Language Modeling - Part 2: Embeddings

In the previous post, we discussed n-gram models and how to use them for language modeling and text generation. If use large-enough n-grams (say $n=6$), we could get pretty decent generated text. However, the caveat with n-gram model is in the representation: these models represent words as strings. This is not ideal since they don’t capture anything about the actual meaning of the word. For example, suppose we were generating text with the sequence “The delicious world-class coffee was”. The n-gram model might output both $p(\text{great}\vert\text{The delicious world-class coffee was})$ and $p(\text{terrible}\vert\text{The delicious world-class coffee was})$ with high probabilities depending on the training set and value of $n$! The words “great” and “terrible” have opposite meaning however. The n-gram model can’t quite understand that these are opposite words because it simply represents words as strings which don’t actually capture meaning or relations.

Can we come up with a better word representation that actually models word meanings and relations? In this post, I’ll go over how to compare words and how to quantify that similarity of words. As always, we’ll start with some background in linguistics. Then, before getting into word similarity, we’ll actually talk about document similarity, since it’s a bit easier to understand, and use those concepts to finally talk about embeddings which are vector representations of words that capture meaning. Finally, we’ll see some tangible examples with code on how to load pretrained embeddings, perform analogy tasks, and visualize them.

Semantics of Words

Similar to the previous discussion on n-grams, since we’re talking about representing meanings of words, we have to understand what that entails linguistically first. n-gram models represent words as strings which doesn’t capture the meaning or connotation of the word in question. For example, some words are synonyms or antonyms of other words; some words have a positive or negative connotation; some words are related, but not synonymous to other words. A good representation should capture all of that.

Let’s start with synonyms as an example: one way to say two words are synonyms is if we can substitute them in a sentence and still have the “truth conditions” of the sentence hold. However, just because words are synonyms doesn’t mean they’re interchangeable in all contexts. For example, $H_2 O$ is used in scientific contexts but strange in other contexts. Furthermore, words can be similar without being synonyms: tea and biscuits are not synonyms but are related because we often serve biscuits with tea.

One methodology linguists came up with to quantify word meaning in the 50s (Osgood et al. The Measurement of Meaning. 1957) is quantifying them along three dimensions: valence (pleasantness of stimulus, e.g., happy/unhappy), arousal (intensity of emotion of the stimulus, e.g., excited/calm), and dominance (degree of control of the stimulus, e.g., controlling/influenced). Linguists asked groups of humans to quantify different words based on those dimensions. From the results, they could numerically measure similarity and relationships of words using those three dimensions. With this representation, we could map a word to a vector in a 3D space and perform arithmetic operations to compare two words along those hand-crafted features. This was a good start but depended on surveying humans to come up with these values when large corpora of human text already exists.

Comparing Documents

Gathering large groups of people to quantify words along those dimensions isn’t a practical way of doing things, but it provides some insight: we can try to come up with an automated mechanism to map a word to a vector that we can perform mathematical operations on. The key insight lies in what linguists call the distributional hypothesis: words that occur in similar contexts have similar meanings. So the idea is to construct this vector representation for a particular word based on the context that word appears in.

Counter-intuitively, figuring this out for documents of words is a bit easier than individual words themselves so let’s sojourn into the world of information retrieval (IR). Given a query $q$ and a set of documents $\mathcal{D}$ (also called a corpus), the problem of information retrieval is to find a document $d\in\mathcal{D}$ such that it “best matches” the query $q$. Based on the distributional hypothesis, one way to compare two documents would be to look at how many words co-occur across documents. For each word in each document of the corpus, we can create a word-document matrix where the rows are words, the columns are documents, and an entry in the matrix represents the number of times a particular word appeared in a particular document.

| As you like it | Julius Caesar | Henry V | |

|---|---|---|---|

| battle | 1 | 7 | 13 |

| good | 114 | 62 | 89 |

| fool | 20 | 1 | 4 |

Source: Speech and Language Processing by Dan Jurafsky and James H. Martin

In this example, we can see that Julius Caesar has more in common with Henry V than it does with As you like it because the counts are more similar to each other. Quantitatively, we can represent each document as a vector of size $\vert V\vert$ where $\vert V\vert$ represents the size of the vocabulary (all words across all documents). So we can represent Julius Caesar and Henry V as two $\vert V\vert$-dimensional vectors, but how do we compare them?

One straightforward comparison is using the Euclidean distance between vectors:

\[d(v, w) = \sqrt{v_1 w_1+\cdots+v_{N}w_{N}}\]However, that would disproportionally give a higher weight to vectors of greater magnitude. We can normalize against both of the vector sizes and drop the square root (since similarity is relative anyways) and we get a simpler notion of distance.

\[d(v, w) = \frac{v_1 w_1+\cdots+v_{N}w_{N}}{|v||w|} = \frac{v\cdot w}{|v||w|}\]This measure of similarity is called cosine similarity or also the normalized dot product because of the equation $a\cdot b = \vert a\vert\vert b\vert\cos\theta$. This distance metric is bounded to be in $[-1, 1]$ where a similarity of 1 means the vectors are maximally similar (pointed in the same direction), a similarity of 0 means the vectors are unrelated (orthogonal), and a similarity of -1 means the vectors are maximally dissimilar (pointing in opposite directions). Using this measure, we can compare two documents against each other and quantify their similarity!

tf-idf

One large issue with directly using the term-document matrix is article words. Words like “the”, “a”, “an” are words that occur frequently across all documents. They don’t have any discriminative power when it comes to comparing two documents since they occur too frequently. So we need to balance words that are frequent against words that are too frequent. To quantify this, we define term frequency as the frequency of a word $t$ in a document $d$ using the raw count.

\[\text{tf}_{t,d} = \text{count}(t, d)\]Word frequencies can become very large numbers so we want to squash the raw counts since they don’t linearly equate to relevance. But what if a word doesn’t occur in a document at all? Its count would be 0, which ends up becoming a problem when we take a log. We can simply offset the raw count by 1 to avoid numerical issues and use the log-space instead of the raw counts.

\[\text{tf}_{t,d} = \log\Big(\text{count}(t, d) + 1\Big)\]Similarly, we can define document frequency as the number of documents that a word occurs in: $\text{df}_t$. Inverse document frequency (idf) is simply the inverse using $N$ as the number of documents in the corpus: $\text{idf}_t=\frac{N}{\text{df}_t}$. Similar to the above rationale, we also use the log-space.

\[\text{idf}_t = \log\frac{N}{\text{df}_t}\]The intuition is that frequent words are more important than infrequent ones, but, the fewer documents that a word occurs in should have a higher weight since it has more discriminative power, i.e., it uniquely defines the document. Combining these two constraints, we get the full tf-idf weight

\[w_{t,d} = \text{tf}_{t,d}\text{idf}_t\]Note that this ensures that really common words would have $w\approx 0$ since their idf score would be close to 0. With the earlier table, let’s replace the raw counts with the tf-idf score for each entry in the word-document matrix.

| As you like it | Julius Caesar | Henry V | |

|---|---|---|---|

| battle | 0.074 | 0.22 | 0.28 |

| good | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| fool | 0.019 | 0.0036 | 0.022 |

Source: Speech and Language Processing by Dan Jurafsky and James H. Martin

Notice that since “good” is a very common word, it’s tf-idf score becomes 0 since it has no discriminative power. Using tf-idf provides a better way to compare documents by more accurately representing their word contents.

Embeddings

We’ve seen how to represent documents as large, sparse vectors of word counts/frequencies and how to compare against each other using various techniques. Let’s see how to compare individual words using embeddings. An embedding is a short, dense vector representation of a word that holds particular semantics about that word. In practice these dense vectors tend to work better than sparse vectors in most language tasks since they are more efficient with capturing the complexity of the semantic space than sparse vectors.

word2vec

One way to construct an embedding for a vector is to go back to that distribution hypothesis: words that occur in similar contexts have similar meanings. This is the principle behind word2vec: we want to train a model that tells us if a word is likely to be near another word. Through training a word2vec model, the weights of the model become the embedding and we’ll learn them for each word in the vocabulary in a self-supervised fashion with no explicit training labels.

There are two flavors of word2vec: continuous bag of words (CBOW) and skip-gram; we’ll use the skip-gram model. The intuition is that we select a target word and define a context window of a few words before and after the target word. We construct a tuple of the target word and each of the words in the context window, and these become our training examples. We learn a set of weights to maximize the likelihood that a context word appears in the context window of a target word and use the learned weights as the embedding itself.

Let’s start with constructing the training tuples. Suppose we have the following sentence and the target word was “cup” and the context window was $\pm 2$:

\[\text{[The coffee }\color{red}{\text{cup}}\text{ was half] empty.}\]The training examples would be tuples of the target word and the context words: (cup, the), (cup, coffee), (cup, was), (cup, half). We want to train a model such that, given a target word and another word, it returns the likelihood that the other word is a context word of the target word.

For the input, we represent words as sparse one-hot embeddings where the size of the vector is the size of the vocabulary and we assign a unique dimension/index in the vector to each word.

\[\text{cup}\mapsto\begin{bmatrix}0\\\vdots\\ 0\\ 1\\ 0\\\vdots\\ 0\end{bmatrix} = w\\\]Then we have a weight matrix $E$ that maps this one-hot vector to its embedding vector of some dimensionality $H$, so the dimensions of the matrix must be $H\times\vert V\vert$. We can get the embedding for a word in its one-hot representation by multiplying $Ew$ to get an output embedding vector of size $H\times 1$ that corresponds to the same row in the matrix. Note that this is equivalent to “selecting” the row of the one-hot embedding. For this reason, we also call $E$ the embedding matrix itself.

Recall that to train the model, we want it to produce a high likelihood if a context word is indeed in the context of the target word. To do that, we need another matrix mapping the embedding space back into the vocab space $E’$ of dimension $\vert V\vert\times H$. Since we want a probability, we need to normalize the output so we get a probability distribution across the vocabulary words. To do this, we apply the softmax operator:

\[\text{softmax}(z_i) = \frac{\exp(z_i)}{\sum_j \exp(z_j)}\]Intuitively, this takes a particular element $z_i$ and divides it by the total sum of all elements in the exponential space. This gives us a valid probability distribution as the output. For the context word, we use the one-hot embedding. Another way to interpret the one-hot embedding probabilistically is that it represents a distribution with a single peak at a single index/word.

Now that we have the normalized output distribution and a one-hot embedding (thought of as a peaked distribution), the intuition behind the loss function is that we want to push the output distribution to be peaked in the same index as the desired embedding. One loss function that has this property is called the cross-entropy (CE) loss between a target $y$ and predicted $\hat{y}$.

\[\mathcal{L}(\hat{y}, y) = -\sum_i y_i\log\hat{y}_i\]Note that because the target vector $y$ is a one-hot embedding, almost every term in the sum will $0$ except the one where $i=c$ where $c$ is the index of the context word in the target vector is and the element value is simply $1$. So we can simply this into a single expression.

\[\mathcal{L}(\hat{y}, y) = -\log\hat{y}_c\]Does this loss function do the right thing? What happens if $\hat{y}_c$ is very close to $0$? Intuitively, this means the model is not doing a good job since it estimates the context word with a low probability of being in the actual context. In this case, we’re taking the log of a very small number which is a very large negative number. After we negate it, we get a very large loss. This makes sense since our model is saying that it doesn’t think the context word has a high likelihood of being in the context window even though it actually is (because that’s how we constructed the dataset). Note that since $\hat{y}_c$ is the output of a softmax, it’s bounded to be in $[0, 1]$. Since we can’t take the log of $0$, we often add a little epsilon $\varepsilon$ inside the log like $\log(\hat{y}_c+\varepsilon )$ for numerical stability.

Now what happens if $\hat{y}_c$ is close to $1$? Intuitively, this means our model is doing great because it’s very confidently estimating that the context word is in the context window. In this case, the log of $1$ is $0$ so we have a loss of $0$. This makes sense since our model is accurately predicting the high likelihood of the context word being in the context window.

Overall, this loss function seems to do what we want: move the predicted distribution of the model to be peaked at the context word. Putting all of this together, the training process looks like the following.

- Given a target word $w$ and context word, run the target word through the matrices $E’Ew$.

- Take the softmax of the output layer $\text{softmax}(E’Ew)$ to get a distribution over the vocab.

- Compute the cross-entropy loss using the one-hot embedding of the context word.

- Update the weights of the matrix according to the loss.

Practically, we’d use a framework such as Pytorch or Tensorflow and their automatic differentiation (also called autograd for automatic gradient) to compute the gradients for us. After training, we have an embedding matrix $E$ such that each row is an embedding vector that we can look up for a particular word in our vocabulary.

GloVe

word2vec is a good start in providing us with a word representation that holds some semantics about the word but it has one major problem: the context is always local. When we create training examples, we always use a context window around the word. While this gives us good local co-occurrences, we could more accurately represent the word if we also looked at global co-occurrences of words. Rather than trying to learn the raw probabilities like what word2vec does, GloVe aims to learn a ratio of probabilities representing how much more likely is it that a particular word appears in a context of one word compared to another word.

To start with some notation, we define a word-word co-occurrence matrix with $X$ and let $X_{ij}$ represent the number of times word $j$ appeared in the context of word $i$. With that definition, let $X_i = \sum_j X_{ij}$ as the number of times any word appears in the context of word $i$; we can also define $p_{ij}=p(j\vert i)=\frac{X_{ij}}{X_i}$ as the probability that word $j$ appears in the context of word $i$. As an example, consider $i=\text{ice}$ and $j=\text{steam}$. With probe words $k$, we can consider the ratio $\frac{p_{ik}}{p_{jk}}$ that tells us how much more likely is word $k$ to appear in the context of word $i$ than word $j$. For words like $k=\text{solid}$ that are more closely related to $i=\text{ice}$, the ratio will be large; for words more closely related to $j=\text{steam}$ like $k=\text{gas}$, the ratio will be small. For words that are closely related to both such as $k=\text{water}$, the ratio will be close to 1. This ratio has more discriminative power in identifying which words are relevant or irrelevant than using the raw probabilities.

Rather than learning raw probabilities, the authors construct a model to learn the co-occurrence ratios and train it using a novel weighted least squares regression model.

\[J = \sum_{i,j} f(X_{ij})\Big(w_i^T \tilde{w}_j + b_i + \tilde{b}_j - \log X_{ij} \Big)^2\]where

- $w_i$ is a learned word vector

- $\tilde{w}_j$ is a learned context vector

- $b_i$ is the learned bias of word $i$

- $\tilde{b}_j$ is the learned bias of context word $j$

- $f(x) = \Big(\frac{x}{x_\text{max}}\Big)^\alpha$ if $x < x_\text{max}$ or $1$ otherwise is a weighting function.

There are a few nice properties about this weighting function that carry over from tf-idf: $f(x)$ is non-decreasing so that more frequent words are weighted correctly but it has an upper bound of $1$ so that very frequent words are not overweighted. The additional numerical property required by this function is that $f(0) = 0$ else a co-occurrence entry could be 0 and the entire function would be ill-defined. The hyperparameters are $x_\text{max}$ and $\alpha$ and the authors found that the former doesn’t impact the quality as much as the latter; $\alpha=0.75$ tended to work better than a linear model, empirically. Solving for the weights, we get GloVe embeddings that can be used just like word2vec embeddings but they tend to perform better since we’re also considering global word co-occurrences in additional to local context windows. We’ll see an example later where we load pretrained GloVe embeddings and use them to solve word analogies.

Read the GloVe paper for more details!

Embedding Layer

Both word2vec and GloVe train embeddings that can be used across a number of different language modeling tasks. However, the cost to pay for the generalization is that they may not perform as well for very specific applications. In other words, since the embeddings are taken off-the-shelf, we’ll have to fine-tune them for a specific language modeling task. We can use the pretrained embeddings to start and then consider them to be “optimizable” variables as a smaller part of our language model. This gives us a good start but also allows us to fine-tune the pretrained embeddings for our particular language modeling task.

In some cases, it may be beneficial to actually train an embedding layer from scratch end-to-end as part of whatever the language modeling task-of-interest is. The training procedure is similar to word2vec in that we start with one-hot embeddings of the words and them map them into an embedding space with an embedding matrix, but then the output directly goes into the next layer or stage in the language model. When we train the language model, the gradients automatically update the embedding matrix based on the overall loss of the language modeling task. While this method does tend to produce more accurate results for the end-to-end task, it does require a large corpus to train since we’re training the embeddings from scratch along with the rest of the language model rather than pulling the embeddings off-the-shelf.

Semantic Properties

After we’ve trained embeddings, we can see how well they model word semantics. One canonical task that demonstrates semantic analysis is completing a word analogy. For example, “man is to king as woman is to X”. The correct answer is “queen”. If our embeddings are truly learning correct semantic relationships, then they should be able to solve these kinds of analogies. We can represent these in the embedding space with vector arithmetic (since vector spaces are linear) and look at which other embeddings lie close to the result.

\[\overrightarrow{\text{king}} - \overrightarrow{\text{man}} + \overrightarrow{\text{woman}} \approx \overrightarrow{\text{queen}}\]In other words, the embedding for “king” minus the embedding for “man” plus the embedding for “woman” should be close to the embedding for “queen”. This turns out to be true for word2vec and GloVe embeddings! So it seems like they are actually capturing certain kinds of semantic relations. Let’s actually write some code to load some pre-trained GloVe embeddings and show this!

First, we’ll need to go to the official GloVe website and download the pre-trained embedding and unzip them. For this example, we’ll use the glove.6B.zip with 100-dimensional GloVe embeddings. Each line in the text file is the word followed by the values of the embeddings so we can load that into a dictionary for easy lookup. Let’s try computing the similarity of $\overrightarrow{\text{king}} - \overrightarrow{\text{man}} + \overrightarrow{\text{woman}}$ and $\overrightarrow{\text{queen}}$ and also an unrelated word like $\overrightarrow{\text{egg}}$ and see if the embeddings correctly note similarities.

import numpy as np

from numpy import dot

from numpy.linalg import norm

embedding_dim = 100

# Define the local path to save the downloaded embeddings

glove_filename = f"glove.6B/glove.6B.{embedding_dim}d.txt"

# Load the GloVe embeddings into a dictionary

e = {}

with open(glove_filename, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as f:

for line in f:

values = line.split()

word = values[0]

embedding = np.array(values[1:], dtype='float32')

e[word] = embedding

# compute analogy

result = e['king'] - e['man'] + e['woman']

# cosine similarity of the result and the embedding for queen

cos_sim = dot(result, e['queen']) / (norm(result) * norm(e['queen']))

print(cos_sim)

# cosine similarity of the result and the embedding for egg

cos_sim = dot(result, e['egg']) / (norm(result) * norm(e['egg']))

print(cos_sim)

The cosine similarity for the result and queen is $0.7834413$ while the cosine similarity for the result and egg is only $0.19395089$. As expected, “queen” is a far more appropriate solution to the word analogy than “egg”!

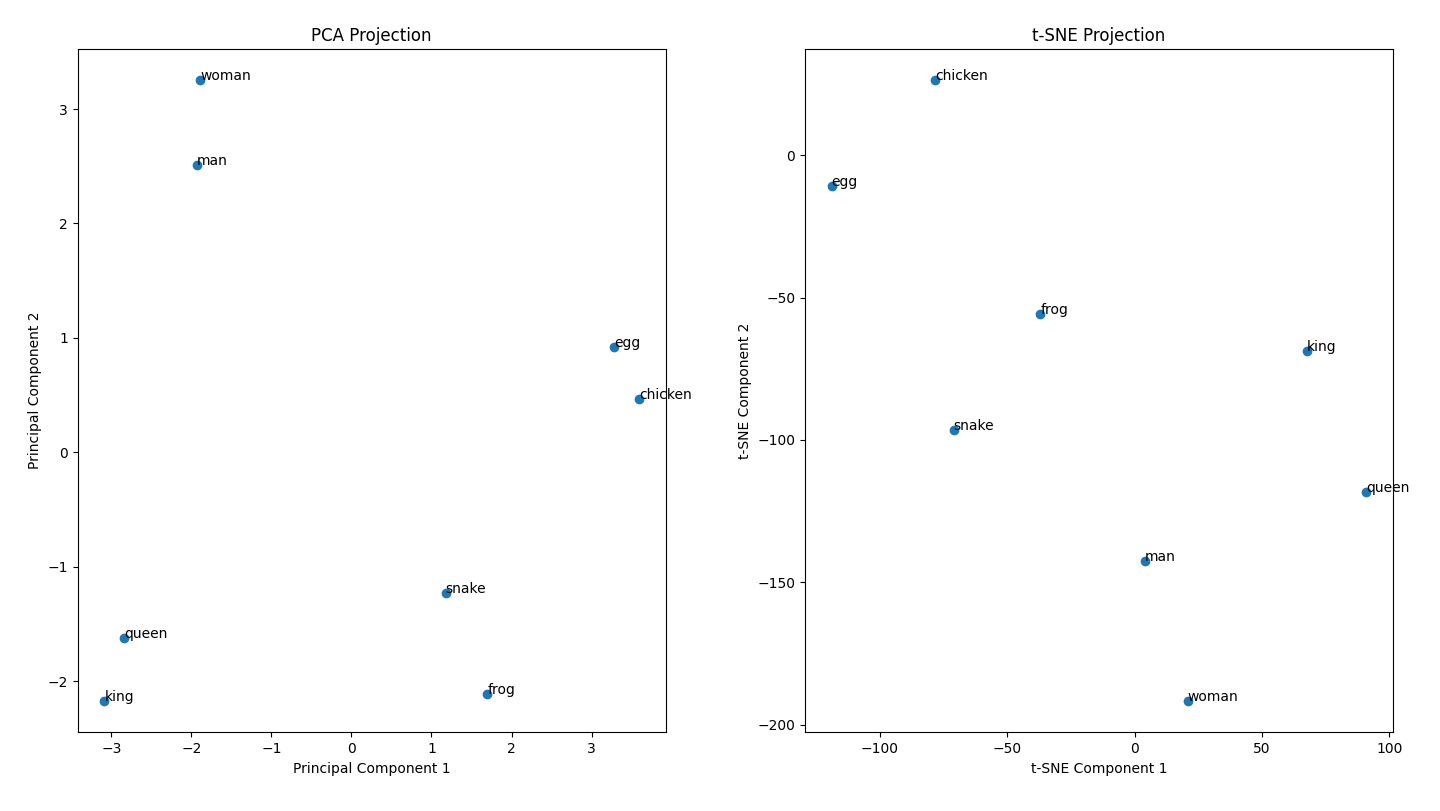

It would be nice to visualize the embeddings of different words relative to each other. However embeddings tend to be higher-dimensional vectors so how can we meaningfully visualize them? There are two common dimensionality-reduction techniques: (i) principal component analysis (PCA) and (ii) t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Estimation (t-SNE). The intuition behind PCA is to repeatedly project along the dimension with the highest variance (since it has higher discriminative power) using a linear algebra technique such as singular value decomposition (SVD) until we hit the target dimension. t-SNE solves an optimization problem that tries to project the data such that the distances in the higher-dimensional space are similar to distances in the lower-dimensional space, thus locally preserving the structure of the higher-dimensional space in the lower-dimensional space. Both are good techniques to lower the dimensionality of the embedding so we can visualize words as points on a plane (while still preserving their semantics).

Fortunately, Scikit provides implementations for both so we can plot them side-by-side and see the differences.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

words_to_plot = ["king", "man", "queen", "woman", "egg", "chicken", "frog", "snake"]

embeddings_to_plot = np.array([e[word] for word in words_to_plot])

pca = PCA(n_components=2)

reduced_embeddings_pca = pca.fit_transform(embeddings_to_plot)

tsne = TSNE(n_components=2, random_state=42, perplexity=5)

reduced_embeddings_tsne = tsne.fit_transform(embeddings_to_plot)

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

# PCA on the left

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

plt.scatter(reduced_embeddings_pca[:, 0], reduced_embeddings_pca[:, 1])

for i, word in enumerate(words_to_plot):

plt.annotate(word, (reduced_embeddings_pca[i, 0], reduced_embeddings_pca[i, 1]))

plt.title('PCA Projection')

plt.xlabel('Principal Component 1')

plt.ylabel('Principal Component 2')

# t-SNE on the right

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.scatter(reduced_embeddings_tsne[:, 0], reduced_embeddings_tsne[:, 1])

for i, word in enumerate(words_to_plot):

plt.annotate(word, (reduced_embeddings_tsne[i, 0], reduced_embeddings_tsne[i, 1]))

plt.title('t-SNE Projection')

plt.xlabel('t-SNE Component 1')

plt.ylabel('t-SNE Component 2')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

The resulting plot shows that the vector difference between “king” and “man” is roughly the same as that of “queen” and “woman” in both plots! In the t-SNE plot, however, we see that the vectors are a bit closer in terms of magnitude and direction.

Some other interesting observations is with the other words: we see that snake and frog are closer together than say, man and egg because while they’re not synonyms, they’re still related words (both being animals that lay eggs). Try plotting other words to see how they cluster together in the lower-dimensional space!

Conclusion

Embeddings are a word representation that preserves semantic properties of words, such as relations to other words and connotation, in a much better way than representing words as strings of characters. Representing documents as vectors is counter-intuitively more straightforward so we started with learning about term frequency and document frequency; that also helped illustrate some interesting concepts like how words that occur too frequently should be downweighted since they don’t have discriminative power. To transition to representing individual words as embeddings, we learned about the distributional hypothesis that stated the meaning of a word depends on the context around it. Our first word embedding model word2vec trained embeddings with that in mind: train a model to predict if a word lies in the context window of a target word. Our next embedding model did a bit better by also looking at global word-word co-occurrences in addition to the local context window approach that word2vec uses. The final embedding model we discussed was a more recent type of model where we learn the embeddings from scratch as part of the language modeling task in an end-to-end fashion. Finally, we used embeddings to show how they can model semantic relations using word analogies as an example semantic understanding task.

Now that we have a vectorized format for embeddings, we can use them for different kinds of language models, the most popular and accurate ones being neural network language models, which we’ll cover next time 🙂