Neural Nets - Part 1: Perceptrons

In the past decade, neural networks have shown a huge spike in interest across industry and academia. Neural nets have actually existed for decades but only recently have we been able to efficiently train and use them due to advancements in software and hardware, especially GPU and GPU architecture. They’ve shown astounding performance across multitudes of tasks like image classification, object segmentation, text generation, speech synthesis, and more! While the exact details of these networks may be different, they are built from the same foundation, and many concepts and structures are common across all different kinds of neural nets.

In this post, we’ll start with the first and simplest kind of neural network: a perceptron. It models a single biological neuron and can actually be sufficient to solve certain problems, even with its simplicity! We’ll use perceptrons to learn how to separate a dataset and represent logic gates. Then we’ll extend perceptons by feeding them into each other to create multilayer perceptrons to separate even nonlinear datasets!

Biological Neurons

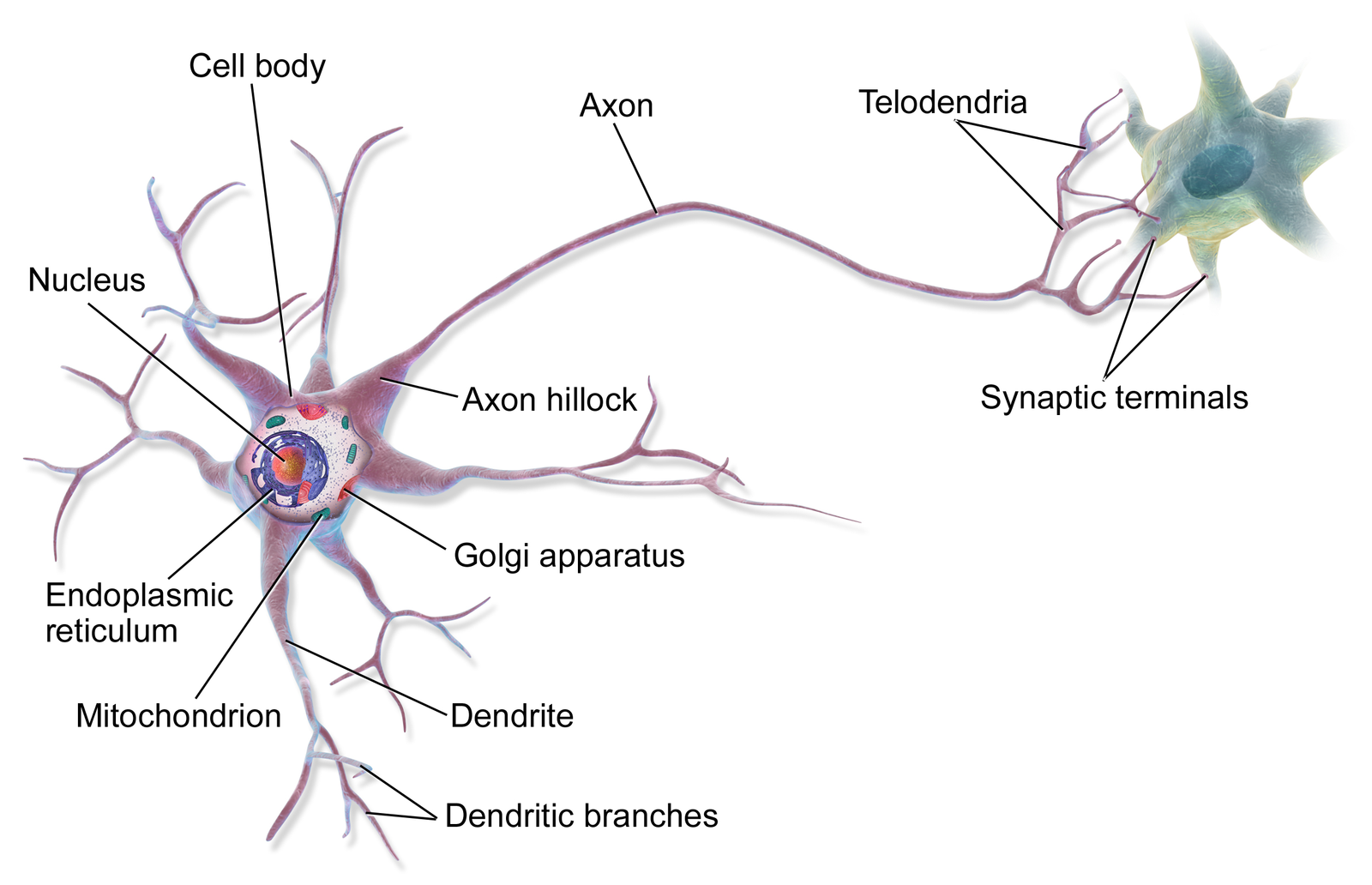

In the mid 20th century, there was a lot of work on trying to further artificial intelligence, and the general idea was to create artificial intelligence by trying to model actual intelligence, i.e., the brain. Looking towards nature and how it creates intelligence makes a lot of intuitive sense (e.g. dialysis treatment was the result of studying what kidneys to replicate their function). We know that the brain is comprised of biological neurons like this.

Source. A biological neuron has a cell body that accumulates neurotransmitters from its dendrites. If the neuron has enough of a charge, then it emits an electrical signal called an action potential through the axon. However, this signal is only produced if there is “enough” of a charge; if not, then no signal is produced.

(This wouldn’t be an “Intro to Neural Nets” explanation without a picture of an actual biological neuron!)

A few key conceptual notions of artificial neurons arose from this exact model and simplistic understanding. Specifically, a biological neuron has dendrites that collect neurotransmitters and sends them to the cell body (soma). If there is enough accumulated input, then the neuron fires an electrical signal through its axon, which connects to other dendrites through little gaps called synaptic terminals. There exists an All or Nothing Law in physiology where, when a nerve fiber such as a neuron fires, it produces the maximum-output response rather than any partial one (interestingly this was first shown with the electrical signals across heart muscles that keep the heart beating!); in other words, the output is effectively binary: either the neuron fires or it does not based on a threshold of accumulated neurotransmitters.

Trying to model this mathematically, it seems like we have some inputs $x_i$ (dendrites) that are accumulated and determine if a binary output $y$ fires if the combined input is above a threshold $\theta$. Since we have multiple inputs, we have to combine them somehow; the simplest thing to do would be to add them all together. This is called the pre-activation. Finally, we threshold on the pre-activation to get a binary output, i.e., apply the activation function to the pre-activation.

\[y=\begin{cases} 1, & \displaystyle\sum_i x_i \geq \theta \\ 0, & \displaystyle\sum_i x_i < \theta \\ \end{cases}\]What are the kinds of things we can model with this? For the simplest case, let’s consider binary inputs and start with binary models. For example, consider logic gates like AND and OR. If we chose the right value of $\theta$, we can recreate these gates using this neuron model. For an AND gate, the output is $1$ if and only if both inputs are $1$. $\theta = 2$ seems to be the right value to recreate an AND gate. For an OR gate, the output is $1$ if either of the inputs are $1$. $\theta=1$ seems to be the right value to recreate an OR gate. What about an XOR gate? This gate returns $1$ if exactly one of the inputs are $1$. What value of $\theta$ would allow us to recreate the XOR gate? We can try a bunch of different values but it turns out that there is no value of $\theta$ that can allow us to recreate the XOR gate under this particular mathematical model. One other way to see this is visually.

We can plot the inputs along two axes representing two inputs and color them based on what the result should be, i.e., white is output of 1 and black is output of 0. Note that the neuron model is a linear model which means we can only represent gates whose outputs are separable by a line. This is true for the AND and OR gates, but not for the XOR gate. However, two lines could be used the recreate the XOR gate so it seems like we’ll need a more expressive model.

We’ll see later what model we need to also be able to recreate the XOR gate, but it’s important to know that this simple model has limitations on its representative power so we’re going to need a more complicated model in the future.

Perceptrons

This seems like a good start but there’s no “learning” happening here. Even before neural networks, we had learning-based approaches that sought to solve (or optimize for) some parameters given an objective/cost/loss function and set of input data. For example, consider fitting a least-squares line to a set of points. Given some parameters of our model (specifically the slope and y-intercept) and a set of data (set of points to fit a line to), we want to find the optimal values of the parameters such that they “best” fit the data (according to the cost). In our example, we do have a single parameter $\theta$ parameter, but we’ve been guessing the value that works, which clearly won’t work for more complex examples.

One thing we can do to improve the expressive power is to add more parameters to the model and figure out how to solve/optimize for them given a set of input data rather than having to guess their values by inspection. There are an number of different ways to do this but one effective way is to introduce a set of weights $w_i$, one for each input, and a bias $b$ across all inputs. Since we have a single bias that can shift the values of the inputs, we can also simplify the activation function to fix $\theta=0$ and let the learned bias shift the input to the right place.

\[y=\begin{cases} 1 & \displaystyle\sum_i w_i x_i + b \geq 0 \\ 0 & \displaystyle\sum_i w_i x_i + b < 0 \\ \end{cases}\]This thresholding function is also called the Heaviside step function. A simpler notation is to collect the weights and inputs into vectors and use the dot product.

\[y=\begin{cases} 1 & w\cdot x + b \geq 0 \\ 0 & w\cdot x + b < 0 \\ \end{cases}\]Furthermore, we can absorb the bias into the weights and input by adding a dimension to the input and weight dimension and fixing the first value of every input to $1$ always. We can think of the bias as being a weight whose input is always $1$, i.e., $\sum_{i\neq 0} w_i\cdot x_i + b\cdot x_0$ where $x_0=1$.

\[y=\begin{cases} 1 & w\cdot x \geq 0 \\ 0 & w\cdot x < 0 \\ \end{cases}\]We’ll also sometimes use $y=f(w\cdot x)$ as a shorthand where $f$ represents the step function.

This very first neural model is called the perceptron: a linear binary classifier whose weights we can learn by providing it with a dataset of training examples and using the perceptron training algorithm to update the weights. Supposing we have the already-trained values of the weights, we can take any input, dot it with the learned weights, and run it through the step function to see which of the two classes the input belongs in.

One illustrative example to see how this is more general than the binary case is to recreate our logic gates, but using this model instead. Again, let’s try to recreate the AND and OR gates. Both of these take two inputs $x_1$ and $x_2$ so we’ll have $w_1$, $w_2$ and $b$ that we need to find appropriate values for.

Similar to the previous examples, we’ll recreate the AND and OR logic gates but use the weights of the perceptron rather than the threshold. The values of the weights are on the edges while the value of the bias term is inside of the neuron. Note that the perceptron model is a still a linear model so we still can’t represent the XOR gate just yet.

With some inspection and experimentation, we can figure out the values for the weights and bias. For the AND gate, if we set $w_1=1$, $w_2=1$, $b=-2$, then for the positive case, we get the input $x_1+x_2-2$. Only when both $x_1=x_2=1$ would the pre-activation be $0$ and hence produce $y=1$ after running through the step function. For the OR gate, the parameters are $w_1=1$, $w_2=1$, $b=-1$ and the input is $x_1+x_2-1$. There are also other gates we can represent, e.g., NOT and NAND, but still not XOR since perceptrons are still linear models. Note that the values of these parameters aren’t the only values that satisfy the criteria; this will become important much later on when we talk about regularization.

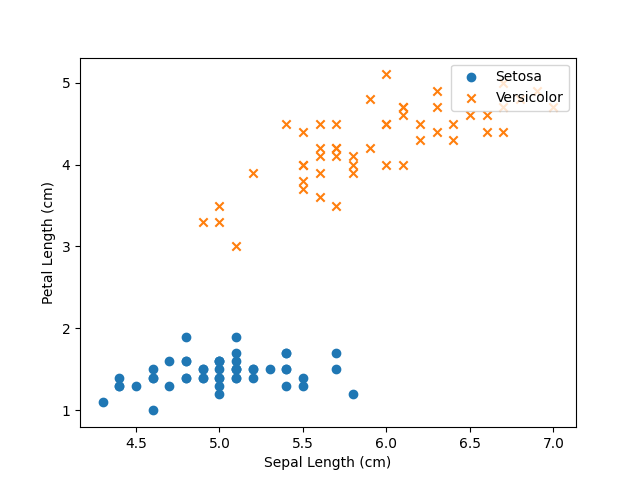

Similar to the previous cases, we’ve manually solved for the values of the parameters since there were only three and our “dataset” was one example but what if we wanted to separate a dataset like this.

These data are taken from a famous dataset called the Iris Flower dataset that measured the petal and sepal length and width of 3 species of iris flowers: iris setosa, iris versicolor, and iris virginica. Here, we plot only the sepal and petal lengths of iris setosa and iris versicolor. Notice that we can draw a line that separates these two species. Interestingly this dataset was collected by the God of statistics: Ronald Fisher.

Now trying to figure out the weights and bias by inspection becomes a bit more difficult! Now imagine doing the same for a 100-dimensional dataset. It’d be nigh impossible! These are the majority of practical cases we’ll encounter in the real world so we need an algorithm for automatically solving for the weights and bias of a perceptron. Let’s set up the problem: we have a bunch of linearly separable pairs of inputs $x_i$ and binary class labels $y_i\in\{0,1\}$ that we group into a dataset $\mathcal{D} = \Big\{ (x_1, y_1), \cdots, (x_N, y_N) \Big\}$ and we want to solve for the set of weights that correctly assigns the predicted class value $\hat{y} = f(w\cdot x)$ to the correct class value $y$ for examples in our dataset.

In other words, we want to update our weights using some rule such that we eventually correctly classify every example. The most general kind of weight update rule is of the form.

\[w_i\gets w_i + \Delta w_i\]For each example in the dataset, we can apply this rule to move the weights a little bit towards the right direction. But what should $\Delta w_i$ be? We can define a few desiderata of this rule and try to put something together. First, if the target and predicted outputs are the same, then we don’t want to update the weight, i.e., $\Delta w_i = 0$ since the model is already correct! However, if the target and predicted outputs are different, we want to move the weights towards the correct class of that misclassified example. One last important thing is to be able to scale the weight update so that we don’t make too large of an update and overshoot. Putting all of these together, we can come up with an update scheme like the following.

\[\Delta w_i = \alpha(y-\hat{y})x_i\]where $\alpha$ is the learning rate that controls the magnitude of the update. Note that when the target and predicted class are the same, $\Delta w_i = 0$ since we’re already correct. However, if they disagree, then we move the weights towards the direction of the correct class of that misclassified example.

Putting everything together, we have the Perceptron Training Algorithm!

Given a learning rate $\alpha$, set of weights $w_i$, and dataset $\mathcal{D} = \Big\{ (x_1, y_1), \cdots, (x_N, y_N) \Big\}$,

- Randomly initialize the weights somehow, e.g., $w_i\sim\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2_w)$ with some variance $\sigma^2_w$

- For each epoch

- For each training example $(x_j, y_j)$ in the dataset $\mathcal{D}$

- Run the input through the model to get a predicted class $\hat{y}_j = f(w\cdot x_j)$

- Update all weights using $w_i\gets w_i + \alpha(y_j-\hat{y}_j)x_j$

- For each training example $(x_j, y_j)$ in the dataset $\mathcal{D}$

An epoch is an full iteration where the network sees all of the training data exactly once; it’s used to control the high-level loop in case the perceptron or network doesn’t converge perfectly. That being said, this update algorithm is actually guaranteed to converge in a finite amount of time by the Perceptron Convergence Theorem. The proof itself isn’t particularly insightful but the existence of the proof is: with a linearly separable dataset, we’re guaranteed to converge after a finite number of mistakes.

Perceptrons are really easy to code up so let’s go ahead and write one really quickly in Python using numpy.

import numpy as np

class Perceptron:

def __init__(self, lr=0.01, num_epochs=10):

self.lr = lr

self.num_epochs = num_epochs

def train(self, X, y):

# initialize x_0 to be bias

self.w_ = np.zeros(1 + X.shape[1])

self.losses_ = []

for _ in range(self.num_epochs):

errors = 0

for x_i, y_i in zip(X, y):

dw = self.lr * (y_i - self.predict(x_i))

self.w_[1:] += dw * x_i

# bias update; recall x_0 = 1

self.w_[0] += dw

errors += int(dw != 0.0)

self.losses_.append(errors)

return self

def _forward(self, X):

return np.dot(X, self.w_[1:]) + self.w_[0]

def predict(self, X):

return np.where(self._forward(X) >= 0., 1, 0)

Let’s train this on the above linearly separable dataset and see the results!

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn import datasets

import numpy as np

# Load the Iris dataset

iris = datasets.load_iris()

data = iris.data

target = iris.target

# Select only the Setosa and Versicolor classes (classes 0 and 1)

setosa_versicolor_mask = (target == 0) | (target == 1)

data = data[setosa_versicolor_mask]

target = target[setosa_versicolor_mask]

# Extract the sepal length and sepal width features into a dataset

sepal_length = data[:, 0]

petal_length = data[:, 2]

X = np.vstack([sepal_length, petal_length]).T

# Train the Perceptron

p = Perceptron()

p.train(X, target)

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

# Create a scatter plot of values

ax1.scatter(sepal_length[target == 0], petal_length[target == 0], label="Setosa", marker='o')

ax1.scatter(sepal_length[target == 1], petal_length[target == 1], label="Versicolor", marker='x')

# Plot separating line

w1, w2 = p.w_[1], p.w_[2]

b = p.w_[0]

x_values = np.linspace(min(sepal_length), max(sepal_length), 100)

y_values = (-w1 * x_values - b) / w2

ax1.plot(x_values, y_values, label="Separating Line", color="k")

# Set plot labels and legend

ax1.set_xlabel("Sepal Length (cm)")

ax1.set_ylabel("Petal Length (cm)")

ax1.legend(loc='upper right')

ax1.set_title('Perceptron Output')

# Plot perceptron loss

ax2.plot(p.losses_, label="Error", color="r")

ax2.set_xlabel("Epoch")

ax2.set_ylabel("Error")

ax2.legend(loc='upper left')

ax2.set_title('Perceptron Errors')

# Show the plot

plt.show()

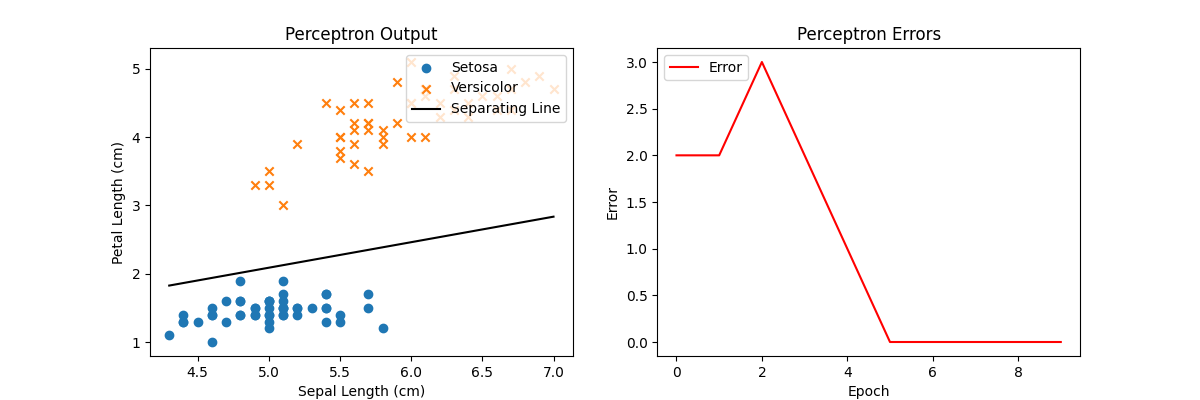

After training the perceptron on the dataset, we get a line in 2D that separates the two classes. In the general case, for a dataset where the inputs are $d$-dimension, we’d get a $(d-1)$-dimensional hyperplane. The right plot shows the number of errors the perceptron model occurs as we train on the dataset; if the dataset is linear, the perceptron is guaranteed to converge to some solution after a finite number of tries.

Since our dataset was linearly separable, we were able to converge to a solution in just a few iterations! Note that the result is complete, but maybe not optimal. Feel free to experiment with different kinds of weight initialization and learning rates!

Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs)

Even with the improvements on the perceptron from the simpler artificial neuron model, we still can’t solve the XOR problem since perceptrons only work for linearly separable data. But recall back to when we were talking about biological neurons. After consuming input from the dendrites, if we’ve accumulated enough inputs to fire the neuron, it’ll fire along the output axon which in turn is used as the input to other neurons. So it seems, at least biologically, that neurons feed into other neurons.

We can also feed our artificial neurons into other neurons and create connections between them. There are a number of different choices for how we connect them; we could even connect neurons recurrently to themselves! But the simplest thing to try is to connect the outputs of the two inputs to another neuron before producing the output.

A multilayer perceptron (MLP) takes the output of one perceptron and feeds it into another perceptron. The edges represent the weights and the circles represent the biases. Here is a 2-layer perceptron with a hidden layer of 2 neurons and output layer of 1 neuron.

This structure is called a multilayer perceptron (MLP) and the intermediate layer is called a hidden layer since it maps an observable input to an observable output, but the hidden layer itself might not directly have an observable result or interpretation. In this particular example, we have 9 learnable parameters $w_1$, $w_2$, $w_3$, $w_4$, $b_1$, $b_2$, $w_5$, $w_6$, and $b_3$. Solving for these parameters via inspection is still possible by making one key observation: we can redefine an XOR gate as a combination of other gates: $a \tt{~XOR~} b = (a\tt{~OR~}b) \tt{~AND~} (a\tt{~NAND~}b)$. We’ve already seen the AND and OR gates so we need to figure out the right weights and bias for the NAND gate. Test this yourself, but the one set of values that satisfies the NAND gate is $w_1=-1$, $w_2=-1$, $b=1$. Because of this decomposition of the XOR gate, we can try to recreate it using those same weights and values.

One way to interpret this solution to the XOR gate problem is that the top hidden neuron represents $h_1 = x_1\tt{~OR~}x_2$ and the bottom one represents $h_2 = x_1\tt{~NAND~}x_2$. Then the final one represents $h_1\tt{~AND~}h_2 = (x_1\tt{~OR~}x_2) \tt{~AND~} (x_1\tt{~NAND~}x_2)=x_1 \tt{~XOR~} x_2$. Now we have a solution to classify even nonlinear data!

In theory this seems to work, but let’s try to plug in some values and run it though this MLP to see if it produces the right outputs. We’ll call the hidden layer outputs $h_1=f(x_1+x_2-1)$ and $h_2=f(-x_1-x_2+1)$. The final output is then $y=f(h_1+h_2-2)$. Here’s a truth table showing the inputs and outputs.

| $x_1$ | $x_2$ | $h_1$ | $h_2$ | $y$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $0$ | $0$ | $1$ | $0$ |

| $0$ | $1$ | $1$ | $1$ | $1$ |

| $1$ | $0$ | $1$ | $1$ | $1$ |

| $1$ | $1$ | $1$ | $0$ | $0$ |

Seems like this MLP works to correctly produce the right outputs for the XOR gate! This is pretty interesting because a single perceptron couldn’t solve the XOR gate problem because the XOR gate wasn’t linearly separable. But it seems by layering perceptrons, we can correctly classify even nonlinear output! To understand why, let’s try plotting the values of the hidden layer using the truth table above.

We can plot the hidden state values in the 2D plane in the same way as plotting the logic gates. Notice that in the latent space, the XOR gate is indeed linearly separable so we only need one additional perceptron on this hidden state to complete our MLP representation of the XOR gate!

This is particularly insightful: in the input space, the XOR gate is not linearly separable but in the hidden/latent space it is! This is a general observation about neural networks: they perform a series of transforms until the final data are linearly separable, then we just need a single perceptron to separate them. Layering perceptrons provides more expressive power to the MLP to separate nonlinear datasets by passing them through multiple transforms. Even this MLP model has limitations as we scale up to many hundreds, thousands, millions, and billions of parameters! We’ll still need to come up with a way to automatically learn the parameters of these kinds of very large neural networks but we’ll save that for next time!

Conclusion

Neural networks have gained immense traction in the past decade for their exceptional performance across a wide variety of different tasks. Historically, these arose from trying to model biological neurons in an effort to create artificial intelligence. From these simple biological models, we derived a few parametrized mathematical models of these. We moved on to perceptrons as a start and learned what their parameters were and how to train them using the Perceptron Learning Algorithm. We showed how they can successfully classify real-world, linearly-separable data. However we found limitations in them, particularly with nonlinear datasets, even the simplest cases such as recreating an XOR gate. But we found that by layering these together into multilayer perceptrons (MLPs), we could even separate some nonlinear datasets!

We solved for the parameters of the MLP by inspection but this isn’t possible for very large neural networks so we’ll need an algorithm to automatically learn these parameters given the dataset. Furthermore, there have been a number of advancements in neural networks to improve their efficiency and robustness, and we’ll discuss the training algorithm and some of these advancements in the next post 🙂