Neural Nets - Part 3: Artificial Neural Networks and Backpropagation

In the previous post, we extended our perceptron model to a more modern artificial neuron model and learned how to train it using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) on the Iris dataset. However, we only did this for a single neuron. Practically, we’ve already shown that we can compose perceptrons together into multilayer perceptrons for much more expressive power so can we do the same thing with our new modern artificial neurons and train them using SGD?

In this post, we’ll compose our modern artificial neurons together into an actual artificial neural network (ANN) and discuss how to train an ANN using the most important and fundamental algorithm in all of deep learning: backpropagation of errors. In fact, we’re going to derive this algorithm for ANNs of any width, depth, and activation and cost function! Similar to previous posts, we’ll implement a generic ANN and the backpropagation algorithm in Python code using numpy. However, this time we’ll use a more complex dataset to highlight the expressive power of a full ANN.

Disclaimer: this part is going to have a lot of maths and equations since I want to properly motivate backpropagation and dispel any myths and misconceptions about backpropagation being this magical thing known only to machine learning library implementers and to combat those saying “ah just let X library take care of it; it’ll ‘just work’”. To make this understanding more accessible, I’ll have sections that summarize the high-level ideas as well as intuitive explanations for each of the core equations.

Neural Network Architecture

A two-layer network is composed by taking the output of the previous layer’s neurons and feeding them as input to each of the next layer’s neurons to create an all-to-all connection across layers. We don’t currently consider self-connections although there are network architectures, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs), that do.

From the previous post in the series, we’re already familiar with building a perceptron network that has an intermediate hidden layer to solve the XOR gate problem. We saw that adding this hidden layer gave our model far more expressive power than a single layer. This structure or architecture, however, is general enough we can call it an artificial neural network: we have an input layer, any number of hidden layers, and an output layer. Layer to layer, we connect each neuron of the previous layer to each neuron of the next layer, forming a many-to-many connection.

Zooming into a single neuron, we take the weighted sum of its inputs and add a bias to form the pre-activation. One way to represent a bias is a “weight” whose input is always $+1$. The weights and bias are learning parameters of the network through some learning algorithm such as gradient descent. The activation function is applied to the pre-activation to produce the neuron output. This output is fed into each of the next layer’s neurons.

To compute a value for each neuron, we take the weighted sum of its inputs plus the bias to compute a pre-activation, and then run the pre-activation through an activation function to get the actual activation/value of the neuron. Then that activation becomes an input into the next layers neurons. Finally, we have an output layer that computes some value that’s useful for evaluation, e.g., a number for linear regression or a class label.

The intuition behind having multiple hidden layers is that it gives the network more expressive power. We saw this with the XOR gate problem: the input space wasn’t linear separable but the hidden space was. One interpretation of these hidden layers is that they transform the input space nonlinearly until the output space is linear separable. A complementary interpretation is that the hidden layers iteratively build complexity from the earlier layers to the later layers. It’s easier to see this with neural networks that operate on images, i.e., convolutional neural networks: the weights of the earlier layers activate on simple lines and edges while the weights of the later layers compose these to activate on shapes and more complex geometry.

Let’s introduce/re-introduce some notation to make talking about pre-activations, activations, weights, biases, layers, and other neural network stuff easier. I’m a fan of Michael Nielsen’s notation since I think it makes the subsequent analysis easier to understand and pattern-match against so we’ll use that going forward.

Let’s consider neural networks with $L$ total layers, indexed by $l\in [1, L]$. We define a bias vector vector $b^l$ with components $b_j^l$ for each layer $l$. The superscripts here mean layer not exponents! Between layers, we collect all of the individual weights into a weight matrix $W^l$ with elements $W_{jk}^l$ that represent the value of the individual weight from neuron $k$ in layer $(l-1)$ to neuron $j$ in layer $l$, i.e., $W_{jk}^l$ is the weight from neuron $k\to j$ from layer $(l-1)$ to $l$. Notice the first index represents the neuron in layer $l$ and the second is the neuron in layer $l-1$; Michael Nielsen defines the weight matrix this way since it simplifies some of the equations and makes the intuition easier to understand.

An entry in the weight matrix $W_{jk}^l$ is the value connecting the $k$-th neuron in the $(l-1)$-th layer with the $j$-th neuron in the $l$-th layer. When we compute the input for any particular neuron, we sum over all of the output activations of the previous layer, hence the $\sum_k W_{jk}^l a_k^l$ part of the pre-activation.

For the input layer, we can define the pre-activation as the weighted sum of the inputs and weights plus the bias $z_j^1=\sum_k W_{jk}^1 x_k + b_j^1$; we can write it in a vectorized form like $z^1= W^1 x + b^1$. The activation just runs the pre-activation through an activation function $\sigma(\cdot)$ like $a_j^1=\sigma(z_j^1)$ or $a^1=\sigma(z^1)$ for the vectorized version (assuming the activation function is applied element-wise). For the next layer, we use the activations of the previous layer all the way until we get to the activations for the last layer $a^L$, also called the output layer. For simplicity, we can define the zeroth set of activations as the input $a^0 = x$ so we can write the entire set of equations in a general form for each layer.

\[\begin{align*} z_j^l &= \displaystyle\sum_k W_{jk}^l a_k^{l-1} + b_j^l & z^l &= W^l a^{l-1} + b^l\\ a_j^l &= \sigma(z_j^l) & a^l &= \sigma(z^l)\\ \end{align*}\]Performing a forward pass/inference is just computing $z^l$ and $a^l$ all the way to the final output layer $L$. During training, that final output $a^L$ goes into the cost function to determine how well the current set of weights and biases help produce the desired output. For tasks like classification, we can express the cost function in terms of the output layer activations $a^L$ and the desired class $y$ like $C(a^L, y)$. Note that if we were to “unroll” $a^L$ and all activations back to the input, $a^L$ would expand into a huge equation that would be a function of all of the weights and biases in the network so putting in the cost function is really evaluating all of the weights and biases.

This is a lot of notation but take a second to understand the placement of indices and what they represent. As an example, suppose we wanted to compute $z_1^l$, then substituting $j=1$ into the pre-activation equation, we get $\sum_k W_{1k}^l a_k^{l-1} + b_1^l$. Intuitively, this means we take each $k$ neurons from the $(l-1)$ th layer as a vector, multiply by the 1st column of the weight matrix, and add the 1st component of the bias vector to get the 1st vector component of the pre-activation. Make sure the indices match up and make sense, i.e., there should be the same number of free lower indices on both sides of any equation! Try other kinds of substitutions to make sure you understand how the index placement works.

Backpropagation of Errors

In the previous post, we demonstrated how to train a single neuron using gradient descent by computing the partial derivatives of the cost function with respect to the weights and bias. That is actually still the exact same principle and idea that we’ll be going forward with; it’s just that in the general case, the maths gets a bit more complicated since we have multiple sets of parameters across multiple layers written as functions of each other. Rather than computing individual partial derivatives for each weight and bias, we can come up with a general set of equations that tell us how to do so for any width and depth of neural network.

Instead of jumping right into the maths, let’s go through a numerical example of backpropagation to get our feet wet first. I actually wrote a post many years ago on this that I’ll steal from and take this opportunity to update the writing and narrative. Since we already somewhat used backpropagation in the previous post, let’s analyze that in a bit more detail.

Computation Graphs

One useful visual representation for a a computation is a computation graph. Each node in the graph represents an operation and each edge represents a value that is the output of the previous operation. Let’s draw a computation graph for our little artificial neuron from the previous post and substitute some random values for the weights and bias.

This computation graph represents a single neuron with two inputs and corresponding weights and a bias term. Example values have been substituted and a forward pass has been computed. The $y$ value is the target/true value fed into the cost function.

In this very simple example, we have a few operations: multiplication, addition, sigmoid activation, and cost function evaluation. We’ve done a forward pass and recorded the outputs of the operands on the top of the line. At the very last step, we have a sigmoid output of 0.73 but a desired output of 1. So the goal is to adjust our weights and biases such that, the next time we perform a forward pass, the output of the model is closer to 1. What we did last time was to compute the partial derivatives of the cost function with respect to each parameter by expanding out the entire cost function and analytically computing derivatives. One of the things we saw was that all of the learnable parameters had similar terms in their derivatives, namely $\frac{\p C}{\p a}$ and $\frac{\p C}{\p z}$. Was this coincidental or a byproduct of how we compute the output of a neuron?

To answer this question, we’re going to take a slightly different, but equivalent, approach at computing the partial derivatives by using the graph as a visual guide for which derivatives compose. For each node, we’re going to take the derivative of the operation with respect to each of the inputs and accumulate the overall gradient, starting at the end, through the graph until we get all the way back to the parameters of the model at the very left of the graph. We’ll start with the first derivative $\frac{\p C}{\p a}$ and keep tacking on factors as we go backwards through the graph. For example, the next factor we’ll tack on is $\frac{\p a}{\p z}$ to get $\frac{\p C}{\p a}\frac{\p a}{\p z}=\frac{\p C}{\p z}$. By multiplying through the partial derivatives this way, propagating the gradient signal backwards through the graph is equivalent to applying the chain rule. By the time we get to the model parameters, we will have computed something like $\frac{\p C}{\p w_1}$ and we can simply read this off the graph.

Let’s start with the output layer and the cost function. We’re using the quadratic cost function that looks like this for a single output: $C(a, y) = \frac{1}{2}(y - a)^2$. There are technically two possible partial derivatives of this function $\frac{\p C}{\p a}$ and $\frac{\p C}{\p y}$ but the latter doesn’t make sense since $y$ is given and not a function of the parameters of the model so let’s compute the former. We’ve already done so in the previous post so we’ll lift the derivative from there.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\p C}{\p a} &= -(y-a)\\ &= -(1 - 0.73)\\ &= -0.27 \end{align*}\]Computing the derivative and substituting our values, we get $-0.27$ for the start of the gradient signal.

We’ve computed the gradient of the cost function with respect to its inputs and placed it below the corresponding edge in green. Since $y$ is given, we don’t compute a gradient to it.

We’re going to write the gradient values under the edges and track them as we move backward through the graph. Now the next operation we encounter is the sigmoid activation function $\sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1+e^{-z}}$. Let’s compute the derivative of the sigmoid with respect to input $z$. Similar to the above example, we already know a closed-form of $\sigma’(z)$ from the previous post so we’ll lift the derivative from there.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\p a}{\p z} &= \sigma(z)\big[1-\sigma(z)\big]\\ &= a(1-a)\\ &= 0.73(1-0.73)\\ &= 0.1971 \end{align*}\]Computing the derivative and substituting values, we get $0.1971$. Now do we add this number underneath the corresponding edge of the graph? Not quite. We could call this value a local gradient since we’re just computing the gradient of a single node with respect to its inputs. But remember what we said above: propagating the gradient is equivalent to applying the chain rule so we actually need to multiply this by $-0.27$ to get the total gradient $\frac{\p C}{\p a}\frac{\p a}{\p z}=\frac{\p C}{\p z}=-0.27(0.1971)=-0.053$ which we can put underneath the corresponding edge.

We’ve computed the gradient of the activation function with respect to its inputs. To get the actual gradient, we multiply it with the previous gradient from the cost function so that we have a full global gradient.

Now we’ve reach our first parameter the bias $b$! Same as before, we’ll compute the local gradient and multiply by the thus-far accumulated gradient. To make things a bit easier, let’s just define $\Omega \equiv w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2$ so the operation can be defined like $z = \Omega + b$. We have two local gradients to compute $\frac{\p z}{\p \Omega}$ and $\frac{\p z}{\p b}$. Fortunately, this is easy since the derivative of a sum with respect to either terms is 1 so $\frac{\p z}{\p \Omega}=\frac{\p z}{\p b}=1$ so we just “copy” the gradient along both input paths of the addition node. We’ve successfully computed the gradient of the cost function with respect to our bias parameter!

We’ve computed the gradient across the weighted sum and bias. Notice that the gradient is “copied” across addition nodes because the derivative of a sum with respect to the terms is always $+1$.

We have two more parameters to go. The next node we encounter on our way to the weights is another addition node. Similar to what we just did, we can “copy” the gradient along both paths.

Let’s first consider $w_1$ and now we encounter a multiplication node. Similarly, we can define $\omega_1 = w_1 x_1$ and compute just the local gradient $\frac{\p \omega_1}{\p w_1}$ since $\frac{\p \omega_1}{\p x_1}$ is fixed just like with the output.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\p \omega_1}{\p w_1} &= x_1\\ &= -1\\ \end{align*}\]Multiplying this with the incoming gradient we get the total gradient of $\frac{\p C}{\p a}\frac{\p a}{\p z}\frac{\p z}{\p\Omega}\frac{\p \Omega}{\p \omega_1}\frac{\p \omega_1}{\p w_1} = \frac{\p C}{\p w_1} = 0.053$. Collapsing the identity terms, a more meaningful application of the chain rule would be $\frac{\p C}{\p a}\frac{\p a}{\p z}\frac{\p z}{\p w_1} = \frac{\p C}{\p w_1} = 0.053$. We can easily figure out the other derivative $\frac{\p C}{\p a}\frac{\p a}{\p z}\frac{\p z}{\p w_2} = \frac{\p C}{\p w_2} = -0.053(-2)=0.106$ by noting that for a multiplication node, the local gradient of one of the inputs is the other input so $\frac{\p z}{\p w_2}=x_2$.

We’ve computed all of the gradients in the computation graph, including the weights. For a multiplication gate, the gradient of a particular term is the product of the other terms. For example, $\frac{\p}{\p a}abc=bc$ and the other derivatives follow. For a product like this, we multiply by the incoming gradient.

Now we’ve computed the gradient of the cost function for every parameter so we’re ready for a gradient descent update!

\[\begin{align*} w_1&\gets w_1 - \eta\frac{\p C}{\p w_1}\\ w_2&\gets w_2 - \eta\frac{\p C}{\p w_2}\\ b&\gets b - \eta\frac{\p C}{\p b} \end{align*}\]Let’s set the learning rate to $\eta=1$ for simplicity and perform a single update to get new values for our parameters.

\[\begin{align*} w_1 &\gets 2 - (0.053) &= 1.94\\ w_2 &\gets -3 - (0.106) &= -3.106\\ b &\gets -3 - (-0.053) &= -2.947 \end{align*}\]If we run another forward pass with these new parameters, we get $a=0.79$ which is closer to our target value of $y=1$! We’ve successfully performed gradient descent numerically by hand and saw that it does, in fact, adjust the model parameters to get us closer to the desired output!

To summarize, a computation graph is a useful tool for visualizing a larger computation in terms of its constituent operations, represented as nodes in the graph. To perform backpropagation on this graph, we start with the final output and work our ways backwards to each parameter, accumulating the global gradient as we go by successively multiplying it by the local gradient at each node. The local gradient at each node is just the derivative of the node with respect to its inputs. If we keep doing this, we’ll eventually arrive at the global gradient for each parameter which is equivalent to the derivative of the cost function with respect to the parameter. We can directly use this gradient in a gradient descent update to get our model closer to the target value.

Backpropagation Equations

Now that we’ve seen backpropagation work in a few different cases, e.g., single neuron and computation graph, we’re ready to actually derive the general backpropagation equations for any ANN. This is where the maths is going to start getting a little heavy so feel free to skip to the last paragraph of this section. I’ll be loosely following Michael Nielsen’s general approach here since I like the high-level way he’s structured the derivation. We’re going to start with computing the gradient of the cost function with respect to the output of the model, then come up with an equation for propagating a convenient intermediate quantity (he calls this the “error”) from layer to layer, and finally two more equations to compute the partial derivatives of the weights and bias of a particular layer with respect to that intermediate quantity of the layer.

From the previous section, we started with computing the gradient of the cost function with respect to the entire model output first so that sounds like a sensible thing to compute first: $\frac{\p C}{\p a_j^L}$ or $\nabla_{a^L}C$ in vector form. We’re making an implicit assumption that the cost function is a function of the output of the network but that’s most often the case. There are more complex models that account for other things in the cost function, but it’s a reasonable assumption to make. Note that this gradient is entirely dependent on the cost function we use, e.g. mean absolute error, mean squared error, or something more interesting like Huber loss, so we’ll leave it written symbolically.

Going a step further, we want to compute the derivative of the cost function with respect to the weights and biases of the very last layer, i.e., $\frac{\p C}{\p W_{jk}^L}$ and $\frac{\p C}{\p b_j^L}$. To do this, we’ll have to go backwards through the activation function first $\frac{\p C}{\p a_j^L}\frac{\p a_j^L}{\p z_j^L}=\frac{\p C}{\p z_j^L}$. One thing to note is that, for every layer, the pre-activation is always a function of the weights and biases at the same layer. By that logic, if we could compute $\frac{\p C}{\p z_j^l}$ for each layer, the gradients of the weights and biases would just be another factor tacked on to this. For convenience purposes, it seems like a good idea to define a variable and name for this quantity so let’s directly call this the error in neuron $j$ in layer $l$.

\[\begin{equation} \delta_j^l \equiv \frac{\p C}{\p z_j^l} \end{equation}\]Note that we could have defined the error in terms of the activation rather than the pre-activation like $\frac{\p C}{\p a_j^l}$ but then there would be an extra step to go through the activation into the pre-activation anyways (for each weight matrix and bias vector) so it’s a bit simpler to define it in terms of the pre-activation. But everything we do past this point could be done using $\frac{\p C}{\p a_j^l}$ as the definition of the error without loss of generality.

A visual way to think about the error is taking the green gradient path from the cost function to the pre-activation $z_j^l$ (across its activation $a_j^l$) of a particular neuron.

Intuitively, $\delta_j^l$ represents how a change in the pre-activation in a neuron $j$ in a layer $l$ affects the entire cost function. This little wiggle in the pre-activation occurs from a change in the weights or bias but since the pre-activation is a function of both, we use it to represent both kinds of wiggles. It’s really just a helpful intermediate quantity that simplifies some of the work of propagating the gradient backwards.

Now that we have this quantity, the first step is to compute this error at the output layer $L$. Let’s substituting $l=L$ into the definition of $\delta_j^l$

\[\begin{align*} \delta_j^L &= \frac{\p C}{\p z_j^L}\\ &= \sum_k\frac{\p C}{\p a_k^L}\frac{\p a_k^L}{\p z_j^L}\\ &= \frac{\p C}{\p a_j^L}\frac{\p a_j^L}{\p z_j^L}\\ &= \frac{\p C}{\p a_j^L}\sigma'(z_j^L) \end{align*}\]Between the first and second steps, we have to sum over the activations of all of the output layer since the cost function depends on all of them. Between the second and third steps, we used the fact that the pre-activation $z_j^L$ is only used in the corresponding activation $a_j^L$ and any other $a_k^L$ is not a function of $z_j^L$. So the only activation that is a function of $z_j^L$ is $a_j^L$. So all of the other terms in the sum disappear. So now we have an equation telling us the error in the last layer.

\[\begin{equation} \delta_j^L = \frac{\p C}{\p a_j^L}\sigma'(z_j^L) \end{equation}\]and its vectorized counterpart

\[\begin{equation} \delta^L = \nabla_{a^L}C \odot \sigma'(z^L) \end{equation}\]where $\odot$ is the Hadamard product or element-wise multiplication. Intuitively, this equation follows from the derivation: to get to the pre-activation at the last layer, we have to move the gradient backwards through the cost function and then again backwards through the activation of the last layer.

For the first backpropagation equation, we apply the definition of the error, but move back only to the output layer. To get to the pre-activation $z_j^L$, we start at the cost function $\frac{\p C}{\p a_j^L}$ and through the corresponding activation $\frac{\p a_j^L}{\p z_j^L}$ to get the total gradient $\frac{\p C}{\p a_j^L}\frac{\p a_j^L}{\p z_j^L}=\frac{\p C}{\p a_j^L}\sigma’(z_j^L)=\delta_j^L$.

Now we could go right into computing the weights and biases from here, but let’s first figure out a way to propagate this error from layer to layer first and then come up with a way to compute the derivative of the cost function with respect to the weights and biases of any layer, including the last one. So we’re looking to propagate the the error $\delta^{l+1}$ from a particular layer $(l+1)$ to a previous layer $l$. Specifically, we want to write the error in the previous layer $\delta^l$ in terms of the error of the next layer $\delta^{l+1}$. As we did before, we can start with the definition of $\delta^l$ and judiciously apply the chain rule.

\[\begin{align*} \delta_k^l &= \frac{\p C}{\p z_k^l}\\ &= \sum_j \frac{\p C}{\p z_j^{l+1}}\frac{\p z_j^{l+1}}{\p z_k^l}\\ &= \sum_j \delta_j^{l+1}\frac{\p z_j^{l+1}}{\p z_k^l} \end{align*}\]Between the second and third steps, we substituted back the definition of $\delta_j^{l+1}=\frac{\p C}{\p z_j^{l+1}}$ just using $k\to j$ and $l\to (l+1)$ from the original definition (both are free indices). Now we have $\delta^l$ in terms of $\delta^{l+1}$! The last remaining thing to expand is $\frac{\p z_j^{l+1}}{\p z_k^l}$.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\p z_j^{l+1}}{\p z_k^l} &= \frac{\p}{\p z_k^l}z_j^{l+1}\\ &= \frac{\p}{\p z_k^l}\bigg[\sum_p W_{jp}^{l+1}a_p^l + b_j^{l+1}\bigg]\\ &= \frac{\p}{\p z_k^l}\bigg[\sum_p W_{jp}^{l+1}\sigma(z_p^l) + b_j^{l+1}\bigg]\\ &= \frac{\p}{\p z_k^l}\sum_p W_{jp}^{l+1}\sigma(z_p^l)\\ &= \frac{\p}{\p z_k^l} W_{jk}^{l+1}\sigma(z_k^l)\\ &= W_{jk}^{l+1}\frac{\p}{\p z_k^l} \sigma(z_k^l)\\ &= W_{jk}^{l+1}\sigma'(z_k^l)\\ \end{align*}\]This derivation is more involved. In the second line, we expand out $z_j^{l+1}$ using its definition; note that we use $q$ as the dummy index to avoid any confusion. In the fourth line, we cancel $b_j^{l+1}$ since it’s not a function of $z_k^l$. Going to the fifth line, similar to the reasoning earlier, the only term in the sum that is a function of $z_k^l$ is when $p=k$ so we cancel all of the other terms. Then we differentiate as usual. We can take this result and plug it back into the original equation.

\[\begin{equation} \delta_k^l = \sum_j W_{jk}^{l+1}\delta_j^{l+1}\sigma'(z_k^l) \end{equation}\]To get the vectorized form, note that we have to transpose the weight matrix since we’re summing over the rows instead of the columns; also note that the last term is not a function of $k$ so we can take the Hadamard product.

\[\begin{equation} \delta^l = (W^{l+1})^{T}\delta^{l+1}\odot\sigma'(z^l) \end{equation}\]This is why we intentionally ordered the terms in the multiplication this way: to better show how it translates into matrix product and why we use the transpose of weight matrix.

For the second backpropagation equation, we assume we’ve already computed the error at some layer $(l + 1)$ and try to propagate it back to layer $l$. We can always apply this to the last and second-to-last layer anyways. Starting from $\delta_j^{l+1}$, to get to $\delta_k^l$, we need to move backwards through the weight matrix and through the activation. In the forward pass, since we compute the pre-activation of a neuron using the weighted sum of all previous activation, to compute gradient, we need the sum of all of the previous errors, weighted by the transpose of the weight matrix (consider the dimensions) which explains the $\sum_j W_{jk}^{l+1}\delta_j^{l+1}$ part. Then we move backwards through the cost function which explains the $\sigma’(z_k^l)$ term.

This has an incredibly intuitive explanation: since the weight matrix propagates inputs forward, the transpose of the weight matrix propagates errors backwards, specifically the error in the next layer $\delta^{l+1}$ to the current layer. Another way to think about it is in terms of the dimensions of the matrix: the weight matrix multiples against the number of neurons of the previous layer to produce the number of neurons in the next layer so the transpose of the weight matrix multiples against the number of neurons in the next layer and produces the number of neurons in the previous layer. After the weight matrix multiplication, we have to Hadamard with the derivative of the activation function to move the error backward through the activation to the pre-activation.

We’re almost done! The last two things we need are the actual derivatives of the cost function with respect to the the weights and biases. Fortunately, they can be easily expressed in terms of the error $\delta_j^l$. Let’s start with the bias since its easier. This time, we can start with what we’re aiming for and then decompose in terms of the error.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\p C}{\p b_j^l} &= \sum_k\frac{\p C}{\p z_k^l}\frac{\p z_k^l}{\p b_j^l}\\ &= \frac{\p C}{\p z_j^l}\frac{\p z_j^l}{\p b_j^l}\\ &= \delta_j^l\frac{\p z_j^l}{\p b_j^l}\\ &= \delta_j^l\frac{\p}{\p b_j^l}\Big(\sum_k W_{jk}^l a_k^{l-1} + b_j^l\Big)\\ &= \delta_j^l \end{align*}\]In the first step, we use the chain rule to expand the left-hand side. Similar to the previous derivations, all except for one term in the sum cancels. Then we plug in the definition of the error and differentiate.

\[\begin{equation} \frac{\p C}{\p b_j^l} = \delta_j^l \end{equation}\]The vectorized version looks almost identical!

\[\begin{equation} \nabla_{b^l}C = \delta^l \end{equation}\]Note that if we had defined the error as the gradient of the cost function with respect to the activation, we’d have to take an extra term moving it across the pre-activation.

Remember that one way to interpret the bias is being a “weight” whose input is always $+1$. Similar to the second backpropagation equation, we’ll assume we’ve computed $\delta_j^l$. To get to the bias $b_j^l$, we don’t have to do anything extra since the input term is simply $+1$.

Turns out the derivative of the cost function with respect to the bias is exactly equal to the error! Convenient that it worked out this way!

Now we just need the corresponding derivative for the weights. It’ll follow almost the same pattern.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\p C}{\p W_{jk}^l} &= \sum_q\frac{\p C}{\p z_q^l}\frac{\p z_q^l}{\p W_{jk}^l}\\ &= \frac{\p C}{\p z_j^l}\frac{\p z_j^l}{\p W_{jk}^l}\\ &= \delta_j^l\frac{\p z_j^l}{\p W_{jk}^l}\\ &= \delta_j^l\frac{\p}{\p W_{jk}^l}\Big(\sum_p W_{jp}^l a_p^{l-1} + b_j^l\Big)\\ &= \delta_j^l\frac{\p}{\p W_{jk}^l}W_{jk}^l a_k^{l-1}\\ &= \delta_j^l a_k^{l-1} \end{align*}\]Be careful with the indices! The first step we use a dummy index $q$ to not confuse indices. The only term in the sum that is nonzero is $z_j^l$; remember that the second in index in the weight matrix is summed over so only the first one allows us to cancel the other terms. Then we can expand out using a dummy index again and apply the same reasoning to cancel out other terms in the sum. Then we differentiate.

\[\begin{equation} \frac{\p C}{\p W_{jk}^l} = \delta_j^l a_k^{l-1} \end{equation}\]Note that all indices are balanced on both sides of the equation so we haven’t made any obvious mistake in the calculation.

Like the previous two backpropagation equations, we’ll assume we’ve computed $\delta_j^l$. To get to the weight between two arbitrary neurons $W_{jk}^l$, the two terms involved are the error $\delta_j^l$ which is the error at the $j$th neuron and the activation of the $k$th neuron that it connects to.

The intuitive explanation for this is that $a_k^{l-1}$ is the “input” to a neuron through a weight and $\delta_j^l$ is the “output” error; this says the change in cost function as a result of the change in the weight is the product of the activation going “into” the weight times the resulting error “output”. The vectorized version uses the outer product since, for a matrix $M_{ij}=x_i y_j \leftrightarrow M=xy^T$.

\[\begin{equation} \nabla_{W^l}C = \delta^l (a^{l-1})^{T} \end{equation}\]That’s the last equation we need for a full backpropagation solution! Let’s see them all in one place here, both in element and vectorized form!

\[\begin{align*} \delta_j^l &\equiv \frac{\p C}{\p z_j^l} & \delta^l &\equiv \nabla_{z^l} C\\ \delta_j^L &= \frac{\p C}{\p a_j^L}\sigma'(z_j^L) & \delta^L &= \nabla_{a^L}C \odot \sigma'(z^L)\\ \delta_k^l &= \sum_j W_{jk}^{l+1}\delta_j^{l+1}\sigma'(z_k^l) & \delta^l &= (W^{l+1})^{T}\delta^{l+1}\odot\sigma'(z^l)\\ \frac{\p C}{\p b_j^l} &= \delta_j^l & \nabla_{b^l}C &= \delta^l\\ \frac{\p C}{\p W_{jk}^l} &= \delta_j^l a_k^{l-1} & \nabla_{W^l}C &= \delta^l (a^{l-1})^{T}\\ \end{align*}\]With this set of equations, we can train any artificial neural network on any set of data! Take a second to prod at what happens when various values such as what happens when $\sigma’(\cdot)\approx 0$. This should help give some insight on how quickly or efficiently training can happen, for example. There are some other insights we can gain from analyzing these equations further but that’s a bit tangential to this current discussion and best saved for when we encounter problems (“seeing is believing”).

Backpropagation Algorithm

Now we can describe the entire backpropagation algorithm in the context of stochastic gradient descent (SGD).

- Initialize the weights $W^l$ and biases $b^l$ for each layer $l=1,\dots,L$

- For each epoch

- Sample a minibatch $\{x^{(i)}, y^{(i)}\}$ of size $m$

- For each example $(x^{(i)}, y^{(i)})$ in the minibatch

- Forward pass to compute each $z^l = W^l a^{l-1} + b^l$ and $a^l=\sigma(z^l)$ for $l=1,\dots,L$

- Compute the error in the last layer $\delta^L = \nabla_{a^L}C \odot \sigma’(z^L)$

- Backward pass to compute error for each layer $\delta^l = (W^{l+1})^{T}\delta^{l+1}\odot\sigma’(z^l)$

- Update all weights using $W^l\gets W^l-\eta\frac{1}{m}\sum_x\delta^l (a^{l-1})^{T}$ and all biases using $b^l\gets b^l-\eta\frac{1}{m}\sum_x\delta^l$, respectively. Average the gradient over all of the training examples in the minibatch and apply the learning rate.

This algorithm follows suit from the previous SGD training loop we wrote except now we’re computing an intermediate quantity (the error $\delta^l$), and have more complicated update equations.

Neural Network Implementation

We’ve derived the equations for backpropagation so we’re ready to implement and train a general artificial neural network in Python! But before we dive into the code, our dataset is going to be different than the Iris dataset. I want to highlight how general ANNs can solve more complex problems than singular neurons so the dataset is going to be more complicated.

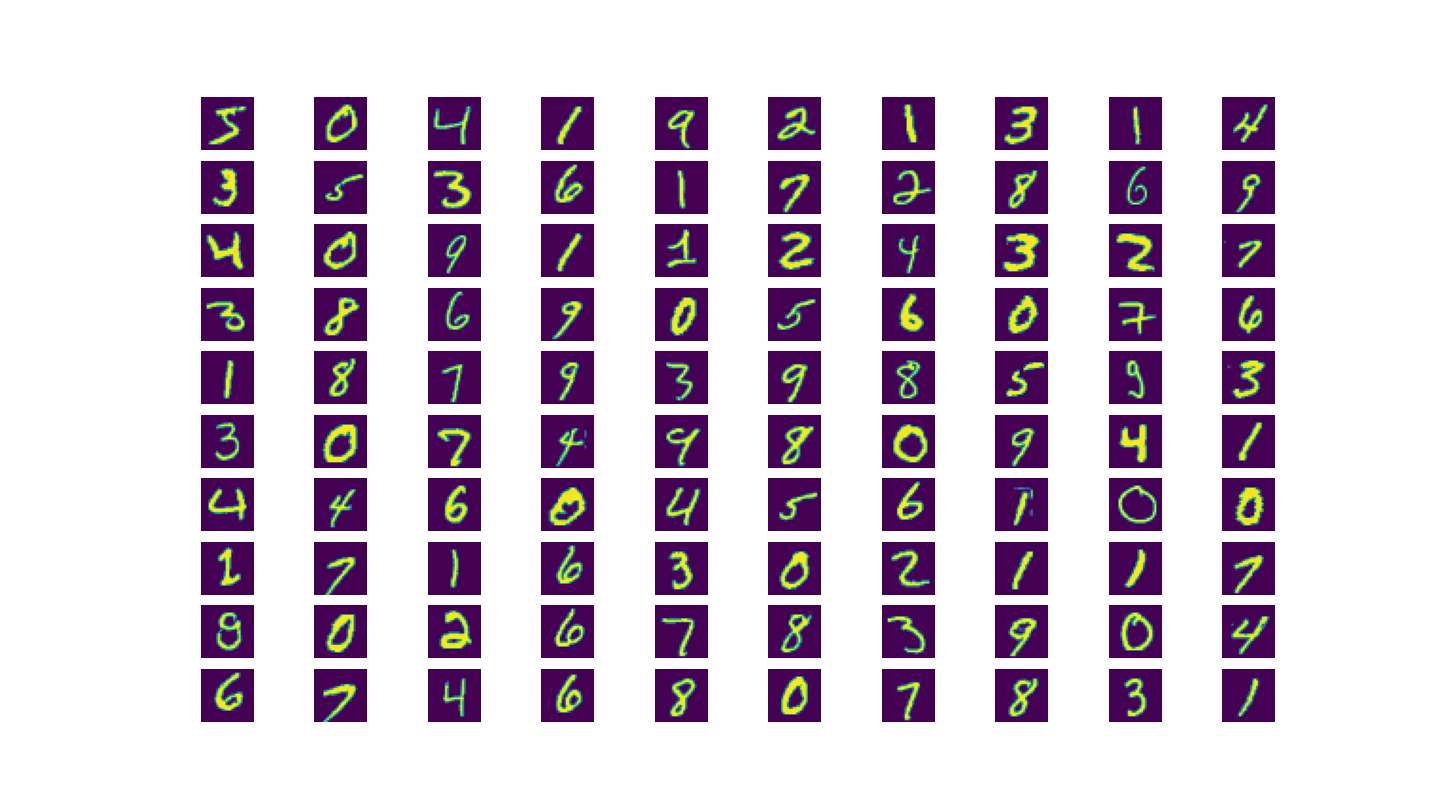

We’ll be training on a famous data called the MNIST Handwritten Digits dataset. As the name implies, it’s a dataset of handwritten digits 0-9 represented as grayscale images. Each image is $28\times 28$ pixels and the true label is a digit 0-9. It’s always a good idea to look at raw data of a dataset that we’re not familiar with so that we understand what the inputs correspond to in the real world.

MNIST Handwritten Digits Dataset contains tens of thousands of handwritten digits from 0-9. We can plot some example data from the training set in a grid.

Now that we’ve seen some data, we can start writing the data pre-processing step. In practice, this data pipeline is often more important than the exact model or network architecture. Running poorly-processed data through even the state-of-the-art model will produce poor results. To start, we’re going to use the Pytorch machine learning Python framework to load the training and testing data. For a particular grayscale image pixel, there are a lot of data representations, but the most common are (i) an integer value in $[0, 255]$ or (ii) a floating-point value in $[0, 1]$. We’re going to use the latter since it plays more nicely, numerically, with the floating-point parameters of our model (and the sigmoid activation).

import numpy as np

from torchvision import datasets

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

# load MNIST dataset

train_dataset = datasets.MNIST('./data', train=True, download=True)

test_dataset = datasets.MNIST('./data', train=False, download=True)

X_train = train_dataset.data.numpy()

X_test = test_dataset.data.numpy()

# normalize training data to [0, 1]

X_train, X_test = X_train / 255., X_test / 255.

We can print the “shape” of this data with X_train.shape. The first dimension represents the number of examples (either training or test) and the remaining dimensions represent the data. In this case, for the MNIST training set, we have 60,000 examples and the images are all $28\times 28$ pixels so the shape of our training data is a multidimensional array of shape $(60000, 28, 28)$. The test set contains 10,000 examples for evaluation. But our neural network accepts a number of neurons as input, not a 2D image. An easy way to reconcile this is to flatten the image into a single layer. So we’ll take each $28\times 28$ image and flatten it into a single list of $28*28=784$ numbers. This will change the shape of the training data to $(60000, 784)$ but we’ll need to add an extra dimension to make Pytorch and the maths work out so we want the resulting shape to be $(60000, 784, 1)$ where the last dimension just means that one set of 784 numbers correspond to 1 input example.

# flatten image into 1d array

X_train, X_test = X_train.reshape(X_train.shape[0], -1), X_test.reshape(X_test.shape[0], -1)

# add extra trailing dimension for proper matrix/vector sizes

X_train, X_test = X_train[..., np.newaxis], X_test[..., np.newaxis]

print(f"Training set size: {X_train.shape}")

print(f"Testing set size: {X_test.shape}")

So that handles the input data, but what about the output data? Remember the output is a label from 0-9. We could just leave the label alone but there are problems with this numbering. For example, if we were to take an average across a set of output data, we’d end up with a value corresponding to a different output: the average of 0 and 4 is 2. This relation doesn’t really make sense and arises from the fact that our output data is ordinal: an integer between 0-9. We’d rather have each possible output “stretch” out into it’s own dimension so we can operate on a particular output or set of outputs independently without inadvertently considering all outputs. One way to do this is to literally put each output into it’s own dimension. This is called a one-hot encoding where we create an $n$-dimensional vector where $n$ represents the number of possible output classes. In our specific case, it maps a numerical output to a binary vector with a 1 in the index of the vector: so the digit 2 would be mapped to the vector $\begin{bmatrix}0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}^T$. We’ll do the same with the input data and expand the last dimension for the same reasons.

def to_onehot(y):

"""

Convert index to one-hot representation

"""

one_hot = np.zeros((y.shape[0], 10))

one_hot[np.arange(y.shape[0]), y] = 1

return one_hot

y_train, y_test = train_dataset.targets.numpy(), test_dataset.targets.numpy()

y_train, y_test = to_onehot(y_train), to_onehot(y_test)

y_train, y_test = y_train[..., np.newaxis], y_test[..., np.newaxis]

print(f"Training target size: {y_train.shape}")

print(f"Test target size: {y_test.shape}")

Now we’re ready to instantiate our neural network class with a list of neurons per layer and train it!

ann = ArtificialNeuralNetwork(layer_sizes=[784, 32, 10])

training_params = {

'num_epochs': 30,

'minibatch_size': 16,

'cost': QuadraticCost,

'learning_rate': 3.0,

}

print(f'Training params: {training_params}')

ann.train(X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test, **training_params)

There are a few parameters that haven’t been explained yet, but we’ll get to them. Even before the class definition, let’s define the activation and cost functions and their derivatives.

class Sigmoid:

@staticmethod

def forward(z):

return 1. / (1. + np.exp(-z))

@staticmethod

def backward(z):

return Sigmoid.forward(z) * (1 - Sigmoid.forward(z))

class QuadraticCost:

@staticmethod

def forward(a, y):

return 0.5 * np.linalg.norm(a - y) ** 2

@staticmethod

def backward(a, y):

return a - y

The forward pass computes the output based on the input and the backward pass computes the gradient. Note that the forward pass of the quadratic cost computes a vector norm since the inputs are 10-dimensional vectors and the cost function generally outputs a scalar. Now we can define the class and constructor. For the most part, we’ll just copy over the input parameters as well as initialize the weights and biases.

class ArtificialNeuralNetwork:

def __init__(self, layer_sizes: [int], activation_fn=Sigmoid):

self.layer_sizes = layer_sizes

self.num_layers = len(layer_sizes)

self.activation_fn = activation_fn

# use a unit normal distribution to initialize weights and biases

# performs better in practice than initializing to zeros

# note that weights are j in layer [i] to k in layer [i-1]

self.weights = [np.random.randn(j, k)

for j, k in zip(layer_sizes[1:], layer_sizes[:-1])]

# since the first layer is an input layer, we don't have biases for

self.biases = [np.random.randn(j, 1) for j in layer_sizes[1:]]

Notice that we’re initializing the weights and biases with a standard normal distribution rather than with zeros. This is to intentionally create asymmetry in the neurons so that they learn independently! The next function to implement is the training function. This follows from the previous ones we’ve written where we iterate over the number of epochs and then create minibatches and iterate over those.

def train(self, X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test, **kwargs):

num_epochs = kwargs['num_epochs']

self.minibatch_size = kwargs['minibatch_size']

self.cost = kwargs['cost']

self.learning_rate = kwargs['learning_rate']

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

# shuffle data each epoch

permute_idxes = np.random.permutation(X_train.shape[0])

X_train = X_train[permute_idxes]

y_train = y_train[permute_idxes]

epoch_cost = 0

for start in range(0, X_train.shape[0], self.minibatch_size):

minibatch_cost = 0

# partition dataset into minibatches

Xs = X_train[start:start+self.minibatch_size]

ys = y_train[start:start+self.minibatch_size]

self._zero_grad()

for x_i, y_i in zip(Xs, ys):

a = self.forward(x_i)

d_nabla_W, d_nabla_b = self._backward(y_i)

self._accumulate_grad(d_nabla_W, d_nabla_b)

minibatch_cost += self.cost.forward(a, y_i)

self._step()

minibatch_cost = minibatch_cost / self.minibatch_size

epoch_cost += minibatch_cost

test_set_num_correct = self.num_correct(X_test, y_test)

test_set_accuracy = test_set_num_correct / X_test.shape[0]

print(f"Epoch {epoch+1}: \

\tLoss: {epoch_cost:.2f} \

\ttest set acc: {test_set_accuracy*100:.2f}% \

({test_set_num_correct} / {X_test.shape[0]})")

There are a lot of functions that we haven’t defined yet. The first loop defines the outer loop for the epochs, then we create minibatches and iterate over those. At the start of each minibatch, we zero out any accumulated gradient since we’ll be performing a gradient descent update for each minibatch. In the innermost loop for each individual training example, notice that we do a forward pass and a backward pass that computes the weights and biases gradients. We accumulate these gradients over the minibatch. Then we call this self._step() function to perform one step of gradient descent optimization to update all of the model parameters. At the end of each minibatch, we compute the accuracy on the test set. (There a better way to compute incremental progress using something called a validation set.)

Going from top to bottom, the first function we encounter is self._zero_grad() that is called at the beginning of the minibatch loop since, for stochastic gradient descent, we accumulate the gradient over the minibatch and perform a single parameter update over the accumulated gradient of the minibatch. So we need this function to zero out the accumulated gradient for the next minibatch.

def _zero_grad(self):

self.nabla_W = [np.zeros(W.shape) for W in self.weights]

self.nabla_b = [np.zeros(b.shape) for b in self.biases]

We’re going to skip over the forward and backward passes to the self._accumulate_grad(d_nabla_W, d_nabla_b). This folds in the gradient for a single training example into the total accumulated gradient across the minibatch.

def _accumulate_grad(self, d_nabla_W, d_nabla_b):

self.nabla_W = [nw + dnw for nw, dnw in zip(self.nabla_W, d_nabla_W)]

self.nabla_b = [nb + dnb for nb, dnb in zip(self.nabla_b, d_nabla_b)]

The last function self._step() applies one step of gradient descent optimization and updates all of the weights and biases from the averaged accumulated gradient.

def _step(self):

self.weights = [w - (self.learning_rate / self.minibatch_size) * nw

for w, nw in zip(self.weights, self.nabla_W)]

self.biases = [b - (self.learning_rate / self.minibatch_size) * nb

for b, nb in zip(self.biases, self.nabla_b)]

Those are all functions that operate on the gradient and weights and biases and perform simpler calculations. The crux of this class lies in the forward and backward pass functions. For the forward pass, we define the first activation as the input and iterate through the layers applying the corresponding weights and biases and activation functions. For the backwards pass, we cache the values of the activations and pre-activations.

def forward(self, a):

self.activations = [a]

self.zs = []

for W, b in zip(self.weights, self.biases):

z = np.dot(W, a) + b

self.zs.append(z)

a = self.activation_fn.forward(z)

self.activations.append(a)

return a

The backward pass simply implements the backpropagation equations we derived earlier. The only consideration is that we need to apply the derivative of the cost and activation functions at the very end and then move backwards. One thing we do is exploit Python’s negative indexing so the first element is the last layer, the second element is the second-to-last layer, and so on.

def _backward(self, y):

nabla_W = [np.zeros(W.shape) for W in self.weights]

nabla_b = [np.zeros(b.shape) for b in self.biases]

z = self.zs[-1]

a_L = self.activations[-1]

delta = self.cost.backward(a_L, y) * self.activation_fn.backward(z)

a = self.activations[-1-1]

nabla_W[-1] = np.dot(delta, a.T)

nabla_b[-1] = delta

for l in range(2, self.num_layers):

z = self.zs[-l]

W = self.weights[-l+1]

delta = np.dot(W.T, delta) * self.activation_fn.backward(z)

a = self.activations[-l-1]

nabla_W[-l] = np.dot(delta, a.T)

nabla_b[-l] = delta

return nabla_W, nabla_b

Finally, we have an evaluation function that computes the number of correct examples. We run the input through the network and take the index of the largest activation of the output layer and compare it against the index of the one in the one-hot encoding of the label vectors.

def num_correct(self, X, Y):

results = [(np.argmax(self.forward(x)), np.argmax(y)) for x, y in zip(X, Y)]

return sum(int(x == y) for (x, y) in results)

And that’s it! We can run the code and train our neural network and see the output! Even with our simple neural network we can get to >95% accuracy on the test set! Try messing around with the other input parameters!

The full code listing can be found here.

Conclusion

We did a lot this article! We started off with our modern neuron model and extended it into layers to support multi-layer neural networks. We defined a bunch of notation to perform a forward pass to propagate the inputs all the way to the last layer. Then we started learning about how to automatically compute the gradient across all weights and biases using the backpropagation algorithm. We demonstrated the concept with a computation graph and then derived the necessary equation to backpropagate the gradient and we coded a neural network in Python and numpy and trained it on the MNIST handwritten dataset.

We have a functioning neural network written in Numpy now! We’re able to get pretty good accuracy on the MNIST data as well. However this dataset has been around for decades and is that really the best we can do? This is a good start but we’re going to learn how to make our neural networks even better with some modern training techniques 🙂