Reinforcement Learning

In the past few years, computers have achieved better than human-level performance in many different tasks such as classifying images or transcribing text from an audio recording. In addition to these kinds of tasks, computers have also beaten us humans at games: Deep Blue at chess, AlphaGo at Go, OpenAI Five at DOTA. This post explores the very fundamental algorithms that these advanced neural architectures were founded on. While we won’t get into the deep reinforcement learning just yet, we’ll see how it originated from Markov Decision Processes and Q-learning. We’ll discuss formulating our game as a Markov Decision Process and solving it directly through that approach. Then we’ll discuss the most foundational reinforcement learning algorithm: Q-learning.

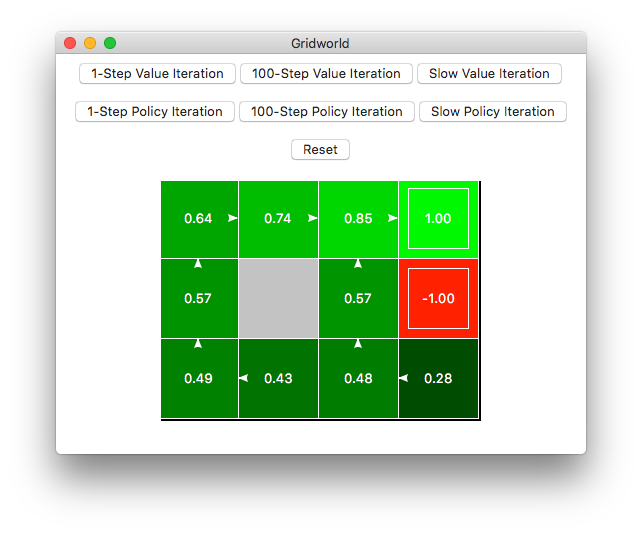

Let’s start by considering a really simple game as an example: GridWorld!

GridWorld is the classic reinforcement learning example. We have a robot in a discrete-space world whose goal is to recover the treasure while avoiding the fire pit. The light gray tiles are traversable by our robot while the dark gray tiles are regions where our robot cannot traverse.

Our robot can only move one tile at a time, but the motion is nondeterministic. In other words, if we tell our robot to move to the right, there is a high probability it will move to the right, but there is a nonzero probability it will move either up or down. This might seem like a strange addition to GridWorld, but this models real-world scenarios: telling our robot or agent to perform an action doesn’t necessarily mean it will perform that action perfectly.

Given this information about our GridWorld game, our goal is to come up with a policy for our environment that tells our robot which action to take based on where it is in the world to get to the treasure.

Markov Decision Processes (MDPs)

There are several techniques to solving our game, but we need to formalize our game into a Markov Decision Process (MDP) to use these methods. There are four components to an MDP:

- A set of all possible configurations of our game $S$ called the state space.

- A set of all possible actions our agent can take $A$ called the action space.

- A transition function $T(s,a,s’)$ that tells us the probability of being in state $s$, taking action $a$, and ending up in state $s’$.

- A reward function $R(s,a,s’)$ that tells us the reward of being in state $s$, taking action $a$, and ending up in state $s’$.

In addition to components, we also have two additional “practicality” components: terminal states and a discount parameter $\gamma\in[0,1]$. Terminal states are simply when the MDP or reinforcement learning task “ends”. If we were training an agent to play a game, then the terminal state would be the end of the game, e.g., checkmate. Additionally we have $\gamma$. This is called the discounting factor or discount. It’s a “hyperparameter” that allows us to express preference for receiving rewards sooner rather than later. For example, if $\gamma\approx 1$, then there’s no discounting and we prefer long-term rewards. But if $\gamma\approx 0$, then we heavily discount values and prefer rewards sooner. In practice, the discount helps our MDP-solving algorithms converge. For the rest of this post, we’ll set our discount to $\gamma=0.9$ as a hyperparameter. Our terminal states are recovering the treasure or falling into the fire pit.

In the context of our GridWorld game, $S$ is all possible configurations of our GridWorld, i.e., the position of our robot. $A$, our action space, is up, down, left, and right. For our purposes, let’s define the transition function like this: 80% of the time, our robot will take the correct action, but 10% of the time, our robot will move in another direction besides behind it. For example, if we tell our robot to move to the right, there’s a 80% chance it will do that, but there’s a 10% chance it will move up and a 10% chance it will move down. If we tell our robot to move up, there’s a 80% chance it will do that, but there’s a 10% chance it will move left and a 10% chance it will move right. This is just an arbitrary definition of the transition function to make the point that our actions for an MDP is nondeterministic.

The only requirement of our transition function is that it must make a true probability distribution over all of the states. Another interpretation of $T(s,a,s’)$ is that it maps state-action pairs $(s,a)$ to a new state $s’$. So all of the values of this function must sum to one. Mathematically, $\sum_{s’\in S}T(s,a,s’) = 1$ must be true. Our transition function follows this rule because all of the nonzero values sum to one:

\[\sum_{s'\in S}T(s,a,s') = \underbrace{0.8}_{\text{correct action}}+\underbrace{0.1+0.1}_{\text{incorrect actions}}=1\]Since our environment is restricted so that it is not possible to transition from any state to any other state, those values are just zero, i.e., we can only move one adjacent tile at a time, not teleport across the map.

Finally, our reward function is fairly simple: if we end up recovering the treasure, we get a reward of $+1$, and we get a reward of $-1$ if we land in the fire pit. (These values are arbitrary, though rewards are usually bound between $-1$ and $+1$ conventionally.) Based on how we defined our reward function, you may notice that we don’t really need it to be a function of $a$ or $s’$ since we’re only concerned with which state $s$ we’re currently in. In this case, we can reduce our reward function to just being a function of $s$: $R(s)$. We’ll make this reduction later on to help simplify equations.

Solving MDPs with Value Iteration

Now that we have a formal definition of our MDP, we want to solve for the optimal policy $\pi^{\ast}(s)$ that tell us which action to take in state $s$ to maximize our future expected reward. Value Iteration is one way we can figure out the optimal policy. For each state $s$, we compute the future expected reward of starting in state $s$ and acting optimally until the end of the MDP. We’ll call this value $V^{\ast}(s)$, and there’s one for each state. The reason we’re computing the expected value is because MDPs are nondeterministic.

We can compute $V^*(s)$ using the Bellman Equation:

\[V^*(s)=\max_a\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V^*(s')]\]The Bellman Equation seems like a huge mess (with a recursive definition!), but let’s dissect it to gain a better understanding of why this computes the future expected reward. First, let’s take a look at the quantity in the brackets:

\[\underbrace{R(s,a,s')}_{\substack{\text{immediate}\\\text{reward}}} + \underbrace{\gamma V^*(s')}_{\substack{\text{discounted future}\\\text{value}}}\]This quantity computes the total (discounted) reward of taking action $a$ in state $s$ and ending up in state $s’$ and then playing optimally starting at state $s’$. Notice this is a recursive function: it’s written in terms of itself. This seems a little confusing so I have a picture to explain it:

Don’t think too deep into the recursion! The bracketed quantity just breaks up the total reward into two parts: the immediate, right-now reward for taking action $a$ in state $s$ and ending up in state $s’$: $R(s,a,s’)$, and the discounted future reward $\gamma V^*(s’)$.

However, recall that our actions are probabilistic so taking action $a$ in state $s$ doesn’t guarantee we always end up in the same state. This is where the sum over $s’$ and transition function $T(s,a,s’)$ come in:

\[\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V^*(s')]\]This sum actually computes the expected value over all possible ending states $s’$! In other words, this is a weighted sum over all possible ending states $s’$ after starting in state $s$ and taking action $a$ of the total reward $R(s,a,s’) + \gamma V^*(s’)$ where the weights are the probabilities encoded in the transition function $T(s,a,s’)$!

Now let’s take a look at the entire thing:

\[\max_a\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V^*(s')]\]The only thing we’ve added is the max operation. This is because we only care about the action that maximizes the future expected reward. Hence, we compute the future expected reward for each possible action and take the maximum of those values because we would only ever select the action to maximize the future expected reward.

Let’s look at a concrete example.

Let’s compute $V^*(s)$. The best action is to go to the right so let’s only consider computing the expected value for that action; in other words, we only have to consider the future expected reward for $a=\texttt{right}$. For that action, 80% of the time, the robot will actually move to the right, and we can compute the future expected reward for ending up with the treasure:

\[T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V^*(s')] = 0.8(0 + 0.9 * 1) = 0.8(0.9) = 0.72\]$T(s,a,s’)=0.8$ because of the 80% chance our robot will actually move to the right.

$R(s,a,s’)=0$ because $s$ is not a terminal state.

$\gamma=0.9$ as a hyperparameter.

$V^*(s’)=+1$ from the map.

However, there’s also a 10% chance our robot will move down, and we can compute the future expected reward for that possibility too:

\[T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V^*(s')] = 0.1(0 + 0.9 * 0) = 0\]Summing these up, we get the following.

\[V^*(s)=0.72\](Our robot can’t move up since that is not a valid ending state since we would be outside of the map.) Now we repeat this process for all of the states. Notice that we’ll end up with many zero values because the values of each of the states are initialized to zero. But doing this process once isn’t enough. Consider the state to the left of the fire pit: since the state left of the treasure has been updated to a nonzero value, we can now update the state left of the fire pit. And when that state has a nonzero value, we can update the state under that one, and so on. It seems that we have to compute the values of all of the states over and over again until they stop changing drastically.

Hence, we recompute all of our values over and over again, iteratively, using dynamic programming. We use the iterative version of the Bellman Equation (where $k$ represents the iteration number):

\[V_{k+1}(s)=\max_a\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V_k(s')]\]And so we get our value iteration algorithm:

- Initialize $V_0(s) = 0$ for all states $s$

-

Compute new values for all states $s$

\[V_{k+1}(s)=\max_a\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V_k(s')]\] - Go to 2 until convergence

By “until convergence”, we mean that the values don’t change much. Practically speaking, we have a minimum delta parameter and if the difference between two iterations of the values is less than the minimum delta parameter, then we say value iteration has converged. The wonderful thing about value iteration is that the values converge to to the optimal values eventually, i.e., in a finite number of steps, regardless of the initial values! Mathematically, $V_k(s)=V^*(s)$ for a large $k$. In fact, there’s a mathematical proof behind this!

So after we run value iteration, we have an associated value for each state that represents the future expected reward, i.e., if we started in state $s$ and acted optimally, $V^*(s)$ is the expected reward we would received. Hence, values that are near “good” reward states will be larger than values that are farther away because the closer we are to a positive reward, the greater the likelihood that we’ll receive that reward if we act optimally.

So now that we have these values, we can use them to compute the optimal policy $\pi^*(s)$ for each state $s$ in a subsequent step called policy extraction. Suppose we’re at a state $s$, and we want to know which action to take to maximize our future expected reward. We can look at the values of the adjacent states, factoring in the transition function for nondeterminism, and pick the action that will most likely put us in a state with the largest adjacent value. Mathematically, we can compute the policy like this:

\[\DeclareMathOperator*{\argmax}{arg\,max} \pi^*(s)=\argmax_a \sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V^*(s')]\]Notice that this looks very similar to the Bellman Equation! We just swap out $\max$ for $\argmax$. This effectively does a one-step lookahead to see which action to take to maximize the future expected reward.

That solves for our optimal policy which we can give to our agent to execute! Here’s an image of running value iteration until convergence for our GridWorld example with the policy shown as arrows at each state:

Value iteration can be used to solve MDPs, but there are some issues with it: it’s slow and indirectly computes the policy. Computationally, value iteration takes $\mathcal{O}(S^2A)$ per iteration. One thing you may notice when using value iteration is that the policy often converges before the values do; the optimal policy might not change for a few hundred iterations while the values converge. The only reason we want the optimal values is so we can compute the optimal policy! This leads me to the second issue of value iteration: the values are indirectly used to compute the policy. After our value iteration converges, then we can compute the policy using the lookahead.

Solving MDPs with Policy Iteration

Instead of computing the values and then computing the policy, we can just directly manipulate the policy! This approach is called policy iteration. The algorithm is broken up into two steps: policy evaluation and policy improvement.

First, we choose an arbitrary policy $\pi$. We’ll be improving this policy as we go so it doesn’t matter what it is initialized to, e.g., always move to the right. Just like value iteration, policy iteration also converges to an optimal policy!

For policy evaluation, we fix the policy $\pi$ and compute values for the fixed policy!

- Initialize $V_0(s) = 0$ for all states $s$

-

Compute new values for all states $s$ given policy $\pi$

\[V_{k+1}(s)=\sum_{s'} T(s,\pi(s),s')[R(s,\pi(s),s') + \gamma V_k(s')]\] - Go to 2 until convergence

This looks very similar to value iteration! We removed the $\max_a$ and replaced $a$ with $\pi(s)$ because we use our fixed policy $\pi(s)$ to tell us which action to take! This step is faster than value iteration because we’re only considering one action $\pi(s)$, not all of them. These values tell us how good our current policy $\pi$ is. From this information, we can improve our policy!

For policy improvement, we use the values we computed before to update our policy.

-

Update policy

\[\pi(s)=\argmax_a \sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V^*(s')]\] -

Go to 1 until convergence

By “until convergence”, we mean that the policy doesn’t change. This is the same as the policy extraction step in value iteration, except we repeat this step multiple times. If the policy did change, then we go back to policy evaluation to see how good our new policy is. Only until our policy stops changing do we finish policy iteration.

Policy iteration has some issues too, namely the $\mathcal{O}(A^S)$ complexity for each iteration. Although the optimal policy converges much slower with value iteration in terms of number of iterations, policy iteration requires more time per iteration since it runs a smaller version of value iteration for each iteration.

Differences between value iteration and policy iteration

To recap, value iteration and policy iteration are both techniques used to solve MDPs and compute the optimal policy $\pi^*(s)$ given a complete MDP definition.

Value iteration is broken up into two steps: finding the optimal values (iterative) and policy extraction (one-time). With value iteration, we start with an arbitrary value function and iteratively find the optimal values. At each iteration, we refine the values and move them closer to the optimal ones. Each iteration takes $\mathcal{O}(S^2A)$. After we find the optimal values, we perform policy extraction once to compute our optimal policy from our optimal values.

Policy iteration is broken up into two steps: policy evaluation (iterative) and policy extraction (iterative). With policy iteration, we start with an arbitrary policy and iteratively improve it until it is the optimal policy. For policy evaluation, we fix our policy and compute the values for each state under that policy. Afterward, for policy improvement, we update the policy using a similar algorithm to policy extraction, except we check if the policy has converged or not, i.e., has the policy changed or not. If we have a changed policy, we go back to the policy evaluation step to see how good this new policy is and then we improve it. We keep doing this policy evaluation and improvement loop until the policy converges, i.e., doesn’t change. Each iteration takes $\mathcal{O}(A^S)$.

Which one is better? As satisfying as it may be to say “you should always use X because it’s the better algorithm!”, the correct answer to that question is the least satisfying answer: it depends on your problem! (From personal experience, I’ve found that policy iteration generally tends to converge a bit quicker than value iteration.)

When solving an MDP using either value or policy iteration, notice we don’t actually tell our agent to take any real actions in the environment. It’s just “thinking” about what would happen if it took those actions. We’re creating a plan from the complete information that we have. The agent doesn’t actually play the game or perform the task. Furthermore, in real-world tasks, we often don’t know which actions will lead to high rewards, i.e., the reward function, nor which states we’ll end up in after performing some action, i.e. the transition function.

For example, think about learning to play a new video game. Starting out, you don’t know which buttons or button combinations lead to more points nor what will happen to the game state. Nevertheless, many people play video games and get high scores all of the time. How do they do it? The key is they play the game over and over again to learn which actions tend to produce more points! This is the central idea behind reinforcement learning: playing the game!

Reinforcement Learning

Since we don’t know our reward or transition functions, we still need a way to compute the optimal policy, but this time, we have to play out the game or perform the task.

Model-based Learning

One thought might be to figure out the reward and transition functions by playing the game and tallying up the observations (and normalizing for the transition function).

For example, suppose we’re in a particular state $s$ and tell our agent to move to the right, and it does. Then, in the next game, we find ourselves back in $s$ and tell our robot to perform the same action, and it moves down instead. We keep track of whenever we are in state $s$, which action we perform, and which state we end up in. After playing 100 games, perhaps we find that 90 times, in state $s$, the robot actually moves like we expect it to, but 10 times, it did a 180 spin and moved in the opposite direction. We can normalize these tallies to come up with a model for our transition function: 90% of the time our robot moves in the correct direction, but 10% of the time, the robot moves in the opposite direction. We can take a similar approach to learning the reward function.

This approach is called a model-based approach or a model-based algorithm. By playing the game, we build models of our transition and reward functions. We play the game over and over again until our models of both functions converge, i.e., they stop changing drastically. Then, we can use value or policy iteration to compute our policy just like with MDPs!

Q-learning

As you might have inferred, if there are model-based algorithms, there are also model-free algorithms. These algorithms do not learn a model; instead, they derive the optimal policy directly, without explicitly learning the reward or transition functions.

The algorithm we’ll look at is called Q-learning, and it’s the basis for many deep reinforcement learning models. Let’s revisit value iteration briefly. One issue with value iteration was that we had to recover the optimal policy as a separate step because we took the max over all of the actions and max isn’t reversible/invertible. The idea behind Q-learning is to store the value for each action at each state. This is called a Q-value, i.e., a state-action pair. At each state, we store the future expected reward for each action. By using Q-values instead of just values, we can quickly and trivially recover the policy: in state $s$, we simply select the action with the largest Q-value!

\[\pi^*(s) = \argmax_a Q(s,a)\]But how do we compute these Q-values to begin with? The Q-learning algorithm is similar to the value iteration algorithm, except Q-learning is model-free.

- Initialize $Q(s,a)=0$ for all state-action pairs

- In state $s$, perform action $a=\pi^*(s)$, i.e., the optimal action, to end up in state $s’$ with some reward $r$ to get the tuple $(s, a, s’, r)$

-

Compute the new estimated Q-value

\[\hat{Q}(s,a) = r + \gamma~\underbrace{\max_{a'} Q_k(s', a')}_{\substack{\text{estimated optimal}\\\text{future value}}}\] -

Update the current Q-value by smoothing the new estimated and existing one

\[Q_{k+1}(s, a) = (1-\alpha)Q_k(s, a) + \alpha \hat{Q}(s, a)\] - Go to 2 until convergence

$\alpha$ is the learning rate, similar to what’s used for neural networks. In fact, notice that we can re-write Step 4 as a gradient descent update rule:

\[Q_{k+1}(s, a) = Q_k(s, a) + \alpha(\hat{Q}(s, a) - Q_k(s, a))\]Like value iteration, Q-learning also converges to the optimal values, and we can recover the optimal policy from these Q-values! Here is an example of Q-learning on our GridWorld environment with the policy highlighted:

There are some improvements on the base Q-learning algorithm that we can make to improve our agent’s performance. One issue that Q-learning suffers from is lack of exploration of the state-action space. In other words, when our agents finds a set of actions that leads to a high reward state, it will repeatedly follow that path. While this is what we want our agent to do, there’s always the chance that there exists an even higher reward path. So we have to balance the two: exploration vs. exploitation.

One way to encourage our agent to explore other possible states is called $\epsilon$-greedy exploration. During training, some small fraction of the time $\epsilon$, our agent will take a random action instead of the optimal action. We decay $\epsilon$ during the training process to transition from exploration to exploitation. The rationale behind this is that when our agent first starts in our world, it knows nothing about which actions to take; this is the ideal time to start exploring states. As the agent learns, it becomes more aware of which action sequence leads to high rewards; we don’t need to do as much exploration now since our agent knows more about the world.

Another improvement, taken from neural networks, is to decay the learning rate $\alpha$. This is also straightforward to do and helps our Q-values converge, just like it helps network weights converge for neural networks.

These two improvements can help our Q-learning algorithm converge to the optimal policy quicker.

Conclusion

Markov Decision Processes give us a way to formalize games and tasks that involve an agent and an environment. With an MDP, the goal is to find the optimal policy that tells our agent how to act in the environment to produce the maximum expected reward. We can solve for this policy using value iteration, figuring out the future expected reward at each state and computing the policy, or through policy iteration, directly modifying the policy until it converges. However, MDP make critical assumptions about the real world: we know how our agent will act given any action in any state and we know which actions lead to good rewards. Reinforcement learning, specifically Q-learning, discards these assumptions and computes the policy without directly knowing either of those things. Instead, we actually have our agent take actions in the environment and observe their outcome. From this, we can determine which actions lead to the maximum expected reward.

Q-learning is a fundamental algorithm that acts as the springboard for the deep reinforcement learning algorithms used to beat humans at Go and DOTA. While I didn’t cover deep reinforcement learning in this post (coming soon 🙂), having a good understanding Q-learning helps in understanding the modern reinforcement learning algorithms.

Appendix

Alternative Form of the Bellman Equation

There’s another, equivalent form of the original Bellman Equation that tends to be used more frequently:

\[V_{k+1}(s)=R(s) + \gamma\max_a\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')V_k(s')\]This simpler form runs a bit faster because we don’t have to compute the reward function for each action for each ending state. However, this does make the assumption that the reward function is only a function of the current state we’re in, which may or may not be a reasonable one to make. In our GridWorld case, we only receive a reward when we either reach the treasure or fall into the fire pit. Hence, we only care about our current state so we could have used this update equation instead of the full Bellman Equation.

We can reduce the Bellman Equation down to this simplified one as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} V_{k+1}(s)&=\max_a\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')[R(s,a,s') + \gamma V_k(s')]\\ &=\max_a\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')[R(s) + \gamma V_k(s')]\\ &=\max_a\{\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')R(s) + \sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')\cdot\gamma V_k(s')\}\\ &=\max_a\{R(s)\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s') + \gamma\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')V_k(s')\}\\ &=\max_a\{R(s) + \gamma\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')V_k(s')\}\\ &=R(s) + \max_a\gamma\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')V_k(s')\\ V_{k+1}(s)&=R(s) + \gamma\max_a\sum_{s'} T(s,a,s')V_k(s') \end{aligned}\]There are a few points to note here. $\sum_{s’} T(s,a,s’)=1$ because our transition function is a probability distribution over all possible ending states by taking action $a$ in state $s$. Also, since $R(s)$ is not a function of actions anymore, we can reduce $\max$ to operate only on $\sum_{s’} T(s,a,s’)V_k(s’)$ rather than $R(s) + \gamma\sum_{s’} T(s,a,s’)V_k(s’)$. Finally $\gamma$ is just a constant so we can pull it out of the $\max$ operation.