Depth Perception: The Next Big Thing in Computer Vision

Depth perception is the ability of a device to gather 3D depth information about their environment, relative to the position of the device. We can do many things with just depth information:

- Teach a robot to avoid walls

- Detect hand pose

- Build a Stanford bunny

Although we can accomplish much using just depth information, we can accomplish even more when we merge it with image data taken from a camera. Specifically in the realm of computer vision, we can use depth information to augment our cameras by giving us an entirely new spatial dimension to use.

A Little History

Combining camera and depth information is not new. There have been consumer devices, like the Microsoft Kinect, that use images and depth to detect body pose. The Kinect is a stationary device however. Dragging a Kinect with you wherever you go doesn’t seem like a good idea. Wouldn’t it be great if we could use depth information to improve our daily lives on-the-go?

The revolutionary Peanut phone. It’s very chunky for a phone from 2014, but that’s because it’s stuffed with high-fidelity sensors. Only 200 of these went out to research labs, universities, and developers around the globe.

Enter Google Tango. Back in 2014, led by Johnny Lee, Google’s research division ATAP was able to condense the necessary sensors into a smartphone called the Peanut phone in-testing. The Peanut phone housed an infrared depth sensor that it used to gather depth information along with a myriad of other sensors already found on most modern smartphones. They also gave it a 170-degree fisheye camera for tracking the device along all three spatial dimensions. The Peanut phones were discontinued and replaced with the Yellowstone 7-inch tablets with similar specifications and even more computing power.

The first consumer device with depth-sensing capabilities: Lenovo Phab 2 Pro. Much less chunkier than the Peanut phone. And it only took two years to go from research prototype to fully-fledged consumer device!

Now let’s skip ahead to 2016. The first Tango-enabled phone, the Lenovo Phab 2 Pro, appeared on the market just last year in 2016. Similar to its ancestors, it housed a depth camera and a 16MP wide-angle camera. At the past Google I/O, there were many talks that showcased not only the capabilities of Tango, but also the APIs that can allow developers to take full advantage of the Tango’s multitude of sensors for their own app. Tango devices aren’t just some fancy, flashy devices used only for demos; they have an ever-growing set of APIs that developers can easily use to add more functionality their app.

Microsoft’s augmented reality headset: the HoloLens. When I put it on, it was a bit heavier than I expected, but that’s because it’s also full of awesome sensors and the entirely of Windows as well.

Microsoft has started to buy into this notion of depth sensing because they developed the HoloLens, which first shipped in 2016. The HoloLens takes all of the awesome aspects of Tango and puts it in a wearable visor. Since you don’t need to hold up HoloLens, they’ve also added some gesture support, though they discourage people from creating their own gestures. Unfortunately, the HoloLens is much more expensive than Tango ever was (about $3000), but it’s also a complete Windows PC. I suspect the price point for this will go down in the coming years as it did with Tango (originally $1024).

Both of these devices produce amazing AR and VR experiences. If we look at their hardware, we see points of commonality.

- gyroscopes, accelerometers, magnetometers, etc. HoloLens merges most of this together into a single Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU)

- regular (visible spectrum) cameras

- depth cameras

There are also some interesting points of difference.

| HoloLens | Tango (tablets) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2GB of RAM | 4GB of RAM | RAM doesn't seem to be emphasized on these devices |

| Holographic Processing Unit (HPU) | NVidia Tegra TK1 | The HPU seems to be a trade secret, but if it's similar to Tango, expect it to be very powerful, specifically at matrix math |

| 4 cameras and microphones | 1 Fisheye-lens camera | Both use sensor fusion to combine (visible spectrum) camera data, but the HoloLens has much more of it |

It’s this hardware that allows devices like Tango and HoloLens to create those augmented reality experiences, and it’s worked out spectacularly in both cases. I suspect the hardware on these devices will becomes templates for devices manufacturers building depth-capable devices.

Augmented Reality

As I’ve mentioned before, one thing that depth information is particularly useful for is augmented reality. Since Tango’s release, there have been many augmented reality apps for Tango that take full advantage of the slew of sensors to produce an immersive augmented reality experience. This level of immersion can only be accomplished when we have access to depth information, along with other sensors.

Think about it like this:

Reality is in 3D; to augment it, in the first place, we need to capture its full depth and richness.

This statement is the culmination of months of thought I spent trying to answer the question “why does depth information even matter when it comes to augmented reality.” To begin to augment reality, we have to consider that reality is in 3D, and depth information is what we use to measure 3D spaces. To perform any visualizations or drawings in a space, depth information is useful to have, and the software can use this information in a few key ways to provide that immersive experience.

Area Learning

Tango’s area learning uses mysterious features to capture information about a space and store it in an Area Description File (ADF). These files have quick-indexing characteristics so Tango can immediately recognize if it has been in this space before.

We can take depth information a step further and “remember” a space. Tango calls this area learning and only gives a high-level definition of how it works on their website:

“Area Learning gives the device the ability to see and remember the key visual features of a physical space—the edges, corners, other unique features—so it can recognize that area again later.”

Tango probably uses a slew of sensors and camera data (SIFT/SURF/ORB features, randomly-sampled depth data, location, etc) and sensor fusion algorithms to find features to “remember” spaces. Regardless of how, the notion of “remembering a space” vastly improves the AR experience. It’s what allows devices like HoloLens to “remember” that you put a browser window on your office wall when you leave and come back. In my own tinkering with the Yellowstone tablets, area learning also drastically reduces drift errors from motion tracking.

Motion Tracking

![]()

Motion tracking is actually tracking the path of the Tango device, relative to when we started an application. Using gyroscope, accelerometer, and depth data, we can position our device in a 3D space.

Since I brought it up, I might as well mention something about motion tracking. First of all, it has a confusing name because motion tracking in the traditional computer vision sense means that we’re interested in tracking a particular object through frames of a video. In the context of Tango, we’re tracking the device itself through 3D space. While this isn’t something that necessarily requires depth information (you might be able to manage using optical flow), it certainly helps improve accuracy and reduces drift errors. Motion tracking, in Tango context, combines with area learning to help position the user as well as any visualizations in the learned space.

Surface Reconstruction

To put the icing on the cake, the HoloLens has built-in surface reconstruction it calls spatial mapping. Speaking from experience, real-time mesh generation is incredibly complicated, and it’s laborious to get an accurate mesh in real-time. Even if you write the algorithm correctly, there’s still no absolute guarantee that it won’t close gaps that are actually open doors or windows. (Though heuristics can help minimize this!) Real-time surface reconstruction is the most important use of that depth sensor. We don’t want visualizations going through walls! They should be on the surface, not in the surface. The whole point of surface reconstruction is to figure out what those surfaces are! (Surface reconstruction is certainly available on Tango as well, but it’s not built-in from what I recall.)

Conclusions

All of the algorithms/techniques/concepts that I’ve discussed provide the user with an immersive AR experience. All of these algorithms/techniques/concepts require a device with depth-sensing capabilities among other hardware. Currently, depth-sensing devices are few and far between, but, since I last worked on surface reconstruction in 2014, we’ve had our first consumer depth-sensing device in 2016: the Lenovo Phab 2 Pro. That’s a pretty good start considering the Peanut phone was brand new just two years before the Phab 2 Pro! Devices like these and the HoloLens are going to pioneer a new wave of consumer device equipped with depth-sensing capabilities and sensor fusion, just like the first camera-phones revolutionized the mobile industry. And look at where we are now with smartphone cameras. The iPhone 7 Plus even has two cameras!

Depth perception on mobile devices is something to keep an eye on as we move forward with augmented reality.

(By the way, watch this talk by Tango Lead Johnny Lee at Google IO to see a ton of cool Tango demos!)

Sidebar: How does depth perception actually work?

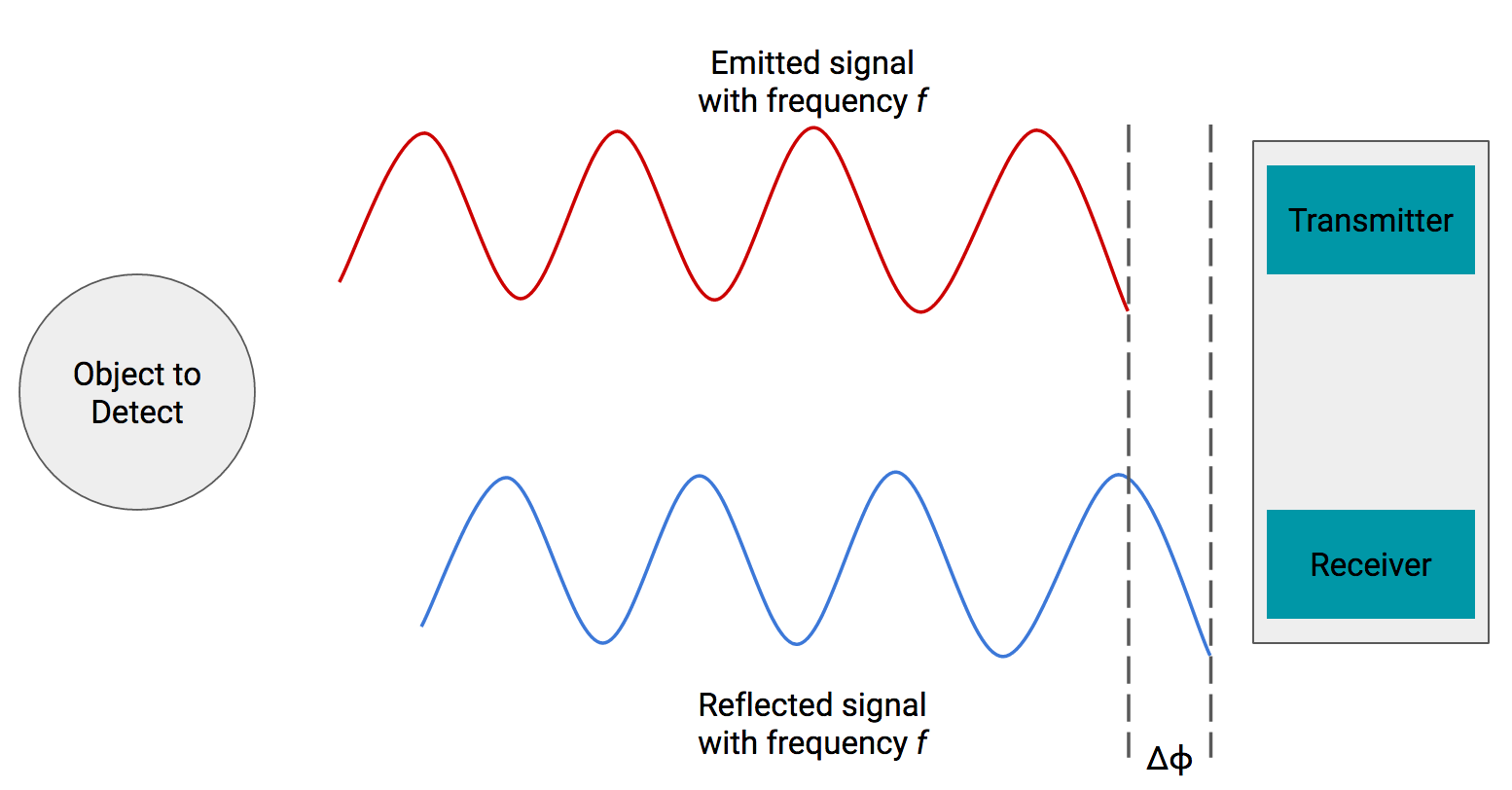

In most devices like Tango and the HoloLens, depth is usually determined using infrared sensors and a technique called time-of-flight.

We need an IR transmitter and receiver. The transmitter will send an infrared signal at a particular frequency, and the receiver will collect that same signal. Since we’re using infrared, an electromagnetic wave, we know it must travel at the speed of light. When the signal hits the receiver, since it must have traveled a nonzero distance, there’s going to be some time shift in our signal.

Knowing the just the frequency and time shift, we can compute how far away the object was when the signal bounced off of it.

In essence, an IR transmitter and receiver is all we need, but the sensors on devices used in research are usually advanced enough to capture thousands of data points per second.