $\pi_\theta$.

For conciseness, we denote $r(\tau)=\sum_{t=1}^T r(s_t, a_t)$ and call $\tau=(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T)$ the trajectory. In practice, we can either keep taking actions until the game itself terminates (infinite horizon) or we can set a maximum number of steps (finite horizon).

Substituting $r(\tau)$ into our expectation, we get the following policy quality function.

\[J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)} [r(\tau)]\]Intuitively, maximizing this function increases the likelihoods of good actions and decreases the likelihood of bad actions, based on the trajectories of the episodes.

Trajectories are lines on the state-action space where the ellipses denote different regions of rewards. (A darker shade means a higher reward.) We want to maximize the trajectories that lead to high expected rewards and decrease the likelihood of trajectories that lead to low expected rewards.

The fact that we wrote the policy quality function as an expectation is very important: we can use Monte Carlo methods to estimate the value! In this particular application of Monte Carlo estimation, we take many samples of states and actions from the policy and average the total reward to approximate the expectation. (Whenever you see “Monte Carlo methods”, just think of it as counting-and-dividing.)

\[J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)} \bigg[\sum_{t=1}^T r(s_t, a_t)\bigg]\approx \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N\sum_{t=1}^T r(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)})\]Now that we have a policy quality function we want to maximize, it’s time to take the gradient!

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \nabla_\theta\mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)} [r(\tau)]\]We can expand the expectation into an integral using the definition of expectation for a continuous variable $\tau$.

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \nabla_\theta\int \underbrace{\pi_\theta(\tau)}_\text{probability} \underbrace{r(\tau)}_{\substack{\text{random} \\ \text{variable}}} \mathrm{d}\tau\]Then, we can move the gradient operator into the integral since we’re taking the gradient with respect to the parameters $\theta$, not the trajectory $\tau$.

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \int \nabla_\theta\pi_\theta(\tau) r(\tau) \mathrm{d}\tau\]We need to convert this equation back into an expectation somehow so we can use Monte Carlo estimation to approximate it. Fortunately, we can use the following logarithm identity (read backwards) to accomplish this.

\[f(x) \nabla \log f(x) = f(x)\frac{\nabla f(x)}{f(x)} = \nabla f(x)\]Now we just replace $f(x)$ with $\pi_\theta(\tau)$ and use the identity.

\[\int \nabla_\theta\pi_\theta(\tau) r(\tau) \mathrm{d}\tau=\int \pi_\theta(\tau)\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(\tau) r(\tau) \mathrm{d}\tau\]Now we can convert this back into an expectation!

\[\int \underbrace{\pi_\theta(\tau)}_\text{probability} \underbrace{\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(\tau) r(\tau)}_\text{random variable} \mathrm{d}\tau = \mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)} [\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(\tau)r(\tau)]\]This gives us the gradient of our policy quality function!

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)} [\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(\tau)r(\tau)]\]The last thing that remains is applying the gradient to $\log\pi_\theta(\tau)$ so that we can write $\nabla_\theta J(\theta)$ in terms of $\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$, i.e., our policy network! Taking the gradient of this just means using backpropagation on our policy network!

According to our notation substitution, we can replace $\tau$ with $(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T)$

\[\pi_\theta(\tau) = \pi_\theta(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T)\]Now we need to write $\pi_\theta(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T)$ in terms of $\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$. Intuitively, $\pi_\theta(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T)$ represents the likelihood of this trajectory so we can expand it using probability theory.

\[\pi_\theta(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T) = p(s_1)\prod_{t=1}^T\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)p(s_{t+1}\vert s_t, a_t)\]In words, we’re expanding the probability of observing a particular trajectory $s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T$. The first term is the probability of the starting state $s_1$. The product operator computes the overall probability of all of the transitions. To transition to a new state $s_{t+1}$, we need to take an action in the current state, but, since our policy is stochastic instead of deterministic, we use the policy $\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)$ to give us the probability of taking action $a_t$. Now that we have a representation of the action, we can use the transition function $p(s_{t+1}\vert s_t, a_t)$ to compute the probability of the next state. Combining all of these together, we get the overall probability of observing the trajectory.

For numerical stability, i.e., to prevent underflow, we take the logarithm of both sides, and multiplication becomes log addition.

\[\log\pi_\theta(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T) = \log p(s_1)+\sum_{t=1}^T\bigg[\log\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)+\log p(s_{t+1}\vert s_t, a_t)\bigg]\]Finally, we can take the gradient of both sides. Notice that the first and last terms on the right-hand side are not a function of $\theta$ so they can be removed.

\[\require{cancel}\] \[\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T) = \nabla_\theta\bigg(\cancel{\log p(s_1)}+\sum_{t=1}^T\bigg[\log\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)+\cancel{\log p(s_{t+1}\vert s_t, a_t)}\bigg]\bigg)\]Then we can move the gradient operator inside of the sum, and we’re left with the following.

\[\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T) = \sum_{t=1}^T\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)\]Notice that we’ve effectively arrived at a maximum likelihood estimate using log likelihoods! This is because $\pi_\theta(s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T)$ just computes the likelihood of the trajectory $s_1, a_1, \dots, s_T, a_T$.

Now we’ve represented $\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(\tau)$ in terms of $\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)$ and we can finish writing the full policy gradient! Recall the gradient of $J(\theta)$.

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)} [\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(\tau)r(\tau)]\]Fully expanded, we arrive at the following.

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)}\bigg[ \bigg( \sum_{t=1}^T\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t) \bigg) \bigg( \sum_{t=1}^T r(s_t, a_t) \bigg) \bigg]\]Let me take a second and explain this intuitively in its two sums.

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)}\bigg[ \underbrace{\bigg( \sum_{t=1}^T\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t) \bigg)}_{\text{maximum log likelihood}} \underbrace{\bigg( \sum_{t=1}^T r(s_t, a_t) \bigg)}_{\text{reward for this episode}} \bigg]\]By multiplying the likelihood of a trajectory with its reward, we encourage our agent to increase the probability of a good trajectory if the reward is high, and, discourage it if the reward is low.

One other thing we can fold in is the discount factor $\gamma$. We need to discount rewards backwards in time, similar to computing the value of a state.

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)}\bigg[ \bigg( \sum_{t=1}^T\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t) \bigg) \bigg( \sum_{t=1}^T \gamma^{t-1} r(s_t, a_t) \bigg) \bigg]\]Now that we have the gradient of the quality function, we can write the algorithm, called the REINFORCE algorithm, to maximize this function and train our policy network!

-

Sample a trajectory ${\tau^{(i)}}$ from $\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$. In other words, run the policy and record the values of the reward function $r(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)})$ and log probabilities $\log\pi_\theta(a_t^{(i)}\vert s_t^{(i)})$.

-

Compute the policy gradient by averaging across the trajectory. $\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N}\sum_i\bigg[ \bigg( \sum_t\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(a_t^{(i)}\vert s_t^{(i)}) \bigg) \bigg( \sum_t \gamma^{t-1} r(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)}) \bigg) \bigg]$

-

Update the parameters (where $\alpha$ is the learning rate). $\theta\gets\theta + \alpha\nabla_\theta J(\theta)$

(Notice that we’re using gradient ascent instead of descent here since the goal is to maximize our score function!)

To collect training data, we sample trajectories from our policy, i.e., run the policy network for a game, and collect the rewards. We use the rewards to compute our “ground truth” values and fit a model to them, now that we have data and “labels”. Finally, we update our model’s parameters using gradient descent.

We can draw some analogies between reinforcement learning and supervised learning. Really reinforcement learning is just like supervised learning where the training data is sampled and computed from the policy. We batch these data and train them using our policy network, just like a supervised learning algorithm. We don’t really have “ground truth” labels, so we compute them using the discounted reward.

Practical Implementation

Now that I’ve laid down the foundations of vanilla policy gradients, there are a few implementation details to actually get them working with automatic differentiation (autodiff), used in Pytorch and Tensorflow.

Going step-by-step from the original algorithm, the first thing we need to do is collect trajectories to compute the loss. Autodiff will handle computing the gradient and updating the model parameters. Notice that our loss function really just needs the log probabilities of the actions and the corresponding reward so those are the only two things we need to store when collecting trajectories.

\[J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N}\sum_i\bigg[ \bigg( \sum_t\log\underbrace{\pi_\theta(a_t^{(i)}\vert s_t^{(i)})}_{\text{from network}} \bigg) \bigg( \sum_t \gamma^t\underbrace{r(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)})}_{\text{from env}} \bigg) \bigg]\]Since we’re using Monte Carlo methods, we can collect these log probabilities and rewards and aggregate them by averaging. The next step is fitting the model, which autodiff can do for us if we provide it the loss value.

Additionally, we normalize, i.e., subtract the mean and divide by the standard deviation, the temporally discounted rewards to help reduce variance and increase stability. There are formal proofs that show why this works, but I’ve omitted them since they don’t add that much to the discussion and normalizing is a fairly standard practice in the community.

The final, minor point is that many optimization algorithms in software libraries are going to perform some kind of descent in our parameter space, however, we want to maximize our policy quality function. The easy fix to turn our policy quality function into a loss function is to multiply the quality by $-1$! We’ll simply sum up the negative log probabilities, scaled by the normalized rewards, and perform gradient descent on the parameters using that loss value.

A more detailed REINFORCE algorithm looks like this.

- For each episode do

- For each step do

- Sample the action $a\sim\pi_\theta(s)$ and store $\log\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$

- Execute the action $a$ to receive a reward $r$ and store it.

- If the episode is not done, skip to the next iteration.

- Compute the discounted rewards using the discount factor: $R_t = \sum_{t’=0}^t \gamma^{t’} r_{T-t’}\gets [r_T, r_T+\gamma r_{T-1}, r_T+\gamma r_{T-1}+\gamma^2 r_{T-2}, \dots]$.

- Normalize the rewards by subtracting the mean reward $\mu_R$ and dividing by the standard deviation $\sigma_R$ (and adding in an epsilon factor $\epsilon$ to prevent dividing by zero): $R_t\gets\frac{R_t-\mu_R}{\sigma_R+\epsilon}$.

- Multiply the negative log probabilities with their respective discounted rewards and sum them all up to get the loss: $L(\theta) = \sum_t -\log\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)\cdot R_t$.

- Backpropagate $L(\theta)$ through the policy network.

- Update the policy network’s parameters.

- End for

- For each step do

- End for

One advantage of policy-based methods is that they can learn stochastic policies while value-based methods can only learn deterministic policies. There are many scenarios where learning a stochastic policy is better. For example, consider the game rock-paper-scissors. A deterministic policy, e.g., playing only rock, can be easily exploited, so a stochastic policy tends to perform much better.

A related issue stochastic policies solve is called perceptual aliasing.

Perceptual aliasing is when our agent isn’t able to differentiate the best action to take in a similar-looking state. The dark grey squares are identical states in the eyes of our agent, and a deterministic agent would take the same action in both states.

Suppose our agent’s goal is to get to the treasure while avoiding the fire pits. The two dark grey states are perceptually aliased; in other words, the agent can’t differentiate the two because they both look identical. In the case of a deterministic policy, the agent would perform the same action for both of those states and never get to the treasure. The only hope is the random action selected by the epsilon-greedy exploration technique. However, a stochastic policy could move either left or right, giving it a higher likelihood of reaching the treasure.

As with Markov Decision Processes, one disadvantage of policy-based methods is that they generally take longer to converge and evaluating the policy is time-consuming. Another disadvantage is that they tend to converge to local optima rather than the global optimum.

Regardless of these pitfalls, policy gradients tend to perform better than value-based reinforcement learning agents at complex tasks. In fact, many of the advancements in reinforcement learning beating humans at complex games such as DOTA use techniques based on policy gradients as we’ll see shortly.

Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C)

Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) is a hybrid architecture that merges policy-based and value-based learning into a single approach.

As the name implies, there are two components: an actor (a policy-based agent) and a critic (a value-based agent). The actor gives us the action distribution, i.e., the stochastic policy $\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$, to select the action in the environment, and the critic tells us how good that action was, i.e., the value $V(s)$. As we train, the actor learns to take better actions from critic feedback, and the critic learns to provide better feedback.

Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) uses the same base network with two output heads: one that produces a probability distribution over the actions for the current state and the other that computes the value of that state.

A2C solves a major issue with policy gradients: we only compute the reward at the end of the horizon so we only consider the average. We could have a sequence of actions where all of our actions produced small positive rewards, except one action produced a very negative reward. Because of this averaging, the action with the awful result is effectively hidden among the actions with the better results.

Instead, A2C incrementally updates the parameters at some fixed interval during the episode. To get this working, however, our policy gradient needs some changes.

Recall our policy gradient from the previous section.

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N}\sum_i\bigg[ \bigg( \sum_t\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(a_t^{(i)}\vert s_t^{(i)}) \bigg) \bigg( \sum_t \gamma^t r(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)}) \bigg) \bigg]\]The reward function computes the reward for the entire episode. If we’re incrementally updating our parameters inside of an episode, we can no longer use the reward function here. Instead, we can replace the reward function with the q-value function.

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N}\sum_i \sum_t\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(a_t^{(i)}\vert s_t^{(i)}) Q(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)})\]Recall that the q-value tells us the expected reward for taking an action $a$ in a state $s$. This gives us a quality metric inside of the episode without having to wait for the end of the episode for the reward function. However, our critic only computes the value $V(s)$, not the q-value. But recall that there’s a relation between the q-value of a state and the value at the state: $Q(s, a) = r + \gamma V(s’)$ where $s’$ is the state we end up in after taking action $a$ in state $s$ and $r$ is the reward for taking action $a$ in state $s$.

Instead of using the q-value directly, we can go a step further using the advantage function. We learned with DDQNs that the advantage function helps improve learning by reducing variance. So instead of the q-value function, let’s use the advantage function in the policy gradient.

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N}\sum_i \sum_t\nabla_\theta\log\pi_\theta(a_t^{(i)}\vert s_t^{(i)}) A(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)})\]where $A(s, a) = Q(s, a) - V(s)$.

Intuitively, $Q(s, a)$ tells us the reward for taking action $a$ in state $s$, and $V(s)$ tells us the total reward from being in state $s$. Hence, $A(s, a)$ tells us how much better taking action $a$ in state $s$ would be. If $A(s, a) > 0$, then our action does better than the average value of the state; if $A(s, a) < 0$, then our action does worse than the average value of the state. By multiplying our policy network gradient by the advantage, we push our parameters so that good actions, i.e., actions such that $A(s, a) > 0$, more probable and bad actions, i.e., actions such that $A(s, a) < 0$, less probable.

The advantage is particularly useful when we have a state where all actions produce negative rewards. Since the advantage function computes the value relative to $V(s)$, we can still select the best possible action in that bad state. The advantage function allows us to make the best of a bad situation, so to speak.

Finally, we can write an expression for the loss of the actor head, i.e., the policy head (and notice it looks very similar to vanilla policy gradients with the exception of the advantage function).

\[L^\text{A}(\theta) = \frac{1}{N}\sum_i \sum_t\log\pi_\theta(a_t^{(i)}\vert s_t^{(i)}) A(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)})\]where

\[A(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)}) = r(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)}) + \gamma V(s_{t+1}^{(i)}) - V(s_t^{(i)})\]Now let’s look at the loss of the critic head of the actor-critic architecture. If we trained it using the same loss as the DQN, we’d need two functions: the q-value function and the value function. However, we can make an improvement by only fitting the value function $V(s)$ if we notice that the q-value, in our case, is really just a function of the reward and value functions. Since we’re already using the advantage function, we can estimate it using the temporal difference error.

\[A(s_t, a_t) = r(s_t, a_t) + \gamma V(s_{t+1}) - V(s_t)\]So our loss for the critic is simply the temporal difference error itself.

\[L^\text{C}(\theta) = \frac{1}{N}\sum_i \sum_t \mathcal{L}_1\Big( A(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)})\Big)\]where $\mathcal{L}_1$ is the Huber loss. (This is the same loss we used when discussing DQNs. Read this, specifically the section Reward Clipping and Huber Loss, if you need a refresher as to why it’s an improvement over squared error or quadratic loss.)

One final component to the A2C architecture is exploration. For DQNs, we used an epsilon-greedy approach to select our action. But with a stochastic policy, we sample from the action distribution so we can’t follow the same approach. Instead, we embed the notion of exploration into our loss function by adding an entropy penalty.

Low entropy action distributions have one action that is much more likely than the others while high entropy action distributions spread the probability nearly evenly across all actions.

The idea is that we want to penalize low entropy action distributions because this means we’re very likely to select the same action over and over again. Instead, we’d prefer lower entropy action distributions (think back to perceptual aliasing). We can compute the entropy of the action distribution using the definition of entropy:

\[S = -\sum_i P_i\log P_i\]When applying it to our action distribution, we get the following.

\[L^\text{S}(\theta) = \sum_a \pi_\theta(a\vert s)\log\pi_\theta(a\vert s)\]We’re omitting the negative sign at the beginning since we’ll be incorporating it into the combined loss function.

Now we can put all of the pieces of the loss together into one expression.

\[L(\theta) = L^\text{A}(\theta) - L^\text{C}(\theta) - L^\text{S}(\theta)\]Now let’s put all of the pieces together into the online A2C algorithm.

- For each episode do

- For each step do

- Sample the action $a\sim\pi_\theta(s)$ and store $\log\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$

- Execute the action $a$ to receive a reward $r$ and store it.

- If the episode is not done, skip to the next iteration.

- Compute the list of discounted rewards using the discount factor: $R_t = \sum_{t’=0}^t \gamma^{t’} r_{T-t’}\gets [r_T, r_T+\gamma r_{T-1}, r_T+\gamma r_{T-1}+\gamma^2 r_{T-2}, \dots]$.

- Normalize the rewards by subtracting the mean $\mu_R$ and dividing by the standard deviation $\sigma_R$ (and adding in an epsilon factor $\epsilon$ to prevent dividing by zero): $R_t\gets\frac{R_t-\mu_R}{\sigma_R+\epsilon}$.

- Compute the advantages using the target values $R_t$ and critic head $V(s_t)$: $A(s, a) = R_t - V(s_t)$.

- Compute the actor/policy loss by multiplying the negative log probabilities with their respective advantages and average: $L^\text{A}(\theta) = \frac{1}{N}\sum_i\sum_t -\log\pi_\theta(a_t^{(i)}\vert s_t^{(i)})\cdot A(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)})$.

- Compute the critic/value loss by taking the average of the Huber loss of the advantages: $L^\text{C}(\theta) = \frac{1}{N}\sum_i \sum_t \mathcal{L}_1(A(s_t^{(i)}, a_t^{(i)}))$

- Compute the entropy penalty and average: $L^\text{S}(\theta) = \sum_a \pi_\theta(a\vert s)\cdot\log\pi_\theta(a\vert s)$

- Combine the losses: $L(\theta) = L^\text{A}(\theta) - L^\text{C}(\theta) - L^\text{S}(\theta)$

- Backpropagate $L(\theta)$ through the policy network.

- Update the policy network’s parameters.

- End for

- For each step do

- End for

We can take this architecture and asynchronize and parallelize it into an Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic (A3C) network by running independent agents on separate worker threads and asynchronously updating the parameters of the actor and critic networks. This can run into issues because some agents might be using outdated parameters of both networks.

A synchronous, i.e., A2C, architecture can also be parallelized, but we would wait for each agent to finish playing before averaging each agent’s gradient and updating the networks’ parameters. This ensures that, on the next round, each agent has the latest parameters.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is a style of policy algorithm that has shown incredible results in very complicated games such as DOTA 2, even beating out expert gamers.

To understand PPO, let’s go back to policy gradients. Recall the loss of the policy gradient.

\[L^{\text{PG}}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_t [\log\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t) A_t]\]where $A_t$ is the estimator for the advantage function. (The subscript $t$ is functionally the same as the $\tau\sim\pi_\theta(\tau)$ subscript for policy gradients we used earlier.)

Policy gradients increase the likelihood of actions that produced higher rewards and decrease those that produced lower rewards. This loss function had its own set of issues, namely slow rates of convergence and high variability in training causing the policy to potentially change drastically between two updates.

The last problem is a very undesirable property of policy gradients so Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) aimed to mitigate this by using a surrogate loss function and adding an additional constraint to the optimization problem.

Instead of using the log likelihood, the surrogate function uses the ratio of the action probabilities using current and old parameters.

\[r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_\text{old}}(a_t\vert s_t)}\](This ratio function is different from the reward function $r(\tau)$ we considered at when deriving policy gradients.)

If $r_t(\theta) > 1$, then $a_t$ is more likely for the current parameters $\theta$ than it was for the old parameters $\theta_\text{old}$. On the other hand, $0 < r_t(\theta) <= 1$ if $a_t$ is less or equally likely using the current parameters as opposed to the old parameters. We call this ratio function a surrogate function because it stands in for the log likelihood function in vanilla policy gradients.

Now we can replace the log likelihood with this new metric in the loss function.

\[L^{\text{TRPO}}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_t \bigg[\frac{\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_\text{old}}(a_t\vert s_t)} A_t\bigg] = \mathbb{E}_t \big[ r_t(\theta) A_t\big]\]However, we need to add an additional constraint to prevent the policy from drastically changing, as it could do with vanilla policy gradients. The original TRPO paper suggests using Kullback-Leibler divergence (KL divergence) as a hard constraint:

\[\text{maximize}_\theta~~~~\mathbb{E}_t \bigg[\frac{\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_\text{old}}(a_t\vert s_t)} A_t\bigg]\\\\ \text{subject to}~~~~\mathbb{E}_t \big[ \text{KL}(\pi_{\theta_\text{old}}(\cdot\vert s_t), \pi_\theta(\cdot\vert s_t))\big] \leq \delta\]where $\delta$ is some maximum threshold.

If you’re unfamiliar, the KL divergence is a metric that measures the difference between two probability distributions $P$ and $Q$.

\[\text{KL}(P,Q) = \sum_i P_i\log\frac{P_i}{Q_i}\]Intuitively, this new constraint says that the difference in the action distributions of the new and old policies can’t exceed a maximum value $\delta$.

Instead of a hard constraint, we can actually include it in the objective function as a penalty with a hyperparameter $\beta$ controlling the strength.

\[\mathbb{E}_t \bigg[\frac{\pi_\theta(a_t\vert s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_\text{old}}(a_t\vert s_t)} A_t - \beta~\text{KL}(\pi_{\theta_\text{old}}(\cdot\vert s_t),\pi_\theta(\cdot\vert s_t))\bigg]\]Incorporating KL divergence either way helps discourage large changes in the policy for each update.

The trust region (blue) is centered around a point in the state-action space. We strongly discourage our policy update from moving outside of this region to prevent large changes in the policy.

However, computing the KL divergence is expensive, especially for large action distributions! Instead, we can embed the notion of smaller policy updates into the objective function itself, which is exactly what PPO does. PPO introduces this strange, but effective and efficient, objective function.

\[\mathcal{L}^{\text{CLIP}}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_t \bigg[ \min(\underbrace{r_t(\theta)A_t}_\text{TRPO}, \underbrace{\text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1-\varepsilon, 1+\varepsilon)A_t)}_\text{clipped surrogate})\bigg]\]where $\varepsilon$ is a hyperparameter that controls the range of the ratio function. ($\varepsilon=0.2$ in the PPO paper)

In this new objective function, the minimum is taken between the original TRPO objective and this new clipped term. By clipping the surrogate function to $[1-\varepsilon, 1+\varepsilon]$, we discourage it from significantly deviating from 1. In other words, we discourage updates where there are large difference between the new and old policies. This clipping is functionally similar to TRPO’s KL divergence except it’s much easier to compute!

Finally, we take the minimum of the clipped and unclipped objectives, which gives us the lower bound of the objective. It’ll become apparent why take the minimum in just a moment.

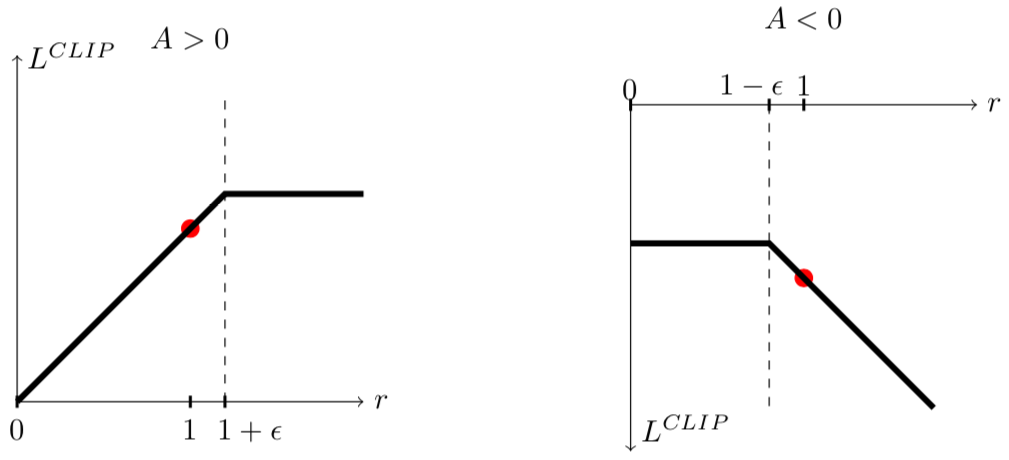

With this new objective function, there are two cases to consider here: $A > 0$ and $A < 0$.

Clipped objective function.

Recall that if $A > 0$, then our action was good. In this case, $r(\theta)$ will be clipped if it is too high, i.e., one action is far more probable with this set of parameters compared to the old ones, even though this action is good. This is because we want to avoid taking large jumps in policy and overshooting, so clipping the objective ensures that we don’t take a step that’s too large. On the other hand, $A < 0$ means our action was bad. In this case, we clip $r(\theta)$ so that it doesn’t make the bad action drastically less probable. In both cases, we don’t want to update our policy drastically.

One last bit about this objective function is that $r(\theta)$ is unbounded to the right when $A < 0$. This is the scenario where the action taken was a bad action and it became more probable compared to the last parameter update! This is not good! Fortunately, by leaving it unbounded, the gradient step will move in the opposite direction because the value of the objective function is negative. Furthermore, it will take a step proportional to how bad this new action is. Intuitively, this allows us to correct our actions when we make a big mistake.

Here is where we get to the min function in the objective function. The min function enables us to take that corrective step backwards. When it is invoked, the unclipped value of $r(\theta)A$ will be returned, thus allowing our agent to take that corrective step.

If you read the paper, it’ll go on to introduce a Adaptive KL Penalty Coefficient that adjusts the value of $\beta$ in the full KL-penalized TRPO objective, as well as reference the same entropy penalty with A2C. However, the essence of PPO is really embodied in $L^{\text{CLIP}}(\theta)$.

Since each PPO step makes smaller changes to the policy, we can actually train several epochs on the same minibatch of data! This consideration is factored in to the new PPO algorithm:

- For each iteration do

- For each actor $1,\dots,N$ do

- Run $\pi_{\theta_\text{old}}$ for $T$ time steps

- Average the advantage estimate

- Optimize surrogate $L(\theta)$ with $K$ epochs and a minibatch size of $M \leq NT$.

- $\theta_\text{old}\gets\theta$

- For each actor $1,\dots,N$ do

This is in the style of A3C so we have asynchronous actors, but we could use a synchronous implementation. Notice that we optimize the surrogate function for several epochs on the same minibatch of data. The hyperparameters suggested in the paper are $K=[3,15]$, $M=[64,4096]$, and $T=[128,2048]$.

Proximal Policy Optimization is the culmination of policy-based methods, at the time of this post at least. OpenAI Five has won games against human players in DOTA 2 where the horizon of moves is 20,000, the action space is ~170,000, and the observation space uses 20,000 unique floating-point numbers. All of this was accompanied by 256 P100 GPUs and 128,000 CPUs.

Conclusion

Policy-based or hybrid value-policy techniques seem to be consistently outperforming value-based methods on complicated tasks. Policy gradients look at stochastic policies and directly update them rather than computing them from values. Advantage Actor-critic (A2C) and Asynchronous Advantage Actor-critic (A3C) take hybrid approaches by intertwining a value-based network and policy-based network. Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is a class of algorithms that helps mitigate large changes in the policy to stabilize learning and ultimately produce more sophisticated reinforcement learning agents.

I hope this post has shed some light on a few of the policy-based algorithms use 🙂