Lie Groups - Part 1

In this post, I want to discuss Lie Groups. For engineers or beginning physicists, Lie Groups might not be as familiar as multivariable calculus or linear algebra, but, in many regards, they’re a combination of both. Like with other topics in advanced mathematics, I like to apply them to solve some kind of real problem in engineering or physics. In this case, we’ll be looking at a problem I described in one of my previous posts: robotic state estimation. Given a position and orientation of a mobile robot, if we receive some new sensor data, we want to update both to account for those new sensor measurements. The tricky part is the orientation: we often represent it as a quaternion or rotation matrix and these are constrained, i.e., not just any ordinary matrix is a rotation matrix. We want to make sure the orientation update still obeys those constraints else we won’t have a valid orientation!

There are a lot of really good resources out there to learn about Lie Groups, particularly from physics. However, I think most of them lack an initial motivation: they jump right into a definition without giving any concrete examples. The closest I’ve found is Dr. Joan Solà’s work: A micro Lie theory for state estimation in robotics, which I think does a really good job at explaining the topic practically. It has concrete examples along with proofs and derivations; it starts with just talking about group structure and then adds calculus later on instead of conflating the two at the beginning. But there were many things I had to look up or do by hand when I was going through it to fill knowledge and really understand the proofs. Nevertheless, I still really like that work and used it as one of my references when writing this series on Lie Groups; the structure of this series and some of the examples are inspired from that work (especially when we get to caclulus on Lie Groups).

Lie Groups are a bit more theory-oriented that other kinds of maths, especially for engineers. It could be argued that you could go your entire engineering or (undergrad-level) physics career without ever using Lie Groups. This is partly true, but, for robotic state estimation, we’ll see why we can get a better result (rather than an approximate/error-filled one) if we’re aware about the structure of our problem.

As a meta-point, I’m breaking this up into two parts: this is the introductory part without any (or much) calculus and the next part will intersect calculus and Lie Groups to construct Jacobians and other structures.

2D Rotations

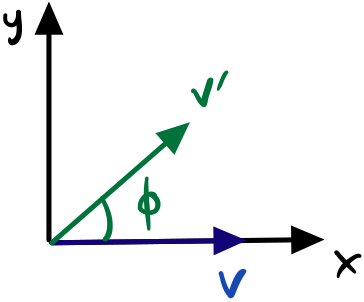

Let’s start with the simple example of a vector on a plane. This could be the position and orientation of a robot. Suppose we get some new sensor update that says our robot has rotated by some amount $\phi$ and we want to rotate the vector by that amount.

We have the $x$ basis vector $v$ that we want to rotate by some $\phi$ to get $v’$.

How would we go about doing this? We need an way to transform the initial vector $v=(x,y)^T$ into the rotated vector $v’=(x’,y’)^T$. Since we’re dealing with a vector in a plane, we can do this using ordinary geometry if we draw some angles and remember some trig formulas. Without going through the trig, we end up with the following way to relate $v’$ and $v$.

\[\begin{align*} x' &= x \cos\phi - y\sin\phi\\ y' &= y \cos\phi + x\sin\phi\\ \end{align*}\]For convenience, we can write this in matrix form.

\[\begin{align*} \begin{bmatrix}x'\\y'\end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix}\cos\phi & - \sin\phi \\ \sin\phi & \cos\phi\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\end{bmatrix}\\ v' &= R(\phi) v \end{align*}\]$R(\phi)\in\R^{2\times 2}$ is the 2D rotation matrix. Of course, we can plug in some known values and see if we get what we expect. Try plugging in $\phi=\frac{\pi}{2}$ and $(1,0)^T$, i.e., the $x$ basis vector, and the result should be $(0,1)^T$, i.e., the $y$ basis vector. We’ve basically rotate the $x$ basis vector into the $y$ basis vector!

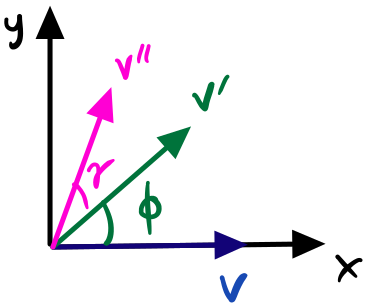

Suppose we have $v’$ that is $v$ rotated by $\phi$, and we rotate $v’$ again by $\gamma$ to get $v’’$.

If we have another rotation by angle $\gamma$ that we want to apply after the rotation to $\phi$, we can first apply $R(\phi)$ and then $R(\gamma)$.

\[\begin{align*} \begin{bmatrix}x''\\y''\end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix}\cos\gamma & - \sin\gamma \\ \sin\gamma & \cos\gamma\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\cos\phi & - \sin\phi \\ \sin\phi & \cos\phi\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\end{bmatrix}\\ v'' &= R(\gamma) R(\phi) v \end{align*}\]Notice the ordering we apply the rotations: right to left. We can also combine the two matrices into a single one and, with some trig, we find that the result is also a rotation matrix!

\[\begin{align*} \begin{bmatrix}x''\\y''\end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix}\cos(\gamma+\phi) & - \sin(\gamma+\phi) \\ \sin(\gamma+\phi) & \cos(\gamma+\phi)\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\end{bmatrix}\\ v'' &= R(\gamma + \phi) v \end{align*}\]Natural to applying a rotation, what if we wanted to reverse/undo a rotation? For example, we wanted to backtrack an orientation, we have to undo the existing rotation. To undo a rotation $R(\phi)$, we need to supply a matrix such that, when composed with $R(\phi)$, we get the identify matrix $I$ because, when we multiply any vector by the identify matrix, we get the same vector out. Naturally, this is the inverse matrix $R(\phi)^{-1}$! However, matrix inverses aren’t free! We need to prove that a rotation matrix $R(\phi)$ has an inverse. In other words, we need to show it has a nonzero determinant, i.e., it is nonsingular. Let’s take the determinant of a general 2D rotation matrix $R(\phi)$:

\[\det\begin{bmatrix}\cos\phi & -\sin\phi \\ \sin\phi & \cos\phi\end{bmatrix}=\cos^2\phi + \sin^2\phi = 1\]Using the trig identity $\cos^2\phi + \sin^2\phi = 1$, we’ve shown that every 2D rotation matrix has an inverse! This makes intuitive sense beacuse there isn’t a value of $\phi$ that we couldn’t “undo” by rotating by the same amount in the opposite direction.

\[\begin{align*} \begin{bmatrix}x\\y\end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix}\cos\phi & - \sin\phi \\ \sin\phi & \cos\phi\end{bmatrix}^{-1}\begin{bmatrix}\cos\phi & - \sin\phi \\ \sin\phi & \cos\phi\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\end{bmatrix}\\ v &= R(\phi)^{-1}R(\phi) v\\ v &= Iv\\ v &= v \end{align*}\]We’ve also discovered an implicit rule here: multiplying any vector by the identity matrix $I=R(0)$ doesn’t change the vector at all.

Let’s take a second and recap what we’ve learned so far because, while it might not seem like it, we’ve learned a lot about how 2D rotations work.

- Rotating vectors is a linear transform because it’s just a matrix multiplication (any linear function/operation can be represented as a matrix that acts on a vector)

- We can compose multiple rotations by multiplying their rotation matrices together, and we get a valid rotation matrix as a result

- Since we’re using matrix multiplication, this composition is also associative, i.e., $[R(\theta)\cdot R(\phi)]\cdot R(\gamma)=R(\theta)\cdot [R(\phi)\cdot R(\gamma)]$

- The inverse for a 2D rotation matrix always exists and can reverse/undo a rotation

- The identity matrix doesn’t affect the vector in any way

This set of properties is so useful that we actually give them a name in mathematics: a group! Remember the topic of this series is about Lie Groups so we have to discuss groups! Now that we’ve demonstrated some properties of groups using 2D rotations, let’s generalize that into a formal definition of a group.

Groups

A group $(G, \circ)$ is a set $G$ and an operator $\circ$ such that any $X,Y,Z\in G$ obeys the following group axioms:

- Closure: $X\circ Y\in G$. Composing any two elements of the group gives us another element in the group.

- Identity: $E\circ X = X\circ E = X$. There exists an identity element $E$ that has no effect on any element in the group.

- Inverse: $X^{-1}\circ X = X\circ X^{-1} = E$. For every element in the group, there’s an inverse element that brings it back to the identity.

- Associativity: $(X\circ Y)\circ Z = X\circ (Y\circ Z)$. We can group any two compositions in the sequence of compositions and do those first.

One other thing we saw was the action of the group on a vector: we multiplied the rotation matrix by a vector to rotate the vector. The action of a group on another set $V$, e.g., 2D vectors, has to be defined for every group and set since each action can be applied differently. More formally, the group action $\cdot$ can be defined as $\cdot: G\times V\rightarrow V; (X,v)\mapsto X\cdot v$ and has the following properties:

- Identity: $E\cdot v=v$. Applying the identity element doesn’t change the input.

- Compatibility: $(X\circ Y)\cdot v = X\cdot (Y\cdot v)$. Applying a composition is the same as applying each element of the composition in sequence.

Now that we understand the axioms of a group, let’s phrase 2D rotations as a group: $G=\{\text{2D rotation matrices}\}$ and $\circ=\cdot$, i.e., matrix multiplication. To be a bit more specific, we showed earlier than all 2D rotation matrices have a determinant of exactly 1. This is why the set of all 2D rotation matrices is called $SO(2)$ for Special Orthogonal Group of 2 dimensions. What makes it special is the unit determinant. It’s a subgroup of the general Orthogonal Group $O(2)$, which is the set of orthogonal matrices, i.e., $R^T R=I=RR^T$. So we can more formally define $SO(2)=\{R\in\R^{2\times 2}\vert R^T R=I, \det R = 1\}$. Notice that the only time we make mention of the dimension is in how large the matrices are; more generally, we can define $SO(n)=\{R\in\R^{n\times n}\vert R^T R=I, \det R = 1\}$. We can verify that 2D rotation matrices are orthogonal with some more trig identities. We can also verify that all of the group axioms are satisfied for $SO(2)$.

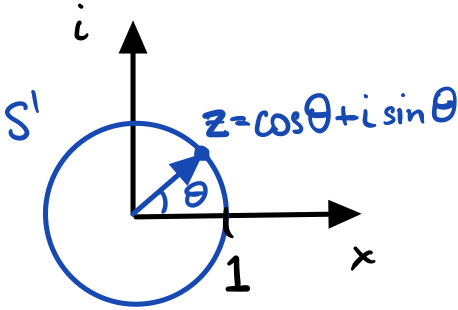

I’ll also take this opportunity to show another represenation of 2D rotations: unit-norm complex numbers: $z=\cos\theta + i\sin\theta$. These are also easier to visualize than rotation matrices since we can plot them on the complex plane. In fact, if we take all possible values of $\theta$ and plot all unit norm $z$ vectors on the complex plane, we get the unit circle $S^1$!

All of the possible rotations on a plane can be represented as the circle group $S^1$. A particular rotation $z=\cos\theta + i\sin\theta$ can be represented as a complex number that lives on that circle.

To develop this even further as a group, $G=S^1$ and $\circ=\cdot$, i.e., complex multiplication. If we have a 2D real vector (or just a complex number) represented as a complex number like $v=x+iy$ and a rotation $z=\cos\theta + i\sin\theta$, then we can rotate $v$ by $\theta$ by multiplying $v’=zv$. Notice that this is closed under multiplication, the identity element is 1, and the inverse is the complex conjugate $z^\star$.

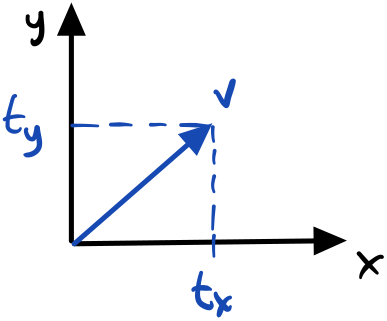

The translation group is an additive group that is simply $\R^n$.

As a more trivial example, consider the set of 2D translation $v=\displaystyle\begin{bmatrix}t_x\ t_y\end{bmatrix}^T\in\R^2=G$ and $\circ=+$. This is an example of an additive group. It’s closed under addition, the identity is 0, and the inverse is the negative $-t$.

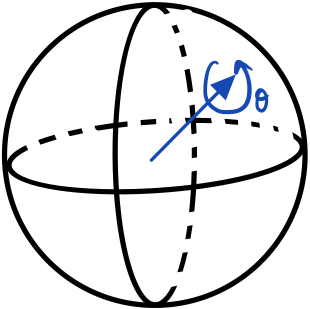

Quaternions can be represented as an axis and rotation about that axis. One way to visualize them is their effect on a basis vector or as an axis and rotation on the unit sphere.

As a less trivial example, consider the set of unit quaternions $S^3$ (a 3-sphere/hypersphere). They are a representation of 3D rotations $SO(3)$. Another way to think about quaternions is using the “axis-angle” formulation where we have an axis $\mathbf{u}=u_x i + u_y j + u_z k$ (where $i,j,k$ are the base/unit quaternions such that $i^2=j^2=k^2=ijk=-1$) that represents the vector we’re rotating around and an angle $\theta$ that we’re rotating by. We put both of them together into a single object: $\mathbf{q}=\cos\frac{\theta}{2}+\mathbf{u}\sin\frac{\theta}{2}$. (We’ll see a derivation of this later.) The reason we need an $i,j,k$ is because they obey a special relation that makes rotating vectors actually work. The group action is quaternion/complex multiplication. Acting a quaternion on a vector $\mathbf{v}= v_xi+v_yj+v_zk$ uses the double product $\mathbf{q}\mathbf{v}\mathbf{q}^\star$. It’s closed under that double product, the identity is 1, and the inverse is the complex conjugate $\mathbf{q}^\star$.

Manifolds

Going back to the problem of robotic state estimation, we generally have a state that includes some orientation, for example, in 3D space. We receive sensor updates and accumulate that orientation. For example, Kalman Filters do this by literally adding up increments in the state over some time interval. Other kinds of state estimation use numerical optimization to solve for the state history so it can be corrected later after we learn more information. This generally takes an objective function $C(x)$ that minimizes the sum of squared errors, computes a derivative (Jacobian) $\frac{\d C}{\d x_i}\vert_{x_i=\hat{x_i}}$ for the current values of the parameters $\hat{x}$, and applies a tiny update $\Delta x$ to get new parameters. The cycle repeats until we’ve found the minimum of the function.

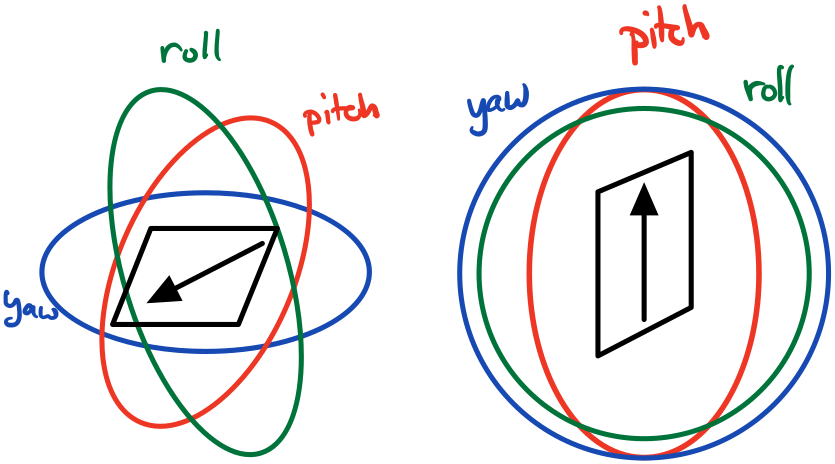

In a normal scenario, all three of the gimbals have all three degrees of freedom. However, during Gimbal Lock, we lose a degree of freedom because motions along two degrees of freedom only correspond to one motion.

For representing orientations in 3D, one option is to use Euler angles where we define an angle for roll, pitch, and yaw. This creates a vector in 3D space with exactly the same degrees of freedom as a 3D rotation. There’s nothing wrong with using Euler angles as a way to represent 3D rotation, however, we run into problems when we try to use them for optimization or accumulation. This is because of a problem called Gimbal Lock where we lose a degree of freedom, i.e., changing two variables leads to the same rotation. (More formally, we can think of Euler angles as a mapping of $\R^3$ into the set of 3D rotations $SO(3)$, but the derivative of this mapping isn’t always full-rank.)

However, we can avoid the problem of gimbal lock by using quaternions. But remember we’re not using just any quaternions, we using unit quaternions to represent 3D rotations. A general quaternion is $\mathbf{q}=\cos\frac{\theta}{2}+\mathbf{u}\sin\frac{\theta}{2}$ such that $\mathbf{u}=u_x i + u_y j + u_z k$, so we have 4 degrees of freedom $(\theta, u_x, u_y, u_z)$. But unit quaternions have the additional constraint of unit norm $\vert\vert\mathbf{q}\vert\vert=1$, which removes a degree of freedom (if we knew the values of 3 degrees of freedom, we could use the unit-norm equation to solve for the remaining one). So instead of a full 4D space, we actually have a constrained 3D surface in 4D, which is partly why unit quaternions are called $S^3$: they have 3 degrees of freedom! As an analogy, think about the unit circle $S^1$ for $SO(2)$. The unit circle is a 1D curve embedded in 2D governed by $x^2+y^2=1$: given either $x$ or $y$, we can compute the other using that equation. In other words, it’s a subspace embedded in a higher-dimensional space. Every point on that surface satisfies the constraint and any point off of that surface doesn’t.

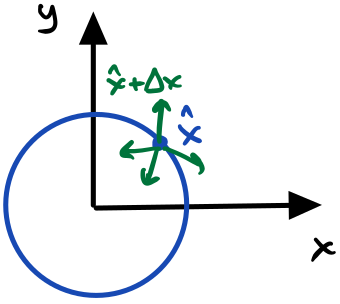

If our optimizer sees all degrees of freedom for $S^1$, then we’ll get an update for both $x$ and $y$ that can move us off the circle.

But does our optimizer know that? Unconstrained optimization, by definition, is unconstrained! (In general, unconstrained optimization is easier than constrained optimization and have had more practical success.) If we hand the full quaternion to the optimizer, it’ll see all degrees of freedom so produce an tiny update for each parameter. If we simply fold in that increment, then we’ll almost always end up off of the constrained surface. In other words, we’d end up with something that isn’t a unit quaternion and hence isn’t a 3D rotation. Before the next step of optimization, we’d have to “project” or “renormalize” it back into a unit quaternion, which induces some error!

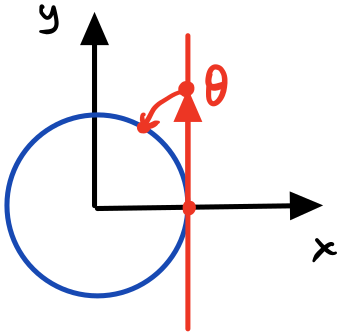

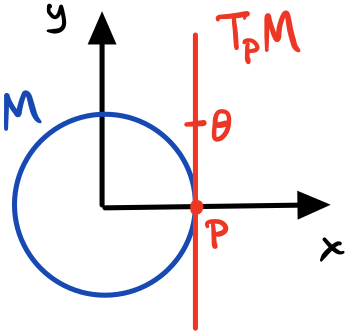

If we look at a line tangent to the sphere, we can define an increment $\theta$ on that line and find a way to project that onto the circle.

Instead, what if we parameterized the constrained surface in a way that we only handed the optimizer the exact degrees of freedom it could actually optimize over. Consider 2D rotations $SO(2)$ and $S^1$. For rotations on a plane, we really only need a single variable $\theta$ instead of two numbers for the complex representation or four for the rotation matrix. We could hand the optimizer the single $\theta$ and project that angle onto the unit circle.

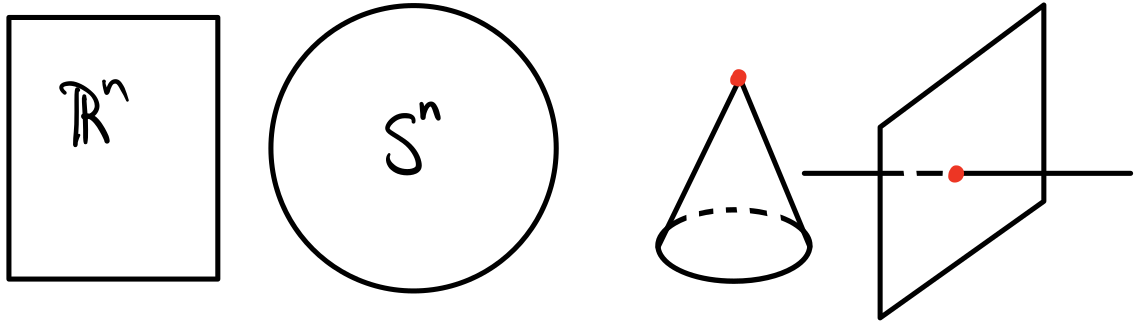

Examples of manifolds are $\R^n$ and $S^n$: they’re locally flat at a point. Examples of spaces that aren’t manifolds are cones and planes with lines through them because the tip of the cone and the point where the line intersects the plane aren’t locally flat.

As it turns out, there already exists a mathematical structure that encodes exactly what we’re trying to do: a manifold. Manifolds are complicated structures in their own right, and I actually have another series explaining them in detail (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3) so I won’t go over them again. Feel free to read those posts to understand their construction, but I’ll just give the more basic intuition here. A manifold is a space that is required to be flat locally but not globally. Some examples are $\R^n$: it’s both locally flat and globally flat! Another well-known example is the sphere $S^2$. At a point, a sphere is flat (in other words $\R^2$), but globally, it’s not flat; in fact, it has intrinsic curvature. A few examples of spaces that aren’t manifolds are cones or a plane with a line going through it. This is because the point of a cone and the point where the line intersects the plane are not locally flat. Similar to a circle, a sphere is another example of a constrained surface: we only need two coordinates to specify a point on a sphere, but it can be embedded in a 3D space.

Tangent Spaces

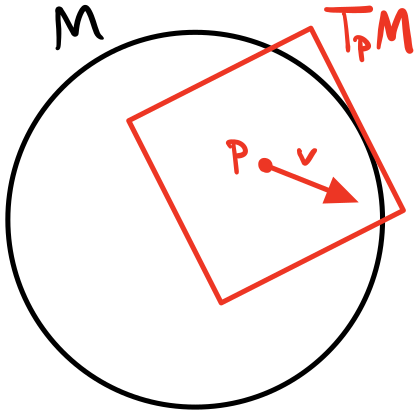

In general, the most interesting manifolds are smooth, i.e., continuous and infinitely differentiable. Going back to the example of a circle, if we took a derivative at a point, we’d get a tangent line with one degree of freedom. Specifically, if we consider the circle in the complex plane and took a derivative at $\theta=0$, we’d get the complex line $i\R$ which has one degree of freedom and is a flat space. Another name for this is the Tangent Space at a point $T_p M$. One way to intuitively construct it is by considering some curve on the manifold $\lambda(t) : \R\to M$ (in the case of the cirlce, it’s the circle itself!) and taking a derivative $\frac{\d}{\d t}$. (I discuss a more formal way to construct this in my other post on manifolds.) The tangent space has a few properties as a result of its construction:

- it exists uniquely at all points $p$

- the degrees of freedom of the tangent space is the same as the manifold

- the tangent space has the same structure at every point

In the context of Lie Groups, another name for the tangent space is the Lie Algebra $\mathfrak{m} = T_E M$. We specifically call the Lie Algebra the tangent space at the identity $E$ only because every Lie Group, by definition, is guaranteed to have an identity element. Remember that the structure of tangent space is the same at all points on the manifold so it really doesn’t matter which point we pick, but the identity is the most convenient element that every Lie Group is guaranteed to have.

More formally, we can define a tangent space $T_p M$ at a point $p$ on a manifold $M$ as the set of all directional derivatives of all scalar functions through $p$.

Ideally, we want the optimizer to only operate in the tangent space since it has exactly the same degrees of freedom as the manifold itself. Before talking about how the optimizer would do this, let’s see a few examples of tangent spaces.

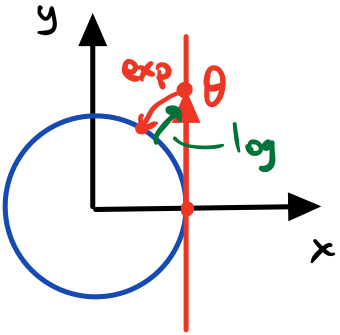

For the circle group $S^1$, the tangent space $T_E M$ is a line $i\R$ and elements of that tangent space are scalars $\theta\in i\R=T_E M$.

Let’s explore the tangent space of 2D rotation $SO(2)$. To do this, we need to identify a curve on the circle that we can take the derivative of. We can use the fact that all rotation matrices have the constraint that $R^T R = I$, i.e., orthogonal columns. We can replace the $R$s with parameterized curves $R(t)$ to get $R(t)^T R(t) = I$ and take the derivative $\frac{\d}{\d t}$.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\d}{\d t}[R(t)^T R(t)] &= \frac{\d}{\d t} I\\ R(t)^T \frac{\d}{\d t} R(t) + \frac{\d}{\d t}[R(t)^T] R(t) &= 0\\ R(t)^T \frac{\d}{\d t} R(t) + \left(\frac{\d}{\d t}R(t)\right)^T R(t) &= 0\\ R(t)^T \frac{\d}{\d t} R(t) &= -\left(\frac{\d}{\d t}R(t)\right)^T R(t)\\ R(t)^T \frac{\d}{\d t} R(t) &= -\left(R(t)^T \frac{\d}{\d t} R(t)\right)^T\\ A &= -A^T\\ \end{align*}\]Between the first and second lines, we use the product rule to expand the product. Then we use the property that derivatives can move in and out of the transpose operation. We moved the second term to the right-hand side. Finally, we transpose the right-hand side so that we end up with an equation of the form $A=-A^T$. If we removed the minus sign, this would be the constraint for a symmetric matrix $A=A^T$! But since we have the minus sign, we call matrices that obey this constraint skew-symmetric matrices. By the way, nothing we’ve done so far has been specific to $SO(2)$: as it turns out, this is the same constraint for $SO(3)$ and even $SO(n)$ as well. But going back to $SO(2)$, we’ve found that the Lie Algebra/structure of the tangent space, called $\mathfrak{so}(2)$, is the set of $2\times 2$ skew-symmetric matrices.

The general form for $2\times 2$ skew-symmetric matrices looks like

\[\begin{bmatrix}0 & -\theta \\ \theta & 0\end{bmatrix}=\theta\begin{bmatrix}0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}=\theta E_\theta\in\mathfrak{so}(2)\]We call $E_\theta$ the generator of the $\mathfrak{so}(2)$ because we can write every element in terms of $E_\theta$. Think of it as a “basis matrix”. From this formulation, we can take any $\theta\in\R$ and map it to $\theta E_\theta\in\mathfrak{so}(2)$ uniquely. This means that there’s a unique mapping between $\R$ and $\mathfrak{so}(2)$ so we can choose to use either space, whichever is convenient for us. For the optimizer, it would be most convenient to use the $\theta\in\R$ space. We can create a notation $[\theta]_\times$ to define this mapping as

\[[\cdot]_\times : \R\to\mathfrak{so}(2);~\theta\mapsto\begin{bmatrix}0 & -\theta \\ \theta & 0\end{bmatrix}\]With $SO(3)$, we can follow the exact same procedure to end up with the set of $3\times 3$ skew-symmetric matrices for its Lie Algebra $\mathfrak{so}(3)$. The general form of those looks like

\[\begin{align*} \begin{bmatrix}0 & -\omega_z & \omega_y \\ \omega_z & 0 & -\omega_x \\ -\omega_y & \omega_x & 0\end{bmatrix}&=\omega_x\begin{bmatrix}0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}+\omega_y\begin{bmatrix}0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}+\omega_z\begin{bmatrix}0 & -1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}\\ &=\omega_x E_x+\omega_y E_y+\omega_z E_z \end{align*}\]Note that we have 3 degrees of freedom $\omega_x, \omega_y, \omega_z$ and thus 3 generators $E_x, E_y, E_z$. So instead of just $\R$, the degrees of freedom can be grouped into a vector $\omega=[\omega_x, \omega_y, \omega_z]^T\in\R^3$. Just like with $\mathfrak{so}(2)$ and $\R$, the degrees of freedom match the dimension of the flat space. We reuse the same notation to denote converting a vector $\omega\in\R^3$ into a skew-symmetric matrix in $\mathfrak{so}(3)$: $[\omega]_\times$.

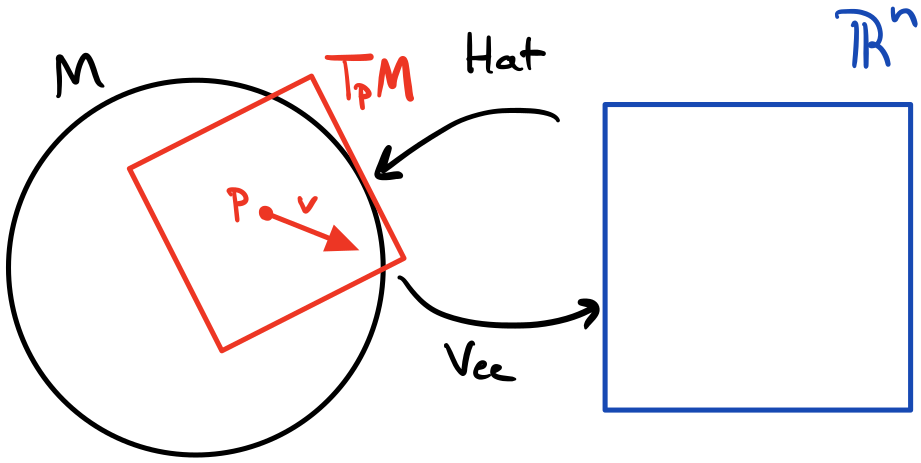

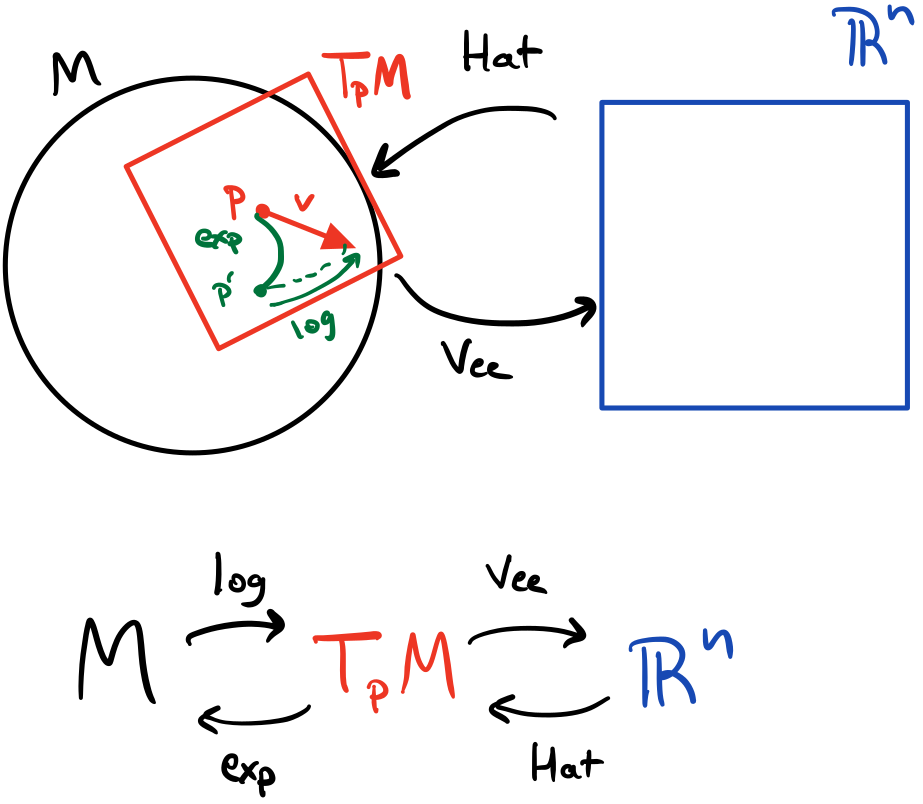

Between the tangent space $T_E M=\mathfrak{m}$ and flat space $\R^n$, we can define isomorphisms that exactly map between the two spaces.

In general, not all Lie Algebras are skew-symmetric matrices, but we can define an isomorphism, i.e., a bijection/one-to-one correspondence, that maps between $\mathfrak{m}\leftrightarrow \R^n$.

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{Hat} : \R^n\to\mathfrak{m} &;~v\mapsto v^\wedge\\ \mathrm{Vee} : \mathfrak{m}\to \R^n &;~v^\wedge\mapsto (v^\wedge)^\vee=v \end{align*}\]In other words, $v$ is some element in a flat space $\R^n$ and $v^\wedge$ is some element of the Lie Algebra. As an example, for $SO(2)$ and $\mathfrak{so}(2)$, we can define these operators in terms of $[\cdot]_\times$.

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{Hat}: \R\to\mathfrak{so}(2) &;~\theta\mapsto \theta^\wedge = [\theta]_\times\\ \mathrm{Vee}: \mathfrak{so}(2)\to \R &;~[\theta]_\times \mapsto [\theta]^\vee_\times=\theta \end{align*}\]For $SO(3)$ and $\mathfrak{so}(3)$, we can define the same kinds of operators, except using $\R^3$ and $\mathfrak{so}(3)$.

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{Hat}: \R^3\to\mathfrak{so}(3) &;~\omega\mapsto \omega^\wedge = [\omega]_\times\\ \mathrm{Vee}: \mathfrak{so}(3)\to \R^3 &;~[\omega]_\times \mapsto [\omega]^\vee_\times=\omega \end{align*}\]With these functions, we now have a way to map our degree-of-freedom flat space $\R^n$ into the tangent space/Lie Algebra of the particular Lie Group we’re working with. In the case of 2D rotations, we only have a single degree of freedom $\theta$ that we can project out into the Lie Algebra of $2\times 2$ skew-symmetric matrices. However, we’re still missing a way to project the Lie Algebra onto the Lie Group manifold. Let’s figure out how (and why).

The Exponential Map

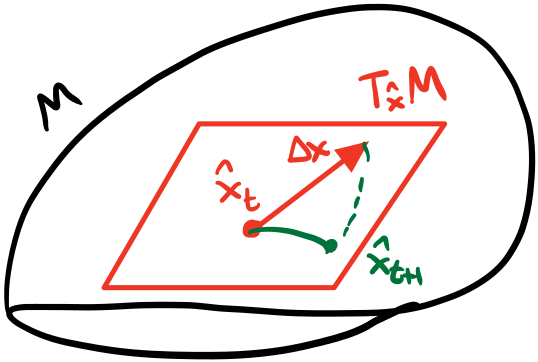

Recall that our problem with state estimation was that our representations for orientation were either overparameterized (quaternions or rotation matrices) or not suitable for optimization/integration (Euler angles). However, learning about manifolds and the tangent space, we can let our optimizer move around in the tangent space where we have the same degrees of freedom as the manifold: no more, no less. After the optimizer computes the derivatives, we get some gradient vector $\Delta x\in\R^n$ that represents the tiny update for all of our parameters. Since we’re at some point $\hat{x}$ on the manifold, this update $\Delta x$ is in the tangent space!

At any stage of optimization, we have the current values of the parameters $\hat{x}$. Giving that to our optimizer along with the Jacobians, we’ll get some $\Delta x$ for all parameters that lives in the tangent space $T_\hat{x} M$. We can’t blindly apply the update so we want to project that onto the manifold $M$.

To get the next value of the parameters, we need to add/accumulate $\Delta x$ into $\hat{x}$. What we’d do is just add $\hat{x}+\Delta x$, which almost certainly puts it off the constrained surface, and “reproject” it back onto the manifold so that the solution obeys the constraints. Rinse and repeat until we converge. The problem is that the “reprojection” induces some error. Ideally, we want to perform this mapping from $\mathfrak{m}\to M$ exactly, without any error. Then, after we get a parameter update $\Delta x$, we can apply that mapping and get the next value of the parameters that are guaranteed to obey the constraints, i.e., they remain on the manifold.

In other words, given some vector $v$ or $v^\wedge\in T_p M$, we want to relate it to some $X\in M$. If we consider rotation groups and go back to the definition of the Lie Algebra: $R(t)^T \frac{\d}{\d t}R(t)=\omega^\wedge=R(t)^{-1} \frac{\d}{\d t}R(t)$ (for orthogonal matrices, $R^T=R^{-1}$), then we have an equation relating an element of the Lie Algebra $\omega^\wedge$ and an element of the Lie Group $R(t)$. Isolating $\frac{\d}{\d t}R(t)$ to one side, we get the differential equation:

\[\frac{\d}{\d t}R(t) = R(t)\omega^\wedge\]This is an ordinary differential equation in $t$ whose solution is well-known (if you took a differential equations class, this was probably the first solution you saw):

\[R(t) = R(0)\exp(\omega^\wedge t)\]Since $R(t)\in M$ and $R(0)\in M$, then $\exp(\omega^\wedge t)\in M$. Since the structure of the tangent space is the same at all points, we can actually set $R(0)=E=I$ to get $R(t)=\exp(\omega^\wedge t)$. So it seems the way to relate a $\omega^\wedge\in T_p M$ and $R(t)$ is via $\exp$. We call this the exponential map: a function that sends elements of $\mathfrak{m}$ to $M$ exactly, with no error or approximation (i.e., the solution to the differential equation is analytical). Naturally, we can reverse the operation by taking a $\log$ and can define the logarithmic map as a function that maps $M$ to $\mathfrak{m}$ exactly.

\[\begin{align*} \exp: \mathfrak{m}\to M &; v^\wedge\mapsto X=\exp(v^\wedge)\\ \log: M\to\mathfrak{m} &; X\mapsto v^\wedge=\log(X) \end{align*}\]Intuitively, we can think of these maps as “wrapping” and “unwrapping” the vector along the manifold. To be more precise, this creates a geodesic at $p$ whose tangent vector is $v$. A geodesic is a generalization of a “straight line” or “shortest distance” path on a manifold. In $\R^n$, geodesics are lines. However, on other kinds of manifold, these are generally not lines. For example, for the sphere $S^2$, geodesics are “great circles”: a circle on the sphere such that the center of the circle is the center of the sphere. This is because “straight lines” don’t generally exist on arbitrary manifolds so we have to compromise and pick the “straight as possible” line. The formal way to derive geodesics is to use calculus of variations and solve for the function that minimzes the distance between two points on the manifold given the manifold metric. We’re not going to do that here, but look at my other series on manifolds for more intuition.

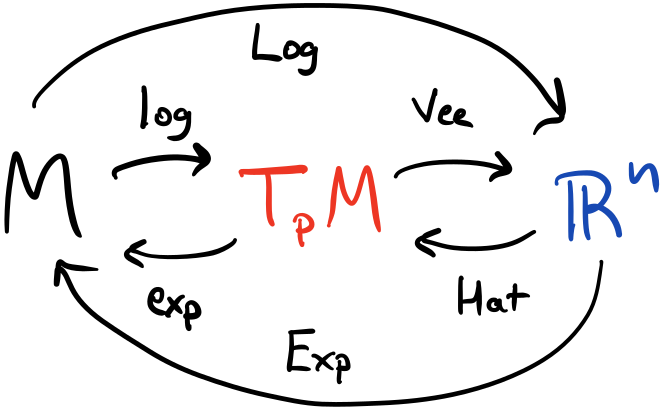

Now that we’ve defined the exponential and logarithmic maps, we have the full picture where we can convert between the flat space $\R^n$, the Lie Algebra/tangent space $T_p M=\mathfrak{m}$, and the manifold $M$.

Let’s look at a few concrete examples of the exponential map starting with $SO(2)$. Recall that all $2\times 2$ skew-symmetric matrices are of the form

\[\begin{bmatrix}0 & -\theta \\ \theta & 0\end{bmatrix} = \theta E_\theta\]Applying the exponential map:

\[\exp\left(\begin{bmatrix}0 & -\theta \\ \theta & 0\end{bmatrix}\right) = \exp(\theta E_\theta)\]But what does it mean to take the exponential of a matrix? Remember that $\exp$ can be written as a Taylor series!

\[\exp(x) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty\frac{x^k}{n!}=1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+\frac{x^3}{3!}+\cdots\]We can take powers of square matrices so the matrix exponential is well-defined. Expanding it out we get:

\[\exp(\theta E_\theta) = I+\theta E_\theta+\frac{\theta^2}{2!}E_\theta^2+\frac{\theta^3}{3!}E_\theta^3+\cdots\]To expand this further, we need to compute matrix products $E_\theta^k$. Let’s start by computing the first two:

\[\begin{align*} E_\theta &= \begin{bmatrix}0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\\ E_\theta^2 &= \begin{bmatrix}0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\\ \end{align*}\]An interesting property of skew-symmetric matrices is that the powers are cyclic and we actually only need $E_\theta$ and $E_\theta^2$. Here’s the pattern:

\[\begin{align*} E_\theta^0 &= I&\\ E_\theta^1 &= E_\theta & E_\theta^2 &= E_\theta^2\\ E_\theta^3 &= -E_\theta & E_\theta^4 &= -E_\theta^2\\ E_\theta^5 &= E_\theta&\\ \cdots \end{align*}\]Applying this cycling to the Taylor series, we get:

\[\begin{align*} \exp(\theta E_\theta) &= I+\theta E_\theta+\frac{\theta^2}{2!}E_\theta^2-\frac{\theta^3}{3!}E_\theta-\frac{\theta^4}{4!}E_\theta^2+\cdots\\ &= I+E_\theta\left(\theta-\frac{\theta^3}{3!}+\frac{\theta^5}{5!}+\cdots\right) + E_\theta^2\left(\frac{\theta^2}{2!}-\frac{\theta^4}{4!}+\cdots\right)\\ &= I + E_\theta\sin\theta + E_\theta^2(1-\cos\theta)\\ &=\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix}0 & -\sin\theta\\ \sin\theta & 0\end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix}\cos\theta-1 & 0\\ 0 & \cos\theta-1\end{bmatrix}\\ &=\begin{bmatrix}\cos\theta & -\sin\theta\\ \sin\theta & \cos\theta\end{bmatrix} \end{align*}\]In the first step, we’ve regrouped the terms by $E_\theta$ and $E_\theta^2$. Then we notice that the two series are actually convergent Taylor series for $\sin\theta$ and $1-\cos\theta$. This is the general strategy when dealing with Taylor series: expand it out, regroup the terms, and condense it using other known Taylor series. After that, we can expand $I$, $E_\theta$, and $E_\theta^2$ into matrices and solve for the end result and get a 2D rotation matrix! So the exponential map for $SO(2)$ maps a scalar $\theta\in\R$ into a 2D rotation matrix $R\in SO(2)$!

For the circle group $S^1$, the exponential map exactly sends and element in the tangent space to an element in the group. The logarithmic map does the opposite: it maps an element of the group into a tangent space at a point.

For $SO(3)$, The procedure is almost exactly the same, except we parameterize the input as an axis-angle representation $\theta[\omega]_\times$. Since $[\omega]_\times$ is also a skew-symmetric matrix, the same power cycling happens, and we actually end up with the same result.

\[\exp(\theta[\omega]_\times)=I+[\omega]_\times\sin\theta+[\omega]_\times^2(1-\cos\theta)\]This formula is so important that it’s actually called the Rodrigues Rotation Formula. As it turns out, quaternions have the same kind of result (except with a factor of 2 to account for the double product).

Using the isomorphisms and the $\exp$/$\log$ maps, we can exactly map between $M$, $T_p M$, and $\R$.

Note that all of these exponential maps are exact. There’s no approximation! We’re exactly condensing the infinite series using convergent Taylor series. Now that we’ve seen some concrete examples, we can use the same formula to derive a few properties (that I won’t prove directly).

\[\begin{align*} \exp((a+b)v^\wedge)&=\exp(av^\wedge)\exp(bv^\wedge)\\ \exp(av^\wedge)&=\exp(v^\wedge)^a\\ \exp(-v^\wedge)&=\exp(v^\wedge)^{-1}\\ \exp(X v^\wedge X^{-1}) &= X\exp(v^\wedge)X^{-1} \end{align*}\]As a shortcut, we can define $\Exp$ and $\Log$ operators that use $\exp$ and $\log$ and map directly between $\R$ and $M$.

\[\begin{align*} \Exp: \R^n\to M &; v\mapsto X=\Exp(v)\equiv\exp(v^\wedge)\\ \Log: M\to\R^n &; X\mapsto v=\Log(X)\equiv\log(X)^\vee \end{align*}\]

We can define shortcut isomorphisms $\Exp$/$\Log$ that map directly between $M$ and $\R$.

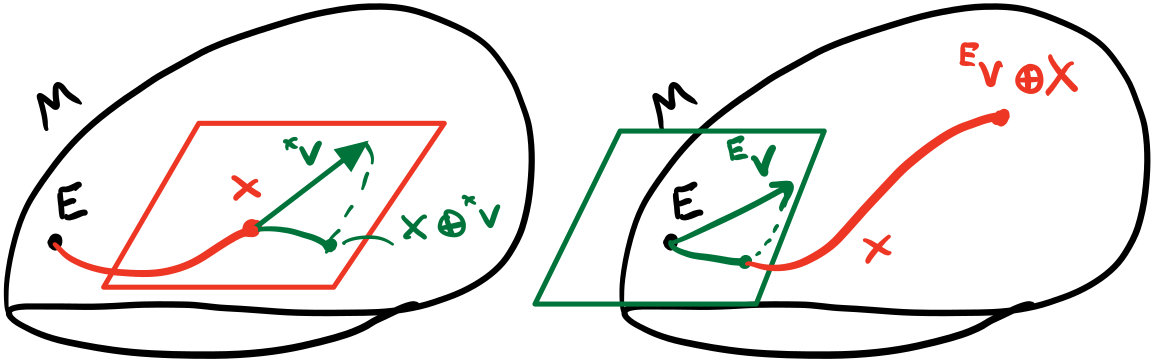

As another convenience, we can define $\oplus$ and $\ominus$ that use $\Exp$ and $\Log$ as well as group composition. But since not all group operations commute, we need to define left and right operations. We can define the right ones as:

\[\begin{align*} \oplus &: Y=X\oplus {}^X v\equiv X\Exp({}^Xv)\in M\\ \ominus &: {}^xv=Y\ominus X\equiv\Log(X^{-1}Y)\in T_X M\\ \end{align*}\]The left ones are defined as:

\[\begin{align*} \oplus &: Y={}^E v\oplus X\equiv \Exp({}^Ev)X\in M\\ \ominus &: {}^Ev=Y\ominus X\equiv\Log(YX^{-1})\in T_E M\\ \end{align*}\]

We can define additional shortcut notation to perform on-manifold “addition” and “subtraction”. Since not all group operations are commutative, we need two operations: one for left and one for right operations.

Note that the left and right $\oplus$ are distinguished by the order of the operations but $\ominus$ is ambiguous. Another thing to note is the left superscript: $E$ means the “global frame” while $X$ means the “local frame”. The structure of all $T_p M$ are identical so it really doesn’t matter what we call the global and local frames, but, since every Lie Group has an $E$, we decide on that for the consistent “global frame” and everything else is a “local frame”. The usefulness of this construct is that we can using the right $\oplus$ to define perturbations in the local frame: when our optimizer has a little update $\Delta x$, that happens in the local frame of the current set of parameters $\hat{x}$.

Motion Integration using Lie Groups

While there’s still (at least) a Part 2 to this series, we’ve covered enough to perform some motion integration or, at least, set up the problem. For robot state estimation in a 2D space, we have both a 2D translation as well as a rotation. The Lie Group corresponding to a combination of translations and rotations is called $SE(2)$, the Special Euclidean Group of 2 dimensions. This combines both translations and rotations so that all operations consider both, jointly; in other words, it’s the set of rigid motions in 2D.

\[X=\begin{bmatrix}R & t \\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\]where $R\in SO(2)$ and $t\in\R^2$. Just like with other Lie Groups, we can define the Lie Algebra and exponential maps for $SE(2)$ as well. In the context of state estimation, we start with some pose $X\in SE(2)$. At some fixed $\Delta t$, we get translational and rotation data from our sensors, e.g., the inertial measurement unit (IMU) and wheel encoders of our robot. If we integrate that, we get a small $\Delta t$ for the translation and $\Delta\theta$ for the angle. This exists in the Lie Algebra of $X$, i.e., the current pose we’re at. If we want to integrate that measurement to get a new pose, we need to use the exponential map to ensure that we have a valid rotation at each step.

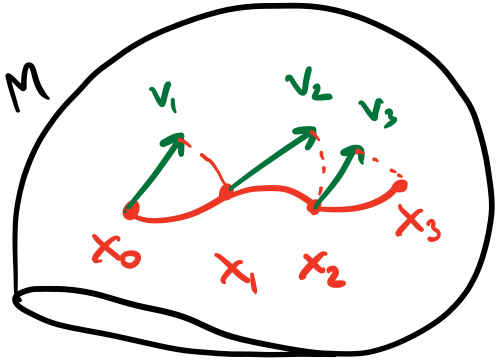

Starting at $X_0$, we receive a number of sensor measurements in that local frame and can incorporate that into our pose using the $\oplus$ operator for each sensor measurement.

Starting with $X$, we get some increment $v = \begin{bmatrix}\Delta t & \Delta\theta\end{bmatrix}^T\in T_X M$ across some time increment. To integrate it into the current pose, we use the $\oplus$ operator.

\[X_{i+1}=X_i\oplus v=X_i\Exp(v)\]This is a simple equation but builds on all of the things we’ve learned so far. If we had a sequence of these, we can fold them in through the group operation.

\[X_{i}=X_0\oplus v_1\oplus v_2\oplus\cdots \oplus v_i\]This allows us to take sensor measurements in the local frame and apply them exactly to the pose we’re at to get a new pose that obeys orientation constraints. The only thing we’re missing is the propagation of uncetainties as well. For most state estimation, in addition to the poses, we also have some estimate of uncertainty, either implicit or explicit. Using those uncertainties, however, requires us to perform calculus since we have to compute the Jacobian of the state propagation function, i.e., $\oplus$! We’ll get to that next time!

Conclusion

In this post, I introduced Lie Group using rotations. We first defined 2D rotation using just plain geometry. We used that intuition to define groups and their axioms. Then I gave the intuition about the other part of Lie Groups: manifolds. As a part of manifolds, we also constructed tangent spaces and saw how to map between the tangent space and its corresponding flat space. Beyond the tangent space, we defined the exponential map to map between the tangent space and the manifold itself. Finally, we saw how to apply our new way of thinking to motion integration.

Lie Groups are fairly more theoretical than other kinds of engineering work, and they do represent a different way of thinking about rotation. However, armed with this new knowledge, we can manipulate rotations and other Lie Groups in an error-free way. The other part that we have yet to cover is how to perform calculus on Lie Groups. The optimizer computes derivatives/Jacobians, after all. Just like with the exponential map, we want to stay in the tangent space because it has the same degrees of freedom as the manifold. We want to do the same thing with derivatives: compute variations solely in the tangent space. After we figure that out, we can really perform motion integration and optimization on the manifold. We’ll get to that in the next post! 😀